Introduction

A well-established national identification (ID) system would help distinguish law-abiding citizens and non-citizens from terrorists and other criminals. It would help combat terrorism and related crimes; tackle the issue of immigration and work permits for immigrants; strategically combat identity theft; minimise tax evasion and number of welfare beneficiaries; provide proof of age; and provide relevant information in times of medical emergency, among others.

Khan (2018) examined the opportunities and threats associated with issuance of national identity cards. He found that though there are varied reasons for various governments’ resolve to adapt and implement one national identity system or the other, there is a common factor that permeates all governments’ objectives. That is, the need to create an identification system that is perfect to integrate the biometric details of each individual with a broad central database which houses or stores vast personal information. This is an ample indication of continuity in the national identification process commenced in Europe several centuries ago with improved technological features in contemporary times.

Mordini and Petrini (as cited in Khan, 2018) describe the term biometrics literally as an instrument for measuring life. Specifically, biometrics refer to the technology that is used to measure, analyse, and process digital representations of unique biological data and behavioral traits of persons, including facial patterns, finger prints, eye retinas, body odours, and hand geometry. This implies a national identification system captures vital information of a person that invariably makes him or her unique from the other. This information is accessed by governments to influence their socio-development drives for various parts of their respective economies. The foregoing affirms Khan’s (2018) study which revealed the issuance of identity cards helps issuing governments to combat fraudulent acts, illegal immigration, terrorism, and to accelerate social service delivery to targeted citizens or beneficiaries.

Krupp, Rathgeb and Busch (2013) found increasing demand for biometric technologies, and constant infusion of biometrics into the lives of individuals across the globe. Further, their study revealed nations’ resolve to make use of national identity cards mandatory leaves their citizens with only a choice. That is, come to terms with and holistically accept biometrics as part of their everyday lives. Krupp et al. (2013) affirm the inevitability of national identification systems in the socio-economic advancement of modern societies.

Combet (2004) advances three major arguments to buttress the socio-economic usefulness of discussions related to national identification systems in our current dispensation. These include increasing use of technology related to national identification systems among economies across the globe; growing need for biometric data to help the police improve on crime prevention and security, and to effectively counter acts of terrorism; and the introduction of electronic chips such as electronic authentication and signature by some countries around the world. Kitiyadisai (2004) revealed following the terrorists’ attack on the United States of America (USA) on 11th September, 2001, the need for issuance of national identity cards has been unanimous among most developed, emerging, and developing economies across the globe. Thus, national identification systems have become necessary to help governments enhance internal and external security of their citizens; and to ensure intervention programmes are effectively tailored to meet the needs of targeted beneficiaries. Rule (2005) believes the foregoing underscore various governments’ decision to make the issuance of national identity cards compulsory for all citizens.

Gemalto (as cited in Khan, 2018) examined the usefulness of national identification systems in the development of the Belgian economy. The study showed Belgium is one of the first countries in the world to embark on issuance of electronic identity cards on a national scale. The aim is to ensure citizens are provided with safe and secure electronic identity card; and to have unfettered access to public and private services in the country and online. However, the House of Commons (2005) noted the fundamental objective of enacting the Identity Cards Bill in the United Kingdom (UK); and subsequent issuance of electronic identity cards was inter alia, to promote national security interest, enforce work permit laws, detect and prevent crimes, enforce immigration controls, and to improve on the efficiency and effectiveness of public services delivery.

One observes while security concerns remain a dominant factor for the adaption and implementation of national identification system in the United Kingdom, improved service delivery remains the paramount objective for the issuance of same in Belgium. The variation in fundamental objectives could be attributed to the differences in the two countries’ exposure to internal and external security threats. Lyon (2009) notes in Hong Kong, the need to enhance and tighten border controls informed the government’s decision to introduce a sophisticated national identification system in 2003. Hong Kong’s national identification system was intended to check migrants from mainland China. In Japan, the purpose of implementing the national identification system was to gather personal information of individuals such as name, date of birth, and address; and return this information to them on a card.

The European Commission (2006) named the national identification exercise in Estonia as the most successful in Europe. The national identity card issued to Estonians has many electronic applications, including verification of bills, drivers’ licence, digital signature, health insurance, banking details, and e-ticketing. The national identification scheme in Estonia was centered on a public-private partnership.

Islam, Baniamin and Rajib (2012) found a widespread national identification scheme in Bangladesh following its gradual inception in the 1990s. The Bangladeshi government has tied the provision of twenty-two public and private services with the ownership of national identity cards; citizens who are above 18 years must acquire a national identity card to access the foregoing services. ITU (2016) indicates the national identity card doubles as a voter identity card in Bangladesh; no eligible voter is allowed to cast his or her ballot without it. The introduction of national identification system in Bangladesh is intended, fundamentally, to ease the identification of service recipients by service providers in both private and public sectors of the economy (Election Commission as cited in Khan, 2018).

Zoleta (2018) assessed the merits and demerits associated with the implementation of national identification system in the Philippines. The study revealed until the approval of the Philippine Identification System Act (Republic Act 11055) on 6th August, 2018 by President Rodrigo Duterte, the Philippines remained one of nine countries across the globe without a national identification system. Zoleta (2018) revealed national identity card in the Philippines can be used for all transactions, including acquisition of driver’s licence and passport, assess to general government services including health, job applications, tax related transactions, voter’s registration and identification, bank account openings and other financial transactions, social welfare and benefits applications, application for schools, colleges, universities, and verification and clearance on criminal records, among other essential services. The author noted some similarities in the primary functions of the national identification card in the Philippines and Belgium as found by Gemalto (as cited in Khan, 2018).

A financial inclusion survey conducted by the Bangko Sentral in the Philippines in 2017 revealed about 34% of the adult sampled population attributed their inability to apply for a bank loan to lack of identity cards. It is believed the simple process of acquiring a national identity card in the Philippines presently would allow millions of unbanked Filipinos to open bank accounts; and to access other essential banking services such as loans, investments, credit cards, and others. Implementation of national identification system in the Philippines is expected to enhance efficiency in government related transactions; queues and transaction times are expected to be shorter than before. A recent survey conducted by SWS (as cited in Zoleta, 2018) revealed about 73% of the sampled respondents supported implementation of the national identification system in the Philippines. The foregoing implies the level of acceptance of the national identification system among Filipinos is very high.

National Identification Systems in Model Economies

Recent studies revealed adaption and implementation of national identification systems have yielded varied socio-economic results in some emerging and developing economies such as India, Peru, Thailand and Pakistan. For instance, in India, implementation of the Aadhaar system helps in the generation of unique identification numbers for citizens (about 1.36 billion population); and ensures benefits and subsidies reach the targeted population. Efficiency of the Aadhaar system helped the Indian government to reduce financial waste at the early stages of its implementation. Further, it helped the Indian government to increase returns on social investments; and save to pay for the cost of the system within a short period of time. India remains the economy with the largest biometric-based identity scheme in the world (Jacobsen, 2012).

An effective national identification system continually helps the Peruvian government to send relief items, with relative ease, to affected victims in times of natural disasters. Similarly, the Thai government, through its strong national identification system, has succeeded in providing universal health coverage for the population. The identification system has helped to improve on the level of health service delivery in Peru.

Effective use of biometric technology in Pakistan helps the government to transfer financial assistance to targeted beneficiaries such as women. Beneficiaries are able to make informed and independent decisions on mode of expenditure on funds received from the government. Prior to the issuance of the national identity card, some businesses in the Philippines only accepted and honoured senior citizen identity cards. That is, cards issued to individuals who are sixty years and above. However, the Senior Citizens Law in the Philippines is clear on the presentation of any government-issued identity card by seniors to receive discounts. This prevented seniors without the senior citizen identity cards from enjoying discounts on goods and services in the country. The national identity card is expected to ease the challenges on discounts received by senior citizens when they patronise goods and services in various parts of the country. The Philippines identity card (PhilID) was expected to have enhanced security features as in banknotes, passports, and other governments’ identity cards across the globe.

Countries such as South Korea, China, Singapore, Spain, Italy, and France have taken steps to issue national identity cards to their citizens (Zoleta, 2018). Some advanced countries considering use of national identification systems include the United States of America (USA), Australia and Canada. Here, the consideration is remote; and this may be attributed to the de facto national identification in the issuance of a social security card in some of these countries; and control and privacy issues raised by anti-identity card groups in these countries. Another advanced economy which considered use of a national identification system is the United Kingdom. Consideration in the United Kingdom was immediate in spite of concerns raised by anti-identity card groups (Fussell, 2004; Neyland, 2009).

Resistance to National Identification Systems

In spite of its enormous contribution to socio-economic advancement of nations around the world, national identification systems are crept with inherent challenges that affect their outright acceptance in some jurisdictions. Zoleta (2018) revealed in recent years, websites owned by the government of the Philippines were prone to hacking. The infamous data breach in the annals of the Philippines’ history known as the Comeleak was recorded in 2016 when the personal data of about fifty-five million (55,000,000) voters were compromised. The recency of the security breach raised doubts in the minds of some Filipinos on the government’s ability to protect personal and confidential information on millions of individuals that were collected and stored in the national identification system. However, the government has affirmed her commitment to strict implementation of the Data Privacy Act (RA10173) in the country.

Zoleta (2018) found the implementation of national identification systems could lead to violation of individuals’ right to privacy. For instance, the national identification system would allow various governments an access to massive personal data of citizens and other nationals resident in their respective countries. Access to personal data could lead to government’s tracking of individual and group’s transactions. However, this tracking becomes problematic when it is blatantly abused or misused by custodians of millions of personal and confidential data.

National identity card can be used for multiple functions including financial transactions. As a result, Smith (2008) and Khan (2018) believe a card lost could have dire social and financial consequences on the original bearer, that is, the individual to whom the identity card was originally issued. This presupposes the identity card holder must ensure due diligence and adequate protection for his or her card at all times to avert any financial setbacks in the near and distant future.

Khan (2018) noted in spite of the fringe benefits associated with the implementation of the national identification system, the unanticipated, unintended, and unwelcome consequences attached to its implementation require critical assessment by key stakeholders such as governments of various geographical jurisdictions. The author believes all forms of national identity cards come with their attendant controversies. Kitiyadisai (2004) stated citizens of several countries around the world have raised objections to the implementation of national identification systems and eventual issuance of national identity cards. Neyland (2009) believes the citizens’ objections can be attributed to factors such as skeptism in governments’ ability to effectively protect and manage the multiple data of millions of citizens without security breaches.

Davies (n.d.) notes the growing voices of privacy and civil liberty campaigners are negatively affecting governments’ ability to adapt and implement technologies that identify and track transactions of individuals. Some anti-identity card groups believe the stated merits associated with the implementation of national identification systems are exaggerated and misleading; implementation of these systems could lead to serious ethical and constitutional breaches by government officials (Milberry & Parsons, 2013). To affirm the authenticity and validity of data stored in national identification systems, the London School of Economics (as cited in Davies, Hosein & Whitley, 2005; Khan, 2018) believes countries may have to repeat their biometric registration exercises once every five years.

Human fingers remain a major component of gathering reliable biometric data. As a result, injuries to or dirt on finger tips can affect recordability of finger prints. Scars or burns on fingers could lead to permanent loss of a fingerprint template. Petermann, Sauter and Scherz (2007) found eye diseases such as glaucoma, blindness and cataracts may lead to permanent loss of biometric data readability. The foregoing deficiencies may affect a victim’s (citizen’s) ability to access certain public and private services; this may have severe consequences and may limit the victim’s chances of prolonged life.

ITU (2016) notes religious considerations could negatively impact on the successful implementation of national identification systems in some jurisdictions. For instance, in Bangladesh, national identification officers have challenges carrying out their functions among conservative Muslim populations. National identification officials have arduous tasks taking the biometrics of women, including iris scans and photographs in Muslim dominant areas. Kitiyadisai (2004) found the Thai government’s resolve to issue a sophisticated national identity card to her citizens could create socio-economic challenges including marginalisation of migrant workers; discrimination against unlettered citizens, refugees, and minority groups such as people of the Hill tribe. The author noted access to basic and essential services by the foregoing category of people in Thailand could be a challenge owing to the introduction of an electronic identity card which captures sensitive data of all registrants.

Challenges of National ID System to the Ghanaian Economy

Success story of the national identification system in Ghana is likely to be marred by a number of challenges, including limited funding and untimely release of funds for its day-to-day operations, projects and investments. For instance, in 2007, a French government budgetary allocation of GH¢30 million for the national identification exercise was not released by the Ghanaian government to the National Identification Authority. Similarly, in 2014, the NIA requested for GH¢13,076,467.60 to settle outstanding bills of GH¢4,288,737.46 and to meet other financial needs. However, only GH¢760,000, representing about 5.8% of the total request was released to the National Identification Authority. Generally, release of funds to the National Identification Authority for capital expenditure and investment in prior periods was a challenge.

Akin to the above may be difficulties in identifying sustainable sources of funding for the national identification exercise in the medium- and long-term. There may be difficulty in ensuring the estimated over 15 million Ghanaians are duly registered and presented with national identity cards within a limited time frame as envisaged. Indeed, issuance of instant digital or electronic cards to all citizens throughout the country within a three-month period may be very challenging, if the requisite logistics are not adequately provided and deployed to designated areas on time.

Success of the registration process may be marred by inability to ensure effective deduplication and quality assurance processes to avoid rejection of valuable data. The foregoing may be a major setback to the National Identification Authority. Further, harmonisation and alignment of multiple forms of identification programmes funded by different agencies may be a hurdle for NIA. Another challenge may be the likelihood to precede system installation and staff training with citizens’ data collection. In the past, system installation and staff training were completed three years after data had been collected from the field.

Security breaches by some staff members and hackers may be a major challenge to the National Identification Authority. That is, protection of citizens’ right, privacy and sensitive information may be threatened by system intruders – unauthorised internal and external users of citizens’ information. The implementation process may be affected by the tendency to collect poor data from the field resulting in waste of limited financial resources. For instance, it turned out from the previous exercise that parts of the data collected from the then Northern region for the identification system were rejected. Another impeding factor is the fear of abuse of power by government functionaries. Unfettered access to citizens’ information may allow some political officials to exact vengeance on other citizens; or subject some innocent citizens to constant harassment, sabotage or victimisation.

Benefits of National ID System to Ghana’s Economy

The government’s decision to adapt, install and implement a national identification system comes with a number of socio-economic benefits to the country. Notable among these include ensuring integration of systems across government ministries, departments, and agencies to help avoid duplication of data and programmes; improving health coverage and overall health service delivery; ensuring government social intervention programmes such as the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) benefits go directly to targeted beneficiaries; ensuring an improvement in the dispatch of relief items by the National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO) to flood and flood-related victims; making sure government subsidies are provided for targeted recipients; and improving customer identification system for rapid loan processing and approval by various financial institutions.

Further, it would improve the country’s population estimates for essential national planning and development; enable voters to exercise their voting franchise with relative ease since the Electoral Commission can rely heavily on the National Identification Authority’s authentic data for direct registration and voting purposes; fairly estimate the number of migrants in the country; ensure efficient allocation and utilisation of the nation’s limited natural, financial and human capital resources; enhance the accuracy and reliability of data churned out by the Ghana Statistical Service and other government agencies for present and future policy formulation and implementation; harmonise government structures and systems for effective co-ordination and governing process; and ensure rapid provision of key infrastructural facilities leading to economic development and growth.

Also, the scheme is expected to facilitate the analysis of teething and lasting problems and proffering of appropriate solutions; provide a national identity card that would serve as a de facto social security card as it pertains in other jurisdictions; increase the number of citizens with identification cards; provide efficient and effective services at the national level; and assist the government to realise the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 16.9, which states inter alia: “By 2030, [each country shall] provide legal identity for all, including birth registration.”

Finally, the government is expected to implement a system that provides unique identification that is biometrically secure and aids in the provision of wide range of useful services for the underserved consumers in the areas of education, health, and financial services. These services would be on an integrated platform that brings all citizens together in a seamless manner; a system that serves as a substitute for a passport in domestic airline travels; install an effective system that would lead to seamless interconnectivity of various management systems for strong electronic commerce (e-commerce) and electronic governance (e-governance) in the Ghanaian economy.

Author’s Note

The above write-up was extracted from an earlier publication entitled: “Formalizing Ghana’s Economy through an Implementation of National Identification System: Issues and Perspectives” by Ashley et al. (2019) in the International Journal of Innovative Research and Development

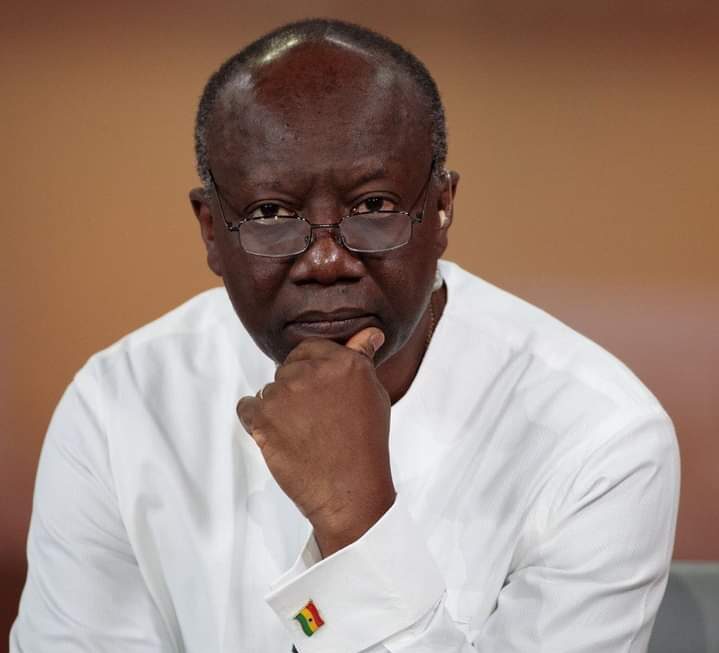

Ebenezer Ashley (PhD),

Chartered Economist/

Business Consultant.

Bibliography

Akrofi-Larbi, R. (2015). Challenges of national identification in Ghana. Information and

Knowledge Management, 5(4), 42-46.

Al-Khouri, A. M. (n.d.). Facing the challenge of enrolment in national ID schemes. Emirates

Identity Authority, 13-28.

Ashley, E. M., Takyi, H., & Obeng, B. (2016). Research Methods: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Scientific Inquiry. Accra: The Advent Press.

Clarke, R. (1994). Human identification in information systems: Management challenges and

public policy issues. Information Technology & People, 7(4), 6-37.

Combet, E. (2004). The key to ID cards: “Identity card usages,” not “identity usages.” Oxford

International Institute, 3(1).

Davies, S. (n.d.). Identity cards: Strategy, implementation &challenges. Privacy International.

Davies, S., Hosein, I., & Whitley, E. A. (2005). An assessment of the UK identity cards bills and its implications. London: LSE Research Online.

Digital Impact Alliance. (2017). Taking pragmatic steps to advance national ID efforts for development. Retrieved from https://digitalimpactalliance.org/taking-pragmatic-steps-advance-national-id-efforts-development/

Dotse, H. (2017). National ID; data security, privacy and our civil liberties! Retrieved from http://starrfmonline.com/2017/07/16/national-id-data-security-privacy-and-our-civil-liberties/

European Commission. (2006). E-ID in Estonia. Retrieved from http://www.epractice.eu/files/documents/cases/191-1170255573.pdf

Fussell, G. (2004). Genocide and group classification on national ID cards. In C. Watner and W. McElory (Eds.). National identification systems: Essays in opposition. (pp. 55-69). Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Ghanaweb.com. (2007). National identification system and its importance. Retrieved from https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/National-Identification-System-and-it-s-importance-121391.

Ghanaweb.com. (2017). Features of Ghana Card. Retrieved from https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Only-the-GhanaCard-will-confirm-your-identity-as-Ghanaian-Prof-Ken-Attafuah-581710.

Hornung, G., & Robnagel, A. (2010). An ID card for the internet-The new German card with

“electronic proof of identity.” Computer, Law & Security Review, 26(2), 151-157.

House of Commons. (2005). Identity cards bill. Retrieved from

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200506/cmbills/009/2006009.pdf

Islam, M. R., Baniamin, H. M., & Rajib, M. S. U. (2012). Institutional mechanism of national

identification card: Bangladesh experience. Public Policy and Administration Research, 2(2), 1-13.

ITU. (2016). Review of national identity programs. Geneva: International telecommunication

Union (ITU). Retrieved from https://www.google.com/search?

Jacobsen, E. K. U. (2012). Unique identification: Inclusion and surveillance in the Indian

biometric assemblage. Security Dialogue, 43(5), 457-474.

Khan, A. R. (2018). National identity card: Opportunities and threats. Journal of Asian

Research, 2(2), 78

Kitiyadisai, K. (2004). Smart ID card in Thailand from a Buddhist perspective. MANUSYA:

Journal of Humanities (Special issue), 8, 37-45.

Krupp, A., Rathgeb, C., & Busch, C. (2013). Social acceptance of biometric technologies in

Germany: A Survey. In A. Bromme, & C. Busch (Eds.). Proceeding of 2013 International Conference of the BIOSIG Special Interest Group (BIOSIG) (pp. 193-200).

Kwiringira, S. (2017). Integration of services with the national identification system, Uganda’s

case. National Identification and Registration Authority.

Lyon, D. (2009). Identifying citizens: ID cards as surveillance. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Michael, K, & Michael, M. G. (2006). Historical lessons on ID technology and the consequences

of an unchecked trajectory. Prometheus, 24(4), 365-377.

Milberry, K., & Parsons, C. (2013). A national ID card by stealth? The BC services card privacy

risks, opportunities and alternatives. Vancouver: BC Civil Liberties Association.

National Identification Authority. (2014). Ghana NIA’s legal mandate. National Identification

Authority.

Neyland, D. (2009). Who’s who? The biometric future and the politics of identity. European

Journal of Criminology, 6(2), 135-155.

NIA. (n.d.a). L2111 National Identity Register Act 2008 (Act 750)-National Identification

Authority. Retrieved from https://www.nia.gov.gh.

NIA. (n.d.b). Our history-NIA-National Identification Authority. Retrieved from

https://www.nia.gov.gh.

NIA. (n.d.c). Privacy policy-NIA-National Identification Authority. Retrieved from

https://www.nia.gov.gh.

Petermann, T., Sauter, A., & Scherz, C. (2006). Biometrics and the borders – The challenges of a

political technology. International Review of Law, Computers and Technology, 20(1&2), 149-166

Refworld. (2006). Ghana: Act No. 707 of 2006, National Identification Authority Act. Retrieved

from https://www.refworld.org/docid/548edfa94.html

Refworld. (2008). Ghana: Act No. 750 of 2008, National Identity Register Act.

Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?docid=548ee10b4

Rule, J. B. (2005). Time to ask questions about the paths opened by ID cards. Oxford: Oxford

Internet Institute.

Smith, A. D. (2008). The benefits and risks of national identification programme. Retrieved from

http://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/learning/mamagement_thinking/articles/pdf/

Soltani, F., & Yusof, M. A. (2012). Concept of security in the theoretical approaches. Research

Journal of International Studies, 1. ISSN: 1453-212X

Sullivan, C. L. (2011). Digital identity: The emergent legal concept. Adelaide: University of

Adelaide Press.

The World Bank Group. (2017). Identification for development (ID4D). Retrieved from

http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/id4d#1.

Whitley, E. A. & Hosein, G. (2010). Global identity policies and technology: Do we understand

the question? Global Policy, 1(2), 209-215.

World Population Review. (2019). 2019 world population by country. Retrieved from

http://worldpopulationreview.com/

Zoleta, V. (2018). National ID system in the Philippines: The good and the bad. Retrieved from

www.moneymax.ph

Apexnewsgh.com/Ghana/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

Please contact Apexnewsgh.com on email apexnewsgh@gmail.com for your credible news publications