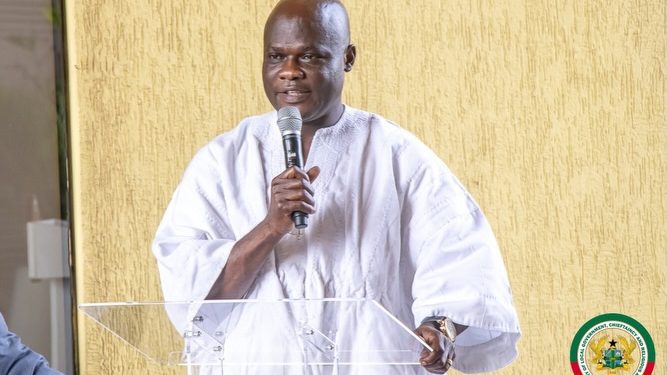

Journalist Leads Crusade Against Youth Drug and Alcohol Abuse in Schools

In an intensified effort to curb rampant substance abuse among young people, multiple award-winning journalist Mr. Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen has shifted his media campaign to school grounds. His latest stop: Bolgatanga Senior High School (BIGBOSS), where he engaged students on the dire dangers and shattered futures linked to drugs and alcohol. His journey to this podium had begun not in a newsroom, but in the shadows. It had started with a camera lens pointed into places most avert their eyes from: the ghettos. His recent documentary, bearing the grim title “Swallowed by Drugs,” was not just a piece of work; it was a testament to a deepening nightmare. The footage he captured in various ghettos was a brutal, unvarnished portrait of a generation in peril. Young men and women, some barely older than the students now before him, lost in a haze of illicit smoke and cheap alcohol, their eyes hollow, their potential leaching away into the dirt floors of derelict shacks. Watch the full documentary: He had spoken to them, these ghosts of what could have been. Their stories were a broken record of tragedy. “I started in school,” one whispered, his voice thin as paper. “My friends said it would make me feel good, make me forget my problems.” Another, shivering slightly, confessed, “It is part of me now. I cannot stop. My family, they don’t know me anymore.” Many had abandoned their education, their homes, their very identities, seduced and then enslaved by substances that promised escape but delivered only a cage. These were not faceless statistics to Ngamegbulam. They were individuals whose dreams had names: the boy who wanted to be an engineer, the girl who once aced her science exams, the aspiring footballer with lightning in his feet. Their dreams, as he would soon tell the listening students, were now “shaky.” A gentle word for a brutal truth: they were dying. Witnessing this collapse firsthand had transformed Ngamegbulam’s role from documentarian to crusader. If he could expose the problem, he reasoned, he must also try to stem the tide. And so, he had intensified his media campaign, turning his focus upstream, to the schools, to the places where the slide often begins, to the students still perched on the precipice of choice. BIGBOSS was one such stop. “If you care to know,” his voice, calm yet urgent, broke the hall’s quiet. “If you care to know, over 400 million people live with the use of alcohol disorder. Yearly, 3 million people die as a result.” He let the global scale of the tragedy hang in the air before bringing it home, sharply, painfully local. “In Ghana, over 50,000 people find themselves in this abuse. Out of that 50,000, 35,000 are students. Just like you. Thirty-five thousand.” A subtle ripple went through the crowd. The number was no longer an abstract global figure; it was a potential classmate, a friend on the next bench, a reflection in the mirror. The remaining thousands, he noted, were “our mothers and our fathers.” But the youth, the JHS and SHS students, bore the brunt. “That means these people we are talking about,” he continued, leaning into the mic, “their dream of becoming that doctor is shaky. Their dream of becoming a nurse is shaky.” He spoke not with the fire of condemnation, but with the empathy of a witness and the clarity of a guide. He dismantled the false allure of alcohol and drugs brick by brick. It was not just a health issue, he explained; it was a future-annihilator. “Through studies, now and then, it’s just a way to improve yourself. It’s a way to help your family, your society, and your country. But when you engage yourself in alcohol, you will see that those dreams will never come true.” Then, he pivoted to aspiration. He gestured beyond the school walls, towards the seats of power and influence. “You admire those in Parliament. Our MPs. You love what they do, don’t you? And you want to be like them, don’t you?” Heads nodded, almost imperceptibly. “So, how do you think you will be like those people when you engage in drinking alcohol and taking drugs? You cannot be like them.” His alternative was simple, powerful, and rooted in self-interest. “The only way we can be like them is by shying away from alcohol and drug abuse. That is the only way you can represent your community in Parliament. That is the way you can be the Speaker. That is the way you can become a minister. That is the way you can also become a president.” He was not there to lecture, he insisted. He was a messenger, delivering a warning they must carry within themselves. “I am here to actually pass this message to you so that as you are going about your duties… You should know that drug and alcohol abuse is one thing that can actually deny you your dream.” His plea became personal, communal. He asked them to remember this gathering when they returned to their homes and communities, where social gatherings often orbit around “drinks and some other goodies.” He pointed to the worrying trend in the region: “Sports [drinking spots] are becoming the order of the day… The more people patronize all these drinking spots, the more people are going to waste every day.” Then, he gave them a charge, a title to wear with pride. “I want you to be an ambassador in your community. An ambassador in your constituency. You should be in that position of also advising members of your community… because it will never help the society to grow.” He concluded with a humility that resonated deeply. He respected their time, their studies, and their busy lives. But he needed one thing from them before he left. A collective declaration. A line in the sand. “Please, you have to say, ‘Say no to drug and alcohol abuse.’ I want you to say that.” For a heartbeat, there

The Broken Chalkboards: The Upper East Regional Education Director’s Battle Against Student Riots and Indiscipline in Schools

What once were sanctuaries of learning and personal growth have, in recent times, become epicenters of chaos and disruption. The phenomenon of student riots, once rare, now threatens to become a troubling ritual, a recurring storm that leaves behind fractured trust, shattered chalkboards, and an environment far removed from the ideals of education. Razak Z. Abdul-Korah, the Upper East Regional Education Director, has never shied away from confronting uncomfortable truths. In a recent documentary, “The Broken Chalkboards,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of Apexnewsgh, Mr. Abdul-Korah spoke candidly about the growing tide of student unrest and painted a comprehensive picture of its causes, impacts, and the necessary path forward. For decades, the schools of the Upper East Region have been pillars of hope—places where young minds are shaped for the future. But lately, a disquieting trend has emerged. Riots, demonstrations, and acts of indiscipline are no longer isolated incidents. They are spreading, springing up across almost all institutions, threatening the peace and stability necessary for effective learning. “It is of concern to everybody in the education space, all stakeholders as well,” Mr. Abdul-Korah began, his tone both measured and urgent. “A peaceful environment should be a creation of almost all stakeholders. So if one stakeholder happens not to be in line, it affects all.” Kindly watch the full video here: https://youtu.be/GSQR3-T6EaE. In his view, the responsibility to maintain peace cannot rest on one group alone. It must be a collective effort; school management, teachers, students, parents, and the wider community all have crucial roles to play. When even a single element falls out of harmony, the entire system feels the strain. Indiscipline, Mr. Abdul-Korah clarified, is not just a problem among students. “Let me even put it, not necessarily only student indiscipline, but indiscipline among staff, indiscipline among students, every level of indiscipline affects the management of the school.” While the recent spate of riots has spotlighted student behavior, the Regional Director was quick to point out that issues of discipline, or the lack thereof, cut across all levels. Sometimes, even administrative offices are not immune, though the manifestations may be less visible. “One trigger leads to another,” he explained. “It is not the best, especially when it goes out into demonstrations.” When discipline breaks down, the cost is not just measured in damaged property or lost learning hours, but in the erosion of trust and the peaceful environment schools strive to maintain. The cost of a riot is profound and far-reaching. “When students revolt against staff, there is mistrust. We are human beings. You may react, but as you go along, it may come in a different form to affect the learners,” Mr. Abdul-Korah stated. Every incident chips away at the fragile bond between teachers and students. Fear and suspicion replace mutual respect, and it can take months, sometimes years, for schools to regain their equilibrium. Learning outcomes suffer, and the ultimate victims are the students themselves. Specific cases, like the disturbances in Gowrie, Bongo, and Zuarungu, were cited. In Gworie, the environment became so inhospitable that learning was all but halted. In Bongo, a single expression of displeasure threatened to spiral out of control. In Zuarungu, the incident’s outcome remains unresolved, hanging over the school community like a specter. Despite the challenges, Mr. Abdul-Korah remains resolute. “We should work to see how to address some of them,” he insisted. Reports are being compiled and sent to the Director General for study and advice. Meanwhile, efforts are underway at the regional level to address concerns as they arise. “Every single actor that can contribute to creating this enabling environment should not be left out.” At every forum, whether with school managers, student bodies, or community elders, the message is the same: peace and discipline are everyone’s responsibility. According to the Regional Director, transparency is key. When the monitoring team visits a school, their first point of contact is the headteacher, ensuring that the purpose of their visit is clear. This openness extends to student forums, where students are encouraged to voice their concerns and see themselves as part of the management process. Many students, Mr. Abdul-Korah observed, do not realize that they are part of the disciplinary and management structures. “If a student is to be disciplined, the student leadership is part of the disciplinary committee. So you are aware, and that is how you are part of the management.” By making student leaders active participants in school management, a sense of ownership and responsibility is fostered. Issues can be raised and resolved through proper channels, reducing the likelihood of escalation. Speaking about effective communication of decisions, the Regional Director pointed out, misunderstandings often arise when decisions, especially disciplinary ones, are not communicated effectively. In one case at Zamse, a student was disciplined, but the reasons were not relayed to the rest of the students, leading to protests. In reality, the action had been recommended by fellow students who felt threatened by their peer’s behavior. “If we’re doing all these things to bring people on board in the management practice, we will reduce the tension,” the Director emphasized. According to Mr. Abdul-Korah, “Once tension is down, you may not see some of these things happening.” By fostering dialogue and quelling rumors, the triggers for riots can be addressed before they explode into full-blown crises. The Director was particularly keen to highlight the role of school management. “The best leader, the best manager certainly has some leadership qualities that drive the activities in his office.” But even the best leaders make mistakes. When they do, the ability to admit fault and correct course is essential. “It’s not everything that as a leader you get 100% right. But as and when, you could do take a decision without taking into consideration the consequences of it.” Sometimes, a careless remark or poorly thought-out decision can spark unrest. School boards and oversight bodies have a critical role to play in reducing tension. But the most effective interventions, Abdul-Korah believes, happen at the

The Broken Chalkboards: Rev. Abukari Thomas Calls for Collective Action and Moral Reform Amid Rising Student Riots in Upper East Region

In recent years, the Upper East Region has witnessed a troubling surge in student riots across its educational institutions. This trend has left educators, parents, and leaders grappling for answers. Among those raising their voices for change is Rev. Abukari Thomas, Chairman of the Upper East Regional Christian Council, Bolgatanga and a respected Baptist Church head Pastor, who shared his profound reflections in a documentary “Broken Chalkboards” produced by journalist Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of Apexnewsgh. Rev. Abukari’s insights are a clarion call to society, urging all stakeholders to acknowledge the gravity of campus unrest and to seek solutions rooted in empathy, communication, and moral guidance. His message is not one of blame, but of collective responsibility, a rallying cry to educators, parents, religious leaders, and students themselves to reclaim the original purpose of education and to restore dignity and order in schools. Addressing the matter, Rev. Abukari begins with an earnest appeal: “I come your way to add my voice to things that are happening in our society, which are heartbreaking. For example, we look at our various institutions, we see some emerging trends that are of late not the best for u,s and it would not be appropriate for us to be silent on this issue.” Kindly watch the full video here: https://youtu.be/GSQR3-T6EaE. He observes with concern that nearly 90% of secondary schools in the Upper East have experienced some form of student unrest, a situation unprecedented in recent history. Rather than apportioning blame, he emphasizes the need for unity and shared purpose in seeking solutions. “We all have to find ourselves in getting a solution to this. So my focus here is not to look at who is at fault, but what can be done because we are in the woods and we need to come out.” Rev. Abukari laments the loss of the original vision for schools: environments meant to model, transform, and equip future leaders. He notes, “In our schools, this is a place where people are to be modelled, transformed, equipped, and then they will pick up leadership positions in the near future. But if we see them going all around destroying school properties…it might be a simple misunderstanding, misinformation or miscommunication.” The generational gap, he asserts, has made communication more complex. Today’s students are “sensitive and active,” with access to social media and peer influences sometimes leading them astray. Many, he warns, are unaware of the long-term consequences of their actions, including the destruction of scarce infrastructure. “The government has spent huge sums of amounts of money to put up infrastructure which our region is lacking. There is no institution in our region that we can boast and say that they have enough infrastructure…Why do we then destroy the few?” Rev. Abukari calls for proactive communication between school leadership and students, particularly through student representative councils. He suggests regular engagement, transparency about school management, and education about the realities of funding and resource allocation. “If students know that this is the right channel we are to pass through to get our grievances met, some of these instances we are observing will not be there.” He advocates for empowering student leaders with knowledge about their rights and responsibilities, as well as the costs involved in running a school. “If we explain, they will understand,” he says, reinforcing the need for dialogue over destruction. While acknowledging the importance of child rights, Rev. Abukari cautions that many students misunderstand where their rights begin and end. “You have the right to be educated, so if you have the right to be educated, it means you have the right to be trained and be corrected.” He recommends that corrective measures be made pragmatic and transparent, so that students understand the intention is reform, not punishment. “School authorities, can we let them get to this understanding?” he asks, adding that many students come from troubled homes and need more structured support in school. A critical gap, according to Rev. Abukari, is the lack of effective guidance and counseling offices in schools. He urges management to invest in these services, so students can seek help and receive warm, professional advice. “If we get guidance and counselors to take care, an open office where the students can walk in with their heartfelt issues and walk out warmly received and properly educated, most of these issues that we encounter in our institutions will not be there.” He also proposes the creation of robust reward systems to motivate positive behaviour, complementing disciplinary action. “If we see more awards given to well-disciplined, well-dressed, well-behaved students…I think it will motivate and encourage the students to tow this line.” As a religious leader, Rev. Abukari stresses the role of faith communities in shaping student character. He calls for stronger religious life on campus, with chaplains and imams working together to help students discover purpose and resist negative peer pressure. “Nobody’s destiny is promoted through rioting. Nobody’s destiny is promoted through bad behavior.” Religious institutions, he believes, must step up to provide moral guidance, especially for students from broken homes. “If we religious leaders make sure that we model their religious life in these institutions, I think definitely…the numbers [of riots] should reduce.” Rev. Abukari does not leave out parents and alumni, urging Parent-Teacher Associations and school boards to support rightful discipline and set positive examples. He warns against interventions that undermine necessary corrective measures, noting that “since he did it and went scot-free, there’s nothing wrong.” He encourages alumni to take pride in building their schools, not destroying them: “It’s for us to go through our books, study, come out with flying colors, move to the next level so that you come back one day and say yes, I was a product of this institution.” A sobering reminder is offered to students: school records, including involvement in riots, often follow individuals throughout their lives. “If they pull out the files and you were part of those who burned down the dormitory, you were the gang leader,

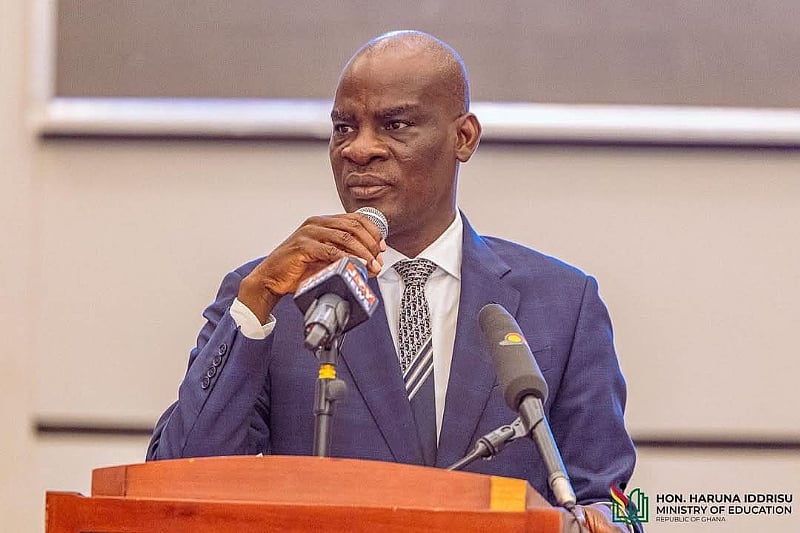

Education Minister Reaffirms Biological Definition of Sex in School Materials Amid Ongoing Debate

In the wake of growing public debate about the content of teaching and learning materials in Ghana, Minister of Education Haruna Iddrisu has issued a firm clarification: all references to sex in the nation’s educational resources must strictly adhere to biological definitions based on birth. The Minister made his position clear during a training session in Tamale focused on the Ghanaian Youth Handbook and the implementation of the Guidance and Counselling framework. Mr. Iddrisu emphasized that, going forward, any mention of a man, a woman, or sex in classroom literature must be grounded solely in biology, reflecting Ghanaian values, culture, and social norms. He explained that this directive was issued after concerns arose about ambiguous content in certain educational materials, and confirmed that such issues have since been addressed and corrected. The Minister further instructed the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NaCCA) to take responsibility for the controversy and to act swiftly. He revealed that NaCCA had admitted to inconsistencies in the definition of gender identity within the Year Two Physical Education and Health elective teacher manual for senior high schools—a manual that has now been recalled in all 736 printed copies. Corrections have already been made to the online curriculum, and teachers have been advised not to use outdated hard copies. Haruna Iddrisu also noted that the curriculum remains dynamic, with regular updates made available online to ensure all educators have access to the latest approved standards. “The moral foundation of our society depends on upholding these values through our education system,” he remarked, underscoring the importance of cultural alignment in teaching. His statements come at a time of heightened political tension, as the Minority in Parliament continues to call for the removal of NaCCA’s leadership over what they describe as gross negligence. In response, NaCCA has not only withdrawn the affected manuals but also released a revised edition that, according to officials, aligns with Ghanaian cultural norms and provides a biological perspective on the topic. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

Inmates May Earn Reduced Sentences Under New Prison Education and Production Scheme

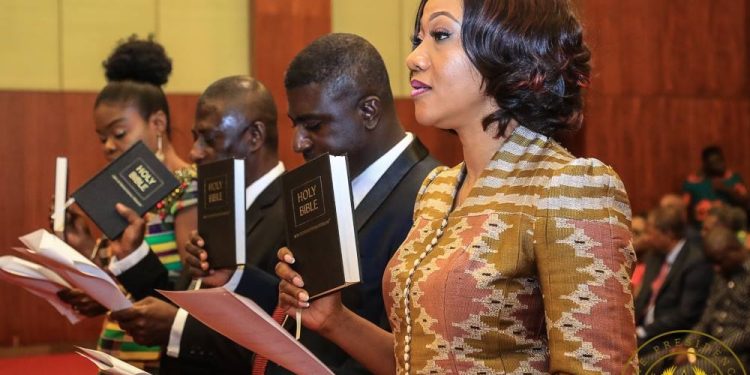

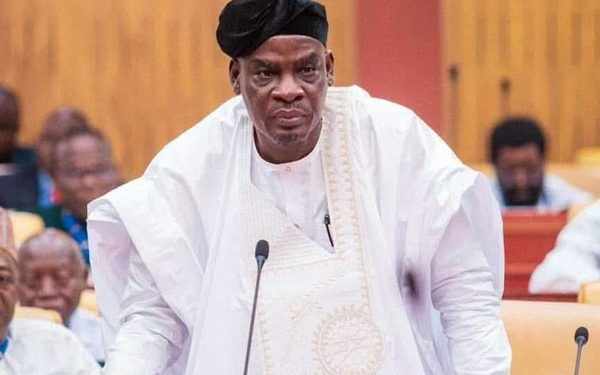

A wave of optimism swept through Ghana’s prison system following the Ministry of the Interior’s announcement of a new initiative that connects good behaviour with opportunities for sentence reduction. The scheme, unveiled by Minister of the Interior Mohammed Muntaka Mubarak, aims to transform the nation’s correctional facilities into hubs for rehabilitation, skill-building, and productive work. At a ceremonial signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Ministry of Education on January 14, 2026, Minister Mubarak outlined how the program will allow inmates to participate in the manufacturing of essential goods for public schools. Under the initiative, prisoners will produce school furniture, uniforms, and sanitary pads, directly supporting local education while acquiring practical skills for reintegration into society. Integral to the project’s design is the promise of sentence reduction for well-behaved inmates. Minister Mubarak explained that under the proposed Community Service Bill, now before Parliament, inmates who diligently participate in prison industries for a year may see their sentences shortened by three months. “So, instead of doing one year, you will do nine months,” he stated, emphasizing the reformative spirit behind the program. The government hopes this pioneering approach will encourage positive behaviour, equip inmates with valuable skills, and contribute to national development, all while offering a new path to justice and rehabilitation in Ghana’s correctional system.

Minority in Parliament Calls for Dismissal of NaCCA Leadership Over LGBTQ Content Controversy

A political storm erupted in Parliament as the Minority caucus demanded the immediate dismissal of Professor Samuel Ofori Bekoe, Director-General of the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NaCCA), and the Council’s Board Chair. The Minority accused NaCCA’s leadership of gross negligence following the inclusion of LGBTQ-related content in a Physical Education teacher manual, which has since been withdrawn. The controversy gained momentum after the Member of Parliament for Assin South, Rev. John Ntim Fordjour, alleged that the government was promoting an LGBTQ agenda through school materials. In response, NaCCA swiftly withdrew the printed Senior High School (SHS) teacher manual, acknowledging that sections on “Gender Identity” in the Year Two Physical Education and Health (Elective) Teacher Manual conflicted with Ghanaian cultural values and norms. NaCCA has since released a revised edition of the manual, assuring the public that the updated version aligns with national values and offers a strictly biological perspective on the subject. Speaking to the press on Thursday, January 15, the Member of Parliament for Old Tafo, Vincent Ekow Assafuah, emphasized that NaCCA’s leadership failed to prevent the contentious content, calling it a serious breach of public trust. He further highlighted that the process of printing, distributing, and recalling the manuals resulted in financial losses for the state, losses for which NaCCA’s leadership should be held accountable. “We demand the dismissal of the Director-General of NaCCA and the Chairman of the Board for failure of oversight and breach of public trust. NaCCA is now telling us, assuming without admitting, that the document was developed by the NPP government in 2024. If you don’t believe in it, why go ahead to even print them in 2025? That is causing financial loss to the state because these are manuals you have printed and distributed across the country,” Assafuah stated. With the revised manual now in circulation, the controversy continues to spark heated debate across the political spectrum, with many watching closely to see how the government will respond to the Minority’s demands. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

The Broken Chalkboards: Nyeya Yen Calls for Better Food, Discipline, and Democratic School Management

Social justice advocate Nyeya Yen has shared deep concerns over the increasing rate of student riots in schools across the Upper East Region. Speaking in a documentary engagement with Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of Apexnewsgh in his recent documentary titled “The Broken Chalkboards”, Mr. Yen drew from both his experiences in Ghana and over 30 years of living in the United Kingdom to offer insights and solutions. He began by challenging the notion that Western countries, particularly the UK, offer a flawless model of education and discipline. “People tend to have an exaggerated opinion of the United Kingdom. But it is not a perfect society. It has also failed a lot of its young people, particularly in the black community.” Mr. Yen explained that while Ghana struggles with student unrest, British schools face equally troubling issues such as gang violence, substance abuse, and high dropout rates among black students. “There was a time in London when almost every week two or three children died, killed by other children. Many of them were black kids from inner-city communities who had no supervision at home.” Kindly watch the full video here: https://youtu.be/GSQR3-T6EaE. Turning back to Ghana, Mr. Yen argued that the root causes of school riots are often practical, with poor food quality topping the list. “One of the major reasons for school riots is extremely poor food. When children are given food that is not sufficient, they get organized. Many riots have occurred because of poor food.” He pointed to corruption in food distribution and low salaries of kitchen staff as aggravating factors. “Sometimes the school may be given 100 bags, but the authorities decide to keep 20. And by the time the food gets to the kitchen, the cooks, who are paid 600 or 1000 cedis, also take some home. In the end, the children suffer.” Beyond food, Yen stressed the importance of inclusive school management and student participation in decision-making. “Schools should be run democratically. Get students involved through councils. Even in simple things like the kitchen, discuss with them. Don’t just say, ‘I am in charge.’ That brings resentment, and resentment can lead to riots.” He also highlighted the role of peer influence, bullying, and substance misuse in fueling unrest. Citing the Zuarungu case linked to the Bawku conflict, he warned against ethnic divisions infiltrating schools. “My advice to the young people is that we are all Ghanaians. We shouldn’t say, I am Frafra, I am Kusasi, I am Dagomba. Hate is extremely bad, and students should not allow it to divide them.” On discipline, Mr. Yen clarified that it should not be equated with corporal punishment but with firm, consistent guidance. “Discipline is not about beating. It is about how you relate to the child. If you say you will withdraw a privilege, follow through. Children know when you are not serious, and they will take liberties.” He concluded by calling for better supervision, stronger discipline, fair treatment, and meaningful engagement of students as the way forward. “Some of these students are already 17 or 18, and they are adults, voting age. They should be involved in the running of schools. Only then can we prevent resentment from turning into riots.” Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

The Broken Chalkboards: Prof. David Millar Reveals 7 Root Causes of Student Riots and Pathways to Reform

The air, once filled with the hopeful banter of students, now trembles with the aftershocks of unrest. In the corridors of academia, concern ripples among parents and educators alike. Professor David Millar, President of the Millar Institute for Transdisciplinary and Development Studies, has added his voice in the documentary “The Broken Chalkboards,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of Apexnewsgh, as he warns: if the current wave of student riots is not checked, it threatens to engulf the entire nation. Kindly watch the full video here: https://youtu.be/GSQR3-T6EaE. Professor Millar’s observations are not mere conjecture. He describes, with painstaking clarity, how riots in secondary schools, once sporadic and exceptional, are becoming alarmingly routine. “It’s becoming very common and noticeable that rioting in schools, especially second-cycle institutions, is on the ascendancy. It’s beginning to increase nationwide,” he asserts. With each passing term, the risk grows that isolated incidents will ignite a conflagration, one that could destabilize the nation’s educational system and erode the social fabric. To understand the roots of this unrest, Professor Millar embarks on a thorough diagnosis of the contemporary school environment. His analysis yields seven interlocking factors, four major and cross-cutting, and three institution-specific, that fuel the flames of student discontent. The Shadow of Drug Abuse Foremost among the major factors is the specter of drug abuse and misuse. According to Prof. Millar, this problem is no longer confined to the school compound. It follows students home, forms habits, and then returns to infiltrate the school environment anew. The result is a culture where substance abuse becomes normalized, blurring the boundaries between personal recreation and institutional disruption. “We have to do something with drug abuse and drug misuse,” Prof. Millar insists, underscoring its centrality to the crisis. The Pressure Cooker of Peer Influence The second factor is the relentless pressure exerted by peer groups. Within the closed ecosystem of a school, peer validation becomes a form of currency. Membership in social circles is governed by overt and covert rules, and the need to belong can drive students to conform to destructive behaviors. For girls as well as boys, these peer groups can be both a refuge and a crucible—incubating actions that undermine the school’s integrity. The Rise of Cults and Weaponization Peer pressure, left unchecked, can metastasize into something even more insidious: the rise of cults within schools. These groups, often shrouded in secrecy and governed by their own codes, demand allegiance through symbolic acts, sometimes even the bearing of weapons. Inter-cult rivalries and competitions for dominance further stoke the fires of unrest. The existence of such groups, Prof. Millar warns, “weaponizes” peer relationships and transforms schools into battlegrounds. The Double-Edged Sword of Technology Modern information and communication technology (ICT) is another factor reshaping the school environment. Smartphones, social media, and even artificial intelligence platforms expose students to a world far beyond the classroom. While this can be a force for good, it also creates new avenues for comparison, competition, and subversion. Students return from holidays eager to display their new digital prowess, sometimes in ways that challenge or undermine school authority. The result is a generation increasingly at odds with the structures meant to guide them. Beyond these core issues, Prof. Millar identifies three more factors that vary from school to school. School Management Systems and Institutional Culture The management style of a school can either mitigate or exacerbate unrest. Institutions with strong religious affiliations or private ownership tend to be more responsive to misconduct, swiftly meting out discipline. Public schools, by contrast, often suffer from bureaucratic inertia—disciplinary procedures are drawn out, diluted by committees, and susceptible to outside interference. This laxity, combined with unclear institutional cultures, leaves a vacuum that disruptive elements are quick to fill. The Disruption Subculture A subtler, but no less significant, factor is what Prof. Millar calls the “subculture of disruption.” Weak students, fearful of looming examinations or unprepared for academic challenges, may seek to derail the school calendar altogether. By fomenting unrest, they hope to avoid failure and mask their own deficiencies. This phenomenon is often most acute as exams approach, with mass participation by those who feel threatened by strict enforcement of academic standards. The Parental Paradox Finally, the role of parents is both pivotal and paradoxical. While parental engagement is essential for effective discipline, unchecked indulgence can have the opposite effect. Some parents provide their children with cars, excessive pocket money, and privileges that enable misbehavior. At home, such actions may go unchecked; at school, they find eager collaborators among peer groups. The result is a feedback loop where home and school reinforce rather than correct negative behavior. While the destruction of property during riots is costly, Prof. Millar is more disturbed by the long-term impact on behaviors and attitudes. “It’s not so much the destruction of property… but the negative impact on behaviors and attitudes that are long-term. For me, that is the worrying part. Because these have long-term implications. We call them our future leaders. Imagine our future leaders coming out with all those vices. What sort of leadership do we get?” Having laid bare the roots of the crisis, Prof. Millar turns to solutions. His proposals are pragmatic, grounded in both research and years of experience. Conscientization and Civic Education The first step, he argues, is a renewed emphasis on civic education—what he calls “conscientization.” Many students, he notes, are simply unaware of the long-term consequences of their actions. By bringing in resource persons, former addicts, and career professionals to share their experiences, schools can equip students with the knowledge they need to avoid destructive pathways. “Educate, educate, re-educate,” Prof. Millar urges, advocating for a revival of civic education programs and the involvement of the National Commission for Civic Education in a large-scale, school-to-school campaign. Revitalizing School Life with Positive Engagement Prof. Millar also calls for a renaissance in extracurricular activities. In the past, debates, drama clubs, and cultural associations provided outlets for energy and creativity. Today, these activities hold less allure, leaving students idle and susceptible

Free Special Needs Education Announced for 2026

Excitement and hope filled the air at the grand opening of the Gloria Boatema Dadey–Nifa Basic School in Adukrom, as the Minister of Education, Haruna Iddrisu, delivered a landmark announcement for learners across Ghana. Addressing a crowd of educators, parents, and community leaders, Mr. Iddrisu declared that, from 2026 onwards, education for students with special needs would be completely free of charge. The minister explained that the initiative, set to commence under the leadership of President John Dramani Mahama, would be fully funded by the Ghana Education Trust Fund (GETFund). This bold move, he said, aims to lift the financial burden from families and ensure that every child, regardless of ability, has access to quality education. “I’m proud to announce that learning for special needs education in Ghana will be free and adequately funded by GETFund starting this year, 2026,” he proclaimed. Backing up this commitment, Mr. Iddrisu revealed that GETFund has allocated GH¢100 million in its 2026 budget specifically to strengthen special education nationwide. The funding will be used to procure essential teaching aids and assistive technology, ensuring that learners with special needs receive the support and resources vital to their development. The minister also took the opportunity to underscore a broader vision for Ghana’s education system. He stressed the importance of investing in basic education, arguing that early learning lays the foundation for lifelong success. Citing a popular adage about the power of formative years, Mr. Iddrisu reaffirmed President Mahama’s resolve to boost foundational learning and improve outcomes at the basic school level. With these promises and resources on the horizon, Ghana’s special needs students and their families can look forward to a more inclusive and supportive educational future. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

President Mahama Pledges Unbreakable Progress in Second Term

President John Dramani Mahama has begun his second term with a bold declaration: this time, the changes he brings to Ghana will be both profound and enduring. Returning to the presidency after an eight-year hiatus, President Mahama used the stage of the annual New Year School Conference on Tuesday, January 6, to outline his vision for a legacy of irreversible reforms. Addressing participants, he shared his resolve to elevate both the economy and governance systems to new heights. “I have decided to make this second mandate so graciously granted to me by Ghanaians count. I have pledged to raise our economy and governance to a level that no succeeding government can reverse,” he affirmed, signaling a new era of reform. President Mahama drew attention to the broader context of democratic backsliding in the region, stressing the need for Ghana to stand as a beacon of democratic resilience. “In a region where democracy is backsliding, we must demonstrate that democracy works and that our people can have faith in their leaders to uphold their interests and create opportunities for national prosperity,” he said. Reassuring the nation, President Mahama promised to uphold fiscal discipline and prudent economic management, vowing that such standards would not be compromised, even as the country approaches the 2028 election year. His commitment sets the tone for a second term dedicated to progress that cannot easily be undone, no matter who holds office next. Source: Apexnewsgh.com