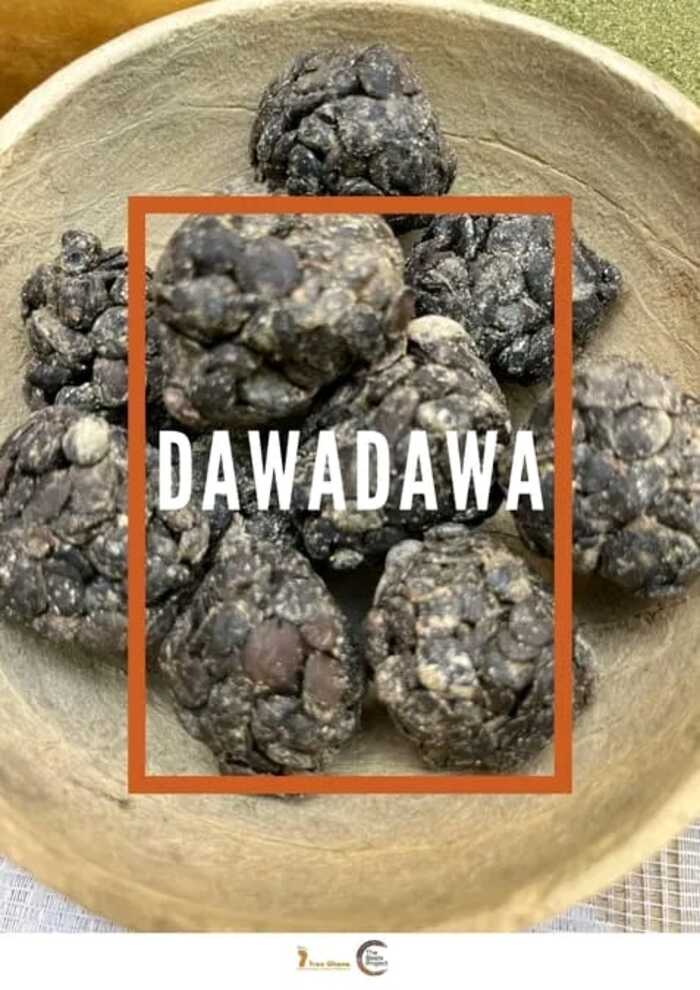

Dawadawa is more than a seasoning. It is memory, nutrition, economy, and sustainability woven together in flavor. In many West African kitchens, there is a defining moment when a pot of soup begins to deepen in character. Onions have softened, peppers have blended into the base, and palm oil or shea butter shimmers with heat. Then comes the quiet but transformative addition — a small ball or paste of fermented locust beans. The aroma shifts instantly, earthy and complex. That unmistakable scent signals something profound: dawadawa has entered the dish.

Made from the fermented seeds of the African locust bean tree, scientifically known as Parkia biglobosa, dawadawa has nourished communities across West Africa for generations. Known by different names — iru among the Yoruba, soumbala in parts of the Sahel — it remains one of the region’s most treasured indigenous condiments. Its essence is simple yet powerful: carefully fermented seeds shaped by knowledge passed down through time.

The African locust bean tree stands resilient across the savannah landscapes of Ghana, Burkina Faso, Mali, and northern Nigeria. It thrives in dry climates where other crops struggle, offering shade, soil enrichment, and food security. The tree’s long pods contain sweet yellow pulp enjoyed as a snack, but it is the hard brown seeds that become dawadawa. For many rural communities, this tree is not just vegetation; it is livelihood, nourishment, and ecological stability.

The tree contributes quietly to sustainable agriculture. It enriches soils through nitrogen fixation, reduces erosion, and integrates naturally into traditional parkland farming systems. Farmers often preserve it within their fields rather than cutting it down, recognizing its value. Long before climate resilience and regenerative agriculture became global buzzwords, West African communities were practicing them through their relationship with this tree.

Dawadawa is not simply harvested; it is crafted through labor and patience. The process begins during harvest season when ripe pods are collected. The pods are boiled to soften the pulp and release the seeds. After washing, the seeds undergo hours of cooking to soften their tough coats. Women — often working collectively — remove the seed coats by pounding and washing, a physically demanding task that requires strength and skill.

Once cleaned, the seeds are boiled again and then wrapped in leaves or placed in covered containers to ferment naturally over several days. It is during fermentation that transformation occurs. Microorganisms break down complex compounds, producing the deep umami flavor that defines dawadawa. The seeds darken, soften, and develop their characteristic pungent aroma. No artificial additives are required. Time, heat, and microbial life do the work.

This fermentation knowledge is rarely written down. It is carried in memory and practice, passed from mothers to daughters and elders to apprentices. Women know by touch, scent, and experience when fermentation is complete. The craft reflects an intimate understanding of natural processes, developed long before modern food science offered explanations.

Beyond its distinctive flavor, dawadawa is nutritionally significant. It is rich in protein, making it an essential supplement in communities where access to animal protein may be limited. It contains beneficial fats, calcium, iron, and B vitamins.

Fermentation enhances digestibility and increases the availability of nutrients. In households with constrained incomes, a small portion can transform a simple pot of soup into a nutrient-dense meal.

In northern Ghana, dawadawa defines beloved soups such as ayoyo and groundnut soup. In Nigeria, iru enriches egusi and ogbono soups. Across the Sahel, soumbala flavors stews served with millet or couscous. Each region shapes and prepares it slightly differently, yet the shared cultural thread remains strong. For many in the diaspora, its aroma evokes childhood kitchens, communal meals, and the steady rhythm of family life.

Unlike imported bouillon cubes that increasingly fill market shelves, dawadawa carries no anonymous industrial origin. It carries the story of harvest seasons, of women gathered under shade trees pounding seeds, of conversation and laughter during fermentation days. In this way, it anchors communities to ancestral foodways even as globalization reshapes consumption patterns.

Women stand at the center of dawadawa production and trade. Across Ghana’s Upper East, Northern, and Upper West regions, they harvest, process, and sell the condiment in local markets. Income from sales supports households, pays school fees, and strengthens women’s financial independence. The work is demanding, but it is also empowering.

On market days, woven baskets lined with leaves display carefully shaped balls of fermented seeds. Buyers inspect texture, inhale aroma, and negotiate prices.

Knowledge of quality is shared openly — whether fermentation is adequate, whether moisture levels are right, whether the product will store well. Markets become spaces of both commerce and cultural exchange.

Modern discussions about sustainable food systems often emphasize reducing carbon footprints, promoting biodiversity, and strengthening local supply chains.

Dawadawa embodies these principles naturally. Its primary ingredient grows locally with minimal external inputs. Production requires no imported chemicals. Distribution typically happens within short distances between producers and consumers.

The African locust bean tree supports biodiversity and integrates into agroforestry systems. By preserving the tree, farmers maintain ecological balance. In a world increasingly reliant on long and fragile global supply chains, dawadawa demonstrates the resilience of localized food systems grounded in community knowledge.

Yet challenges persist. Urbanization and shifting dietary preferences have led some consumers to favor imported seasonings perceived as more convenient. Younger generations may see traditional processing methods as labor-intensive. Climate change threatens tree populations through prolonged droughts and land degradation. Limited access to improved equipment can also constrain production quality and scalability.

Within these challenges lie opportunities. Cooperatives can strengthen bargaining power. Improved packaging and hygiene standards can expand markets while preserving authenticity. Agroforestry initiatives can promote tree conservation and planting. Culinary education can reintroduce youth to the value of indigenous foods. When tradition meets innovation respectfully, resilience grows.

Dawadawa’s importance extends beyond nutrition and economics. Food is one of the most enduring carriers of culture. Even as languages evolve and clothing styles change, taste memories remain. Preparing dawadawa teaches patience and cooperation. It honors processes that cannot be rushed without losing their essence.

At weddings, festivals, naming ceremonies, and communal gatherings, dishes enriched with dawadawa affirm belonging. In rural compounds, children learn by observing elders ferment seeds, absorbing not only technique but values of diligence and stewardship. Such transmission is intangible heritage — as vital as monuments or artifacts.

The science behind dawadawa’s aroma lies in fermentation.

Proteins break down into amino acids, producing glutamates that create savory depth. Beneficial bacteria drive this process, naturally preserving the product. Researchers increasingly recognize what communities have long known: controlled fermentation enhances flavor, nutrition, and shelf life without synthetic additives. Dawadawa bridges indigenous knowledge and modern science.

In diaspora communities across Europe and North America, African grocery stores stock dawadawa for those seeking familiar tastes. Chefs experimenting with global cuisine appreciate its umami richness, comparable to other fermented condiments worldwide.

As global interest grows, ensuring that primary producers benefit from expanded markets becomes essential. Recognition must uplift origin communities rather than detach the product from its roots.

Dawadawa endures because it adapts.

Some producers adopt solar drying techniques to improve hygiene and extend shelf life. Others form cooperatives to strengthen income stability. Agricultural initiatives promote tree preservation to secure future harvests. Yet at its core, the process remains intimate: seeds, water, fire, time, and care.

To call dawadawa merely a seasoning is to overlook its depth. It is the resilience of a tree rooted in dry savannah soils. It is the labor and leadership of women transforming seeds into sustenance. It is an affordable protein for strengthening families. It is the scent that calls children home at dusk.

It is market trade sustaining local economies. It is sustainable agriculture practiced long before it was formally named. It is a culture carried on the tongue.

In every spoonful stirred into soup lies a quiet declaration that local knowledge matters and indigenous food systems endure.

Dawadawa is heritage in flavor — fermented not only by microbes, but by memory, meaning, and community. As long as pots continue to simmer across West Africa, its story will continue to unfold, one fragrant meal at a time.

Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Prosper Adankai