Tragedy at El-Wak: Military Recruitment Stampede Claims 6 Lives in Accra

What began as a day of hope ended in heartbreak at the El-Wak Sports Stadium in Accra on Wednesday, November 12, 2025. The stadium, usually abuzz with the excitement of sporting events, became the scene of tragedy during an ongoing military recruitment exercise, as a stampede claimed the lives of 6 young Ghanaians and left several others critically injured. Trouble began early in the day, as thousands of hopeful applicants surged toward the stadium’s gates, desperate for a chance to enlist in the Ghana Armed Forces (GAF), the crowd, far larger than anticipated, quickly overwhelmed security personnel. Jostling and shoving at narrow entry points soon erupted into chaos. Within minutes, the festive atmosphere gave way to panic, screams, and a frantic struggle for safety. By evening, the military confirmed that six people had died, but the death toll later rose to 6 as six more succumbed to their injuries. The bodies of the deceased were transported to the 37 Military Hospital morgue, while dozens of others, some in critical condition, were rushed to the emergency ward and Intensive Care Unit. Security forces moved swiftly to cordon off the stadium and block all major access roads, allowing rescue teams to work unimpeded. The tragic stampede occurred amidst an extended recruitment period for the Ghana Armed Forces. Originally set to close on October 31, 2025, the deadline had been extended by a week to accommodate applicants who had faced technical issues with the online portal. The extension, announced in a statement signed by Colonel Evelyn Ntiamoah Asamoah, Acting Director General of Public Relations, was intended to ensure fairness, but instead contributed to the overwhelming turnout that fateful morning. As news of the tragedy spread, questions mounted about crowd control and safety measures at large-scale recruitment events. Authorities have yet to issue a full statement on the incident, but preliminary reports suggest that inadequate crowd management and the sheer number of applicants played a significant role in the disaster. Investigations are expected to be launched to uncover the precise circumstances that led to the stampede and to prevent similar tragedies in future recruitment exercises. For now, the nation mourns the loss of twelve of its youth, victims of a system overwhelmed by demand, and of hopes that, for some, ended in heartbreak rather than a new beginning. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

UER: 7,549 People Living With HIV Amid Rising New Infections

At the inauguration of the Upper East Regional Committee of the Ghana AIDS Commission (ReCCOM), Mr. Donatus Akamugri Atanga, the Upper East Regional Minister, shared sobering news with the gathering. The region, he revealed, is home to 7,549 people living with HIV. Of these, 345 are new infections, which translates to a regional prevalence rate of 0.85%. But the numbers held a deeper concern. Shockingly, only 49.4% of those affected are currently receiving lifesaving antiretroviral therapy. “These numbers reveal a significant gap that we must urgently address if we are to reach our targets and end AIDS as a public health concern by 2030,” the Minister urged, his voice carrying the weight of the challenge ahead. He noted that while the overall prevalence rate remains relatively low for now, the fight is far from over. Urban centers in the region are seeing a worrying increase in new HIV cases. The Minister cautioned against complacency, pointing to the dangers posed by misinformation spread by self-styled vigilantes and traditional healers, forces that undermine efforts to keep patients on their treatment regimens. Perhaps the most daunting challenge, however, lies in the stigma and discrimination that people living with HIV continue to face. The Minister highlighted this as an area that demands strong leadership. He called for a renewed focus on intensive behavior change communication, robust partnerships with the media, and community engagement. Only through compassion, inclusion, and accurate information, he stressed, can the region hope to close the treatment gap and make real progress in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

CHRAJ’s Steadfast Role in Ghana’s HIV/AIDS Response: Achievements, Challenges, and the Journey Ahead

At the grand inauguration of the Upper East Regional Committee of the Ghana AIDS Commission (ReCCOM), the air was filled with a sense of hope and purpose. Among the distinguished guests and partners, the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ) stood out, represented by Mr. Edmond Alagpulinsa. As he took to the podium, Mr. Alagpulinsa’s words painted a vivid story of commitment, collaboration, and resilience in the region’s ongoing battle against HIV/AIDS. Mr. Alagpulinsa began by expressing CHRAJ’s sincere gratitude to the Regional Co-ordinating Council and its partners. The recognition of CHRAJ as a strategic partner in the HIV/AIDS response, he noted, was not just an honor but a reflection of the Commission’s enduring commitment to upholding human rights in Ghana. This partnership, he explained, is deeply rooted in the CHRAJ Act, 1993 (Act 456), which mandates the Commission to investigate violations of fundamental rights and freedoms, injustice, corruption, abuse of power, and unfair treatment by public officials. This legal framework, Mr. Alagpulinsa underscored, extends protection to all citizens, including those living with HIV/AIDS. He highlighted that the Ghana AIDS Commission Act, 2016 (Act 938), spells out specific rights for persons living with HIV/AIDS, and CHRAJ is duty-bound to actively promote and protect these rights. “Our role in defending the rights of persons living with HIV/AIDS,” he said, “is not just important, it is absolutely critical.” The journey, as Mr. Alagpulinsa described, has been one of seeking out strong partnerships to fulfill CHRAJ’s mandate. Organizations such as WAPCAS, the Ghana AIDS Commission, and Hope for Future Generations have been steadfast allies. Through these collaborations, CHRAJ has empowered its staff and focal persons on HIV/AIDS with specialized training. They have been educated on the Legal Aid Commission Act, with a particular focus on the rights of persons living with HIV/AIDS, strategies to combat stigma and discrimination, and the principles of Alternative Dispute Resolution. This training, Mr. Alagpulinsa emphasized, has equipped the Commission’s team with the knowledge and skills necessary to handle the sensitive cases reported by those living with HIV/AIDS in the region. In addition to training, CHRAJ has actively engaged with individuals at risk of contracting HIV/AIDS. Periodic outreach sessions, conducted in collaboration with Hope for Future Generations, have made a tangible impact. Participants in these sessions not only learn about their fundamental rights but also find a safe space to resolve personal and domestic issues. “These engagements are more than educational, they are transformative,” Mr. Alagpulinsa remarked. CHRAJ’s approach, he explained, is both human-centered and friendly, making the Commission accessible to those who need it most. Persons living with HIV/AIDS now feel more comfortable and confident in approaching CHRAJ with their complaints, knowing they will be treated with dignity and respect. The Commission’s support goes beyond legal redress; counseling services are provided, and ongoing education about rights and freedoms is a cornerstone of their work. Yet, Mr. Alagpulinsa did not shy away from discussing the formidable challenges CHRAJ faces. Among the most pressing issues is the lack of adequate logistics. Limited resources have made it difficult for the Commission to conduct regular public education and outreach activities. The cost of securing airtime on radio stations, an essential platform for public sensitization, has become prohibitive. Similarly, organizing direct engagement sessions with the public is often hampered by financial constraints, restricting the Commission’s ability to meet the growing demand for its services. Stigma and discrimination, Mr. Alagpulinsa explained, remain persistent obstacles. He shared the story of an elderly woman in the municipality, ostracized and assaulted simply because of perceptions surrounding her HIV status. On several occasions, CHRAJ had to step in, providing protection and standing as a shield against the community’s prejudice. Such cases, he noted, illustrate the deep-seated challenges that go beyond legal mandates and require a collective effort to address. Another significant challenge lies in inter-institutional collaboration. Sometimes, cases reported to CHRAJ intersect with issues outside its jurisdiction, necessitating cooperation with other state institutions. However, this collaboration is not always as effective as it should be, leading to gaps in service and, at times, frustration for those seeking help. Mr. Alagpulinsa stressed the importance of strengthening these partnerships to ensure a seamless support system for persons living with HIV/AIDS. Despite these hurdles, CHRAJ remains undeterred. The Commission’s achievements, empowering staff, educating communities, providing counseling, and serving as a beacon of hope for vulnerable individuals, are a testament to its unwavering dedication. “All our services,” Mr. Alagpulinsa concluded, “are provided free of charge. Our doors are always open at the Regional Co-ordinating Council block.” As the event drew to a close, the story of CHRAJ’s contributions, achievements, and challenges resonated with all present. It was a call to action, a reminder that the fight for the rights and dignity of persons living with HIV/AIDS is a shared responsibility, and that with continued collaboration, compassion, and commitment, a brighter future is within reach for the Upper East Region and beyond. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

UER: ReCCOM Inaugurated to Tackle Issues Against HIV/AIDS

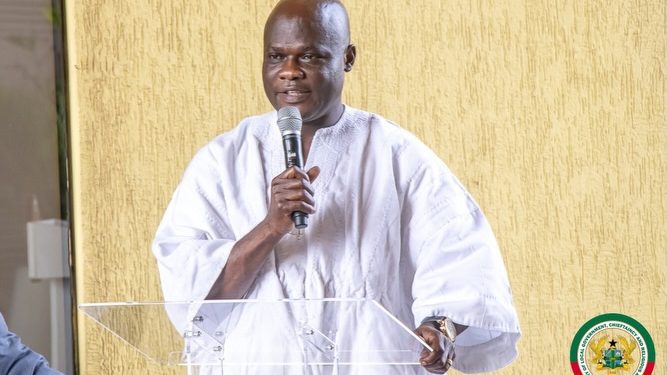

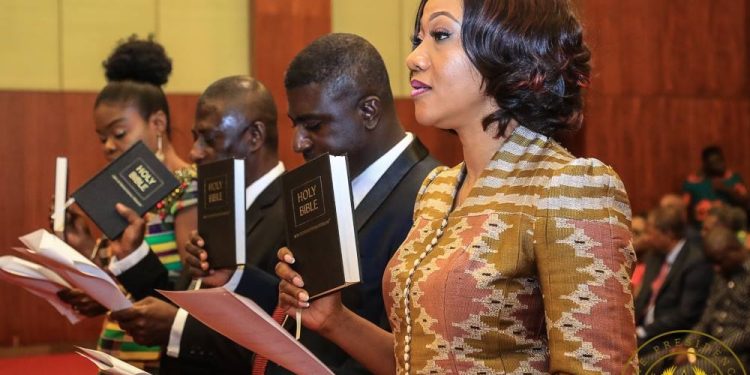

In line with section 9(1a) and 9(2) of the Ghana AIDS Commission Act, 2016 (ACT 938), the Upper East Regional Coordinating Council has inaugurated the Upper East Regional Committee of the Ghana AIDS Commission (ReCCOM). At the center of this gathering stood Donatus Akamugri Atanga, the Upper East Regional Minister, his presence radiating a blend of solemn responsibility and steadfast optimism. As the appointed Chairman of the Committee, he addresses a crowd representing every facet of the region’s social fabric. His words, as he took the podium, would chart a new course in the region’s response to HIV and AIDS, one rooted in unity, compassion, and shared resolve. “Distinguished guests, members of the committee, and esteemed colleagues,” Mr. Akamugre began, “it is with a deep sense of purpose, responsibility, and optimism that I warmly welcome you to this significant gathering.” He paused, surveying the attentive faces before him. Today’s event, he reminded them, was not merely the formation of another bureaucratic body. Rather, it was the renewal of a collective pledge, a declaration that the fight against HIV and AIDS would be met with reinvigorated energy, ideas, and collaboration. “For years, Ghana has made commendable progress in the fight against AIDS,” he continued, “yet the Upper East Region, like many others, still faces stubborn challenges.” These included not only medical and logistical hurdles but deeply entrenched social and economic issues that touched every home, every sector, and every individual in the region. The task ahead, he emphasized, required more than just government directives; it called for a harmonized effort from every corner of society. Mr. Akamugre traced the foundation of this renewed fight to the Ghana AIDS Commission Act of 2016 (Act 938), which fortified the institutional framework for the national response and provided the legal backing for a coordinated, multi-level approach. This legislative backbone, he noted, gave the region both the mandate and the tools to strengthen partnerships, harmonize interventions, and ensure that no community was left behind. He looked around the room, his gaze resting on the newly appointed committee members. “The assessment and inauguration of this committee are crucial steps in deepening decentralization and ensuring that our regional response is strategic, inclusive, and sustainable,” he asserted. The committee’s work, he underscored, was central to the broader regional development agenda. The Minister’s tone grew more urgent as he addressed the true nature of HIV: “The AIDS pandemic is not merely a health issue, but a social and economic canker. HIV has no respect for profession, tribe, religion, or status. So, our fight must have no boundaries.” He called for the dismantling of silos and the forging of new alliances, between state actors, the private sector, traditional authorities, and religious leaders. Addressing these gatekeepers of culture and conscience directly, he urged them to use their influence to dispel myths, reshape harmful narratives, and encourage testing and treatment without fear or discrimination. To civil society, he extended a special acknowledgment: “You represent the voice of the vulnerable, serving as a bridge between policy and people. You are the engine of community action in this campaign.” Turning to the committee members, Mr. Akamugre reminded them of the weighty responsibility they had accepted. “Ours is a call to service. We are expected to coordinate efforts, drive public education, protect the vulnerable, challenge stigma, and ensure accountability to the very people we serve.” He challenged each member to approach their work with professionalism, integrity, and a sense of urgency. He expressed confidence that the diversity of backgrounds and experiences within the committee would enrich its work and bring innovative solutions to the region’s most pressing HIV-related challenges. As Chairman, he pledged his unwavering support, promising that the Regional Coordinating Council would provide the leadership, institutional support, and strategic coordination necessary for success. Collaboration, he insisted, would be at the heart of their efforts. The Council would work closely with the Technical Support Unit of the AIDS Commission, civil society organizations, and all relevant stakeholders to achieve the ambitious 95-95-95 global target: 95% of people living with HIV know their status, 95% of those diagnosed are on sustained antiretroviral therapy, 95% of those on treatment achieve viral suppression. The Regional Minister shared the sobering statistics from the 2024 National and Sub-National HIV Estimates. The Upper East Region, he reported, had 7,549 people living with HIV, including 345 new infections, representing a regional prevalence of 0.85%. However, only 49.4% of those affected were receiving antiretroviral therapy. “These numbers reveal a significant gap that we must urgently address if we are to reach our targets and end AIDS as a public health concern by 2030,” he said. While the prevalence rate was relatively low, he warned against complacency. Urban centers were experiencing a rise in new cases, and misinformation from self-styled vigilantes and traditional healers continued to undermine adherence to treatment. More daunting still was the persistent stigma and discrimination faced by people living with HIV. “This is one critical area where we must show strong leadership,” the Minister emphasized. He called for intensive behavior change communication programs, robust partnerships with the media, and community-level engagement to promote compassion, inclusion, and the dissemination of accurate information. He highlighted another critical pillar of the committee’s work: resource mobilization. The effectiveness of regional and sub-national interventions, he noted, depended on securing the funding and logistical support necessary to implement evidence-based programs. As his speech drew to a close, Mr. Akamugre further congratulated the committee members on their nomination and thanked the governing board of the Ghana AIDS Commission for their trust. “We accept this responsibility with profound humility and determination, fully aware that the fight against HIV is not for one institution alone, but a shared responsibility.” He then made the official declaration: “It is my singular honor and privilege to declare the Upper East Regional Coordinating Council Committee of HIV-AIDS duly inaugurated, here on the 10th day of November 2025.” The ceremony reached its emotional pinnacle as Circuit Court Judge Sumaila M. Ahmadu, representing the High

Leprosy: Upper East Region recorded 188 official cases between 2019 to September 2025

Between January 2019 and October 2025, the Upper East Region of Ghana quietly recorded 188 cases of leprosy, a disease as old as civilization, yet as misunderstood and feared as ever. Apexnewsgh reports These numbers, dry on paper, conceal stories of courage and struggle, of families fractured and communities forever changed. At the center of this unfolding story is Eric Dakura, the Disease Control Officer at the Upper East Health Directorate, whose daily work illuminates the dark corners where leprosy still hides. Eric’s insight and passion were brought to light in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. With a clinical calm that betrays deep empathy, Eric decoded the disease for viewers: “Leprosy is a disease of the skin and the nerves. If you don’t get the treatment early, it will affect your nerves and finally lead to the wasting of your feet or your fingers, and that can lead to disability.” Unlike most diseases, leprosy’s touch is silent. Its symptoms can take years—sometimes three, five, even twenty- to appear after infection. “It’s not like any other disease that when you get infected within a week or two weeks, you get the signs and symptoms,” Eric explains. “It can be in you for over three years, up to twenty or even more years until it begins to manifest.” The first warning is often a pale, painless patch on the skin. Because these patches neither itch nor hurt, they are easily dismissed—until the disease has already begun its devastating work. “Leprosy doesn’t cause pain,” Eric says. “That is why you can see somebody with their fingers being chopped off, but there is no pain… if you even put them into fire, they will never feel anything because the nerves are all destroyed.” The destruction of nerve endings is what makes leprosy so dangerous and so easy to miss. Eric recalls a haunting case from his rounds: “A girl found a three-inch nail in her foot last year. She didn’t even know it was there because all the nerves were affected.” By the time many are diagnosed, the disease has already stolen their ability to feel, to move, or even to recognize when they are hurt. Early detection remains the greatest challenge. “We always get to know leprosy at a later stage, when the hands and the feet are gone. We don’t want to be recording cases at that stage because it means that our surveillance system is not the best.” The region now grades leprosy cases by disability: some show no deformities, some suffer numbness, while others arrive with missing fingers, feet, or affected eyes. Leprosy is endemic in all districts, but certain areas—like Bongo—have become persistent hotspots. There is progress, though: the annual number of new cases has dropped, from 32 in 2020 to just 16 currently on treatment. Yet Eric cautions that declining numbers are not always comforting. “If we record a lot of cases, it’s also good—meaning we are fishing out the hidden cases and treating them. But if we feel the numbers are declining, that could also be dangerous. We must always be on the watch.” Leprosy respects no boundaries. It is not hereditary, nor confined to the poor or the old. “Seventy percent of cases are male, but the youngest can be just two years old,” Eric shares. “There is no age that is exempted. Everybody, males, females, we are all at risk of getting it.” Yet there is hope, because leprosy is curable. “Leprosy is curable. That has always been the slogan. Just come, we’ll treat you and you’ll be fine,” Eric says, his tone unwavering. The medication, though costly for the government, is provided free of charge. “Wherever you are, the medicine can come to you, even your home.” But for all the medical progress, the greatest struggle is not clinical, but social. The shadow of stigma still looms large. “If you are affected, and unfortunately you lose your legs, there’s no way the person will be able to make life meaningful for himself. Even my own children, they dissented me. People that I used to eat with, they can’t eat with me,” Eric recounts, echoing his patients’ pain. He urges empathy and shared responsibility: “The fact that it hasn’t manifested in you doesn’t mean you don’t have it. So we just have to believe each other as people. When somebody has a problem, that is also your problem.” Often labeled a “disease of the poor,” leprosy’s grip is strengthened by poverty and neglect. “Almost all the people who are largely affected are people who come from poor living conditions. Eighty to ninety percent of the cases are in Africa. Because Africa is highly impoverished,” Eric explains. Still, hope guides his work. Through outreach, education, and persistent surveillance, the region edges closer to a day when leprosy is history. “If we get to a point where in a population of about 10,000, only one person is likely to have it, that is the aim,” Eric says. “So, in years to come, a generation will come that will not suffer from this kind of disease.” Until then, the story of leprosy in Ghana’s Upper East is one of vigilance, hope, and the unyielding human spirit, a story that, thanks to people like Eric Dakura, is no longer shrouded in shadows but moving steadily toward the light. WATCH THE VIDEO DOCUMENTARY: Source: Apexnewsgh.com/ Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

Unmasking Leprosy: The Vigil of Eric Dakura in Ghana’s Upper East

In the Upper East Region Health Directorate, Eric Dakura carries a burden few understand. As the disease control officer for leprosy and neglected tropical diseases, Eric’s days are filled with the stories and scars of those too often overlooked. His mission is clear: to confront the truth about leprosy, dispel the myths that shroud it, and rally his community to vigilance. Eric’s perspective comes not from textbooks, but from years on the ground—a reality he shared in the eye-opening documentary, “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. “Leprosy is a disease of the skin and nerves,” Eric explains to viewers. “If you don’t get treatment early, it will affect your nerves and finally lead to the wasting of your feet or fingers. That can lead to a disability.” Unlike other diseases, leprosy creeps. “It takes a longer time for someone affected with leprosy for you to see the signs and symptoms,” Eric says. “It can be in you for over three years, sometimes up to five, ten, or even twenty years before manifesting.” The stealth of the disease is part of its cruelty. By the time patches appear on the skin, often painless and easily ignored, the damage may have already begun. Eric describes the devastation with a clarity that stirs the heart. “It comes in the form of patches all over your body. The unfortunate thing is those patches don’t pain. You can see somebody with fingers being chopped off, but there’s no pain. If you even put them into fire, they will never feel anything because the nerves are all destroyed.” He recalls shocking moments discovered through his medical rounds: “Three-inch nails have penetrated people’s feet without them knowing. The nerve that is supposed to signal pain is destroyed, so we often detect leprosy at the later stage, when the hands and feet are gone. We don’t want to be recording cases at that stage because it means our surveillance system is not the best.” The tragedy, Eric insists, is that it doesn’t have to be this way. Early detection is possible, if only people know what to look for and seek help without fear. “You might see a patch on your body that doesn’t hurt, don’t ignore it. If you have a relative who has ever had leprosy, the probability of contracting it in the family is higher. It’s a slow-acting disease.” Yet, the path to diagnosis is often littered with hurdles. “Most clinicians are not able to detect leprosy early, mistaking it for other skin conditions. It’s a disease that cannot be managed by any other medicine apart from the special drugs designed to cure it,” Eric explains. The lack of awareness among both the public and some professionals allows leprosy to hide in plain sight, surfacing only when it’s too late. Perhaps the greatest enemy, Eric says, is not the bacteria, but stigma. “One of the biggest challenges with leprosy is stigma. If you have it, people around you may not want to come close because they feel they could also be infected. But leprosy is curable. Just come, we’ll treat you and you’ll be fine.” Eric works hard to spread this message of hope. He reminds everyone that leprosy treatment is free and accessible to all, with no hidden costs. “There is no cost component attached to leprosy treatment. It has always been free, irrespective of how long you take it. If you have skin conditions that are not responding to treatment, consult your health facility.” The Upper East Region, Eric reports, has seen progress. “We currently have ten cases under treatment, a significant improvement from previous years. If we record a lot of cases, it means we are fishing out the hidden cases and treating them. But we must never let our guard down.” Eric is quick to confront the misconceptions that have allowed leprosy to fester in secrecy. “Leprosy is not hereditary, nor is it a ‘poor man’s disease’ alone. It can affect anyone, at any age. But poverty increases vulnerability because of poor living conditions.” Eric’s determination remains undimmed. He ends with a call to action, one he repeats to every community he visits: “Stigma and late detection are our biggest enemies. ‘Leprosy is curable’ is our slogan. Let’s all do our part to detect, treat, and eliminate this disease from our communities.” In the story of leprosy in Ghana’s Upper East, Eric Dakura is more than a health officer, he is a sentinel. His vigilance, empathy, and unflagging hope offer a path forward, one where the pain of the forgotten gives way at last to healing and acceptance. WATCH THE VIDEO DOCUMENTARY BELOW: Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

Breaking the Chains of Stigma: Tahiru Suleman’s Fight for Inclusion in Bongo

Where the red earth stretches beneath acacia trees and the air hums with the rhythm of rural life, one man’s voice rises above the silence that too often surrounds the lives of leprosy survivors. Apexnewsgh reports Tahiru Suleman, the Assistant Assembly Member for the Awukabisi Electoral Area, is on a mission to transform not just policies, but hearts and minds. Tahiru’s journey began with a simple but painful observation: “In our community and electoral area, we have a lot of people suffering from leprosy. Just within my electoral area, I can pinpoint about four or five people who are infected.” Yet the challenges facing these individuals go far beyond their diagnosis. Their true struggle is against an invisible enemy: stigma. This hard reality was laid bare in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. Tahiru, speaking with a blend of compassion and urgency, described what he saw: “These people go through a lot. When they are seen in public, people run away from them. Some even think that if the saliva of someone with leprosy touches them, they will be infected.” For those living with leprosy, every day is a test of endurance. Beyond the pain of their disease is the pain of rejection. Tahiru detailed the myths that persist, deeply rooted in local lore: “Some people think leprosy is a curse from certain families, but that is not true. Leprosy can attack anybody.” To make his point, he shared the story of a close colleague who, despite years of good health, unexpectedly contracted leprosy. “If someone had told him in the past that he would have this disease, he wouldn’t have believed it.” The stigma is isolating. Many affected individuals lose their livelihoods, shunned not just by neighbors but sometimes even by their own families. “Because of the disease, some of them cannot do any active work. Even within their families, people don’t want to associate with them. For some, even getting food to eat is a big problem,” Tahiru explained, his voice heavy with empathy. Moved by these injustices, Tahiru has become an outspoken advocate for change. He passionately calls upon health authorities, NGOs, and the general public to intensify education about leprosy. “What they need is love, not rejection. We must all help fight the stigma.” But Tahiru’s campaign does not end with leprosy. He recognizes that those living with Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) across Bongo face similar challenges. “I think it is our responsibility as Assembly Members to educate the community members about the ongoing stigmatization and discrimination against people living with NTDs in our communities,” he said. Public education, he believes, is the most effective antidote to fear and ignorance. “There is a need for people to know the dangers of discriminating against these people.” Yet, progress is not easy. Tahiru describes the frustration of working alone: “Our challenge has to do with community members not listening to us individually in this direction.” His answer is to build partnerships with health workers, who bring not only expertise but also credibility to community education efforts. “There is a need for health workers to make themselves available for such exercises in the community.” For Tahiru, real change will come only when local leaders, health professionals, and ordinary citizens unite in purpose and compassion. He envisions a future where those affected by NTDs can walk freely, participate fully, and live with dignity. “Ending stigma requires a united front,” he insists. “Only then can we create an environment where those affected can live with dignity and hope.” The seeds of change are already being planted, thanks to organizations like the Development Research and Advocacy Centre (DRAC). With support from Anesved Fundación, DRAC has drilled ten boreholes in Bongo and nearby communities, bringing clean and safe water to thousands. Water health committees now teach hygiene practices that are essential to fighting NTDs and breaking cycles of disease. But perhaps DRAC’s most transformative work lies in economic empowerment. Basket weaving and soap-making are not merely trades; they are lifelines. DRAC supplies materials, offers training, and connects artisans directly to buyers. “Buyers come to the community to purchase baskets, and we provide materials and training,” explains Executive Director Jonathan Adabre. For many, these initiatives restore not just income, but pride, purpose, and belonging. The story of Bongo’s leprosy patients and NTD survivors is, at its heart, a story of resilience. It is written in the determined footsteps of nurses on their rounds, the laughter of women weaving baskets, and the hope that flows with every borehole drilled. It is a story that calls for more than sympathy—it demands action, understanding, and a commitment to never again let these lives be forgotten. As the sun sets over Bongo, Tahiru Suleman’s voice continues to echo, a reminder that the true measure of a community is found in how it treats its most vulnerable. His fight is not just for awareness, but for acceptance; not just for support, but for solidarity. In breaking the chains of stigma, Bongo can become a place where everyone belongs, and where dignity is a right, not a reward. WATCH THE VIDEO DOCUMENTARY BELOW: Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

DRAC’s Mission to Eradicate Neglected Tropical Diseases in Ghana’s Upper East

The quiet battle against Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) is gathering new momentum. At the forefront of this fight is the Executive Development Research and Advocacy Centre (DRAC), an organization determined to bring health, hope, and dignity to some of the country’s most marginalized people. Apexnewsgh reports The story of DRAC’s mission unfolds in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” where Executive Director Jonathan Adabre shares his vision for a future free of the pain and stigma that have haunted families for generations. “We want to talk about the early manifestations of diseases like leprosy, meningitis, and yaws,” he explains. “If community members can recognize the signs, understand transmission, and know what treatment looks like, we can stop these illnesses before they destroy lives.” For decades, myths and misinformation have allowed diseases like leprosy to spread in silence. Many in the region still believe leprosy is hereditary, passed from mother to child—a belief that Adabre is determined to dispel. “Leprosy can take up to 20 years to show symptoms,” he clarifies. “A mother may unknowingly transmit it, and when her child develops symptoms much later, people assume it’s genetic. That’s the misconception we want to kill.” But the battle is not fought with education alone. DRAC’s strategy is deeply rooted in community collaboration. Chiefs, queen mothers, and local opinion leaders are enlisted as partners in the fight against stigma and discrimination. “We want affected persons to live dignified lives,” Adabre insists. “They should participate in community activities, share their views, and not be sidelined by fear.” Yet, changing minds is only part of the challenge. Inadequate sanitation and water access fuel the spread of NTDs. “Without water, people can’t wash, bathe, or keep their clothes clean. Transmission happens quietly,” Adabre notes. With support from the Anesvad Foundation, DRAC has drilled boreholes in several communities and established wetlands committees to manage these vital resources. The ripple effects are already being felt. A recent baseline survey conducted by DRAC revealed a sobering fact: 97% of respondents still practice open defecation, perpetuating health risks and undermining efforts to contain disease. To address this, DRAC is working closely with community health management committees and local leaders, pushing for behavioral change and better sanitation practices at every level. But health is only the foundation, DRAC recognizes that a future free of NTDs depends on economic empowerment as well. In many villages, basket weaving is part of the cultural heritage, but a lack of capital and market access keeps families in poverty. DRAC’s solution is to provide not just materials but direct connections to buyers, ensuring that the fruits of local labor reach wider markets. Training in soap and detergent making complements this initiative, promoting hygiene and providing an extra source of income. Crucially, DRAC’s work is shaped by the voices of those directly affected. “In this country, we have the habit of not listening to people before providing support,” Adabre observes. To change this, DRAC is helping form associations so that those living with NTDs, and their caregivers, can advocate for themselves. They share stories of stigma and exclusion, and highlight missed opportunities, such as the government’s LEAP program, which too often passes them by. Access to health care is another barrier DRAC is determined to break down. By partnering with the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), the organization is bringing registration and renewal services directly to vulnerable populations, ensuring no one is left behind for lack of paperwork or travel money. The impact of DRAC’s approach is already apparent. Adabre recalls a striking moment from an awareness session: “An assembly member told us, ‘Are these signs really leprosy? I see them on my wife.’ When she was tested, it came back positive. That shows why early detection is critical.” For Mr. Adabre, the national goal is clear: “We want to eradicate skin NTDs in Ghana. It doesn’t take much, just consistent commitment and attention to the most vulnerable.” Through a blend of awareness-raising, improved water and sanitation, economic opportunity, and access to healthcare, DRAC is not just fighting disease; they are building resilience, breaking the cycle of stigma, and restoring hope to communities long forgotten. Their story is a call to action: that with compassion, partnership, and persistence, even the most neglected battles can be won. Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

I don’t know why God gave me a disease that people don’t respect—Mr. Ayuumbeo leprosy patient, cries

Once upon a time, in the lively community of Bongo Soe, Mr. Adombire Ayuumbeo was the embodiment of diligence and pride. The sun’s first rays often found him by the dam near his house, tending to rows of tomatoes and vegetables. His farm was a patchwork of green, a source of sustenance for his family and a modest income from the surplus sold in the market. But farming was only a part of his industrious life; Mr. Ayuumbeo also spent hours cutting firewood and harvesting roofing grass, always ensuring his household’s needs were met. His hands, once strong and skilled, provided security, comfort, and hope to those who depended on him. This story, however, took a drastic turn. Leprosy crept silently into Mr. Ayuumbeo’s life, robbing him of the very tools of his trade, his fingers. The disease did not merely bring pain and disfigurement; it stripped him of his ability to work, leaving him “idle and helpless.” Once a man who never sat still, he now found himself confined to his home, watching the world move on without him. “When I remember the way I used to work and support my family, tears start pouring from my eyes,” Mr. Ayuumbeo confided in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. “Now I can’t farm, I can’t cut firewood, I can’t do anything. Sometimes I think I should die than to live.” For Mr. Ayuumbeo, the greatest agony is not only physical, but also the heavy shroud of stigma that leprosy brings. Once greeted with respect, he now feels abandoned and judged by the very people he once called neighbors and friends. “You don’t have anything, and your body too makes it hard to mingle with people. People stigmatize you. I don’t know why God gave me a disease that people don’t respect.” The sense of isolation is profound. The silence from others echoes louder than his disability, and the weight of judgment is heavier than any load he once carried from the fields. Despite these trials, Mr. Ayuumbeo tries to hold onto gratitude. “I thank God that the sores have healed and I can walk without difficulty. But I cannot do what I used to do.” His gratitude is laced with sorrow—a longing for lost strength, lost routine, and lost purpose. Each day, he wakes to face both the physical limitations of his body and the invisible barriers erected by society’s misunderstanding. His thoughts often return to his family. With a wife and children looking to him for support, the burden of helplessness is magnified. He worries about their future, how to keep them fed, clothed, and safe. “When I was active, I used to pay taxes. Now I cannot work, but I still belong to the government. I vote. I have my voter ID. The government of Ghana owes me and my family. If there’s any way they can help us sustain our lives, they should do it.” His appeal is not just for himself, but for every leprosy survivor who has been left behind, still a citizen, still deserving of dignity and support. Mr. Adombire’s story is woven into the larger tapestry of Bongo’s leprosy survivors—a tapestry colored by pain, but also by resilience and hope. Organizations like the Development Research and Advocacy Center (DRAC) are working to ensure that people like Mr. Ayuumbeo are not forgotten. DRAC’s efforts go beyond charity; they are about rebuilding lives. With the drilling of ten boreholes, clean water is now within reach for many who once struggled. Water health committees educate communities about hygiene, crucial in the fight against neglected tropical diseases. But perhaps most remarkable is DRAC’s commitment to economic empowerment. Training sessions in basket weaving and soap-making provide patients and caregivers with skills, materials, and, most importantly, a renewed sense of purpose. “Buyers come to the community to purchase baskets, and we provide materials and training,” says Jonathan Adabre, DRAC’s Executive Director. These initiatives are more than income; they are threads of dignity, restoring connections to the community and to self-worth. Across Bongo, the story of leprosy is changing. It is no longer solely a tale of suffering, but one of resilience written in the determined footsteps of a nurse on his rounds, in the laughter of women weaving baskets, and in the hope that arrives with every borehole drilled. Yet, Mr. Ayuumbeo’s plea still rings out, a call for compassion, inclusion, and meaningful action. His journey, and that of so many others, is a reminder that the scars of leprosy go beyond the physical. It is up to all, the community, government, and organizations, to ensure these lives are lifted from the silence of stigma into the light of dignity and support. Only then will the story of Bongo’s leprosy survivors be one not just of what was lost, but of what can still be regained. WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY VIDEO Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

The Unseen Battles of Leprosy Survivors in Bongo

For ten long years, Matilda Nyaaba endured a mysterious torment. In her quiet village of Bongo Balungu, life was punctuated by fainting spells, nosebleeds, and unexplainable pain. Apexnewsgh reports Each episode left her weaker, and each visit to yet another health facility only compounded her confusion. What was this invisible enemy that drained her strength and hope, year after year? No one seemed to have an answer. Matilda’s ordeal was brought to light in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. Her story, like those of many leprosy sufferers, was one of searching in the dark. Even as her family stood by her, her neighbors whispered, eyed her with suspicion, and kept their distance. Some said she was cursed; others assumed she had HIV. To protect herself from the sting of their words, Matilda began to retreat indoors, leaving her home only for the most essential of chores. The isolation bit deeper than the disease itself, eroding her spirit and sense of belonging. It was only after a particularly harrowing episode, a collapse so severe she was rushed to the hospital, that a turning point arrived. There, a disease control officer finally recognized the signs of leprosy and placed Matilda on a monthly treatment regimen. For the first time, hope flickered in her life. The medicine brought relief, but not certainty. Supplies at the hospital ran out from time to time, and Matilda would wait anxiously for a call or a visit, never knowing when the next dose would arrive. Still, she persevered. Her wish was simple: that no one else should have to wander in confusion or suffer in silence as she had. Matilda’s journey reveals a truth often overlooked: the wounds of leprosy are as much emotional and social as they are physical. The pain of exclusion, the silence of misunderstood suffering, and the longing for dignity weigh heavily on those afflicted. Her resilience is a quiet call for compassion, understanding, and real action, so that no one else in her community will have to endure the same lonely road. Aniah’s Journey Through Leprosy’s Trials In the village of Bongo Soe, another story of quiet resilience unfolds. Aniah Lamisi was once a farmer whose days were filled with the rhythm of the land. She took pride in the sweep of her hoe, the bounty of her harvest, and the strength of her hands. Farming gave her purpose, connection, and identity. But leprosy crept into her life without warning, first as a tingling in her fingers, then as a relentless force that twisted and weakened her hands. Tasks that once came easily, cooking, fetching water, and gathering firewood, became daily struggles. The simple act of lifting a water container to her head was now a painful ordeal. Cooking over a fire brought blisters instead of warmth. With her hands disfigured, her independence slipped away, and Aniah found herself an observer in her own life, unable to work or contribute as she once did. The loss went deeper than the physical. Though her neighbors did not reject her outright, the shame of asking for help, of reaching out with altered hands for food, wounded her pride. She withdrew from communal life, carrying her pain in silence. Like Matilda, Aniah’s only hope was regular medication—but the health center’s supplies were unreliable. Some months, she received her treatment; other times, she waited in vain, watching her health and hope falter. Each missed dose was a reminder of how fragile her world had become. Yet Aniah’s spirit refused to break. In rare quiet moments, she counted her blessings: a body that still allowed her to dress herself, fleeting moments of calm, and the knowledge that others faced even greater struggles. She dreamed of something more, a chance to learn a trade, to regain purpose, to earn her own living. Vocational training, she thought, could be a bridge back to dignity and self-respect. While Matilda and Aniah’s stories are deeply personal, they are not unique. Across Bongo and its surrounding communities, many battle the same invisible foe, facing not just disease but the crushing weight of stigma, poverty, and uncertainty. But hope comes not only from within. Organizations like the Development Research and Advocacy Center (DRAC) are changing the landscape for leprosy patients. With ten boreholes drilled in affected areas, access to clean water is no longer a dream. Water health committees teach hygiene, helping prevent further spread of neglected tropical diseases. Most transformative are DRAC’s economic empowerment programs, training in basket weaving and soap-making, providing materials, and connecting patients with buyers. For women like Aniah and Matilda, these opportunities are more than a source of income; they are a path back to belonging and pride. The story of Bongo’s leprosy survivors is one of resilience, not just suffering. It is written in Matilda’s quiet hope, in Aniah’s determination, in every basket woven and every borehole drilled. It is a story that demands not pity, but recognition and commitment. For these women and countless others, the journey continues toward healing, dignity, and a future where no one must walk alone in the shadows. WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY VIDEO; Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen