Documentary by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

In the heart of Ghana’s bustling towns and quiet villages, a silent crisis unfolds. Hidden beneath the laughter, ambition, and dreams of the youth, a menace grows, one that threatens not only their futures but the very soul of communities. This is the story of how drug abuse is quietly ravaging the lives of young people, pulling them into a spiral of addiction and despair before their dreams can ever take flight.

Felix was once like any other young man, full of hope, with a family that cherished him and a classroom that held the promise of a better future. But somewhere along the way, his path darkened. Drugs became his companion, and soon, he found himself wandering the streets, trading textbooks for a haze of addiction.

He remembers the day it all started. “When I was in JHS3, it was when I travelled to Kumasi. That’s when I started taking it,” Felix recalls, his voice heavy with regret. “I came home, then went to school. So, that’s how I entered the job.”

The “work,” as Felix calls it, is hard labor, carrying goods for others, hustling for daily survival. “If I don’t take it, I cannot work,” he admits. The drugs numb the pain, but they also sever him from his family. “Right now, I’m not close with them,” he says quietly, the weight of isolation evident in his voice.

His family knows about his addiction, but not the full extent of his trauma. “Maybe they don’t know, but I don’t know if they know or not,” he confides. For Felix, every day is a battle; he needs work, but work means drugs, and drugs mean distance from those he loves. His story is one of many, a haunting echo of how quickly and quietly hope can slip away.

Known to many as Hunu, he is a father, a son, and a man bearing the weight of choices he never meant to make. His story is marked by the invisible hand of peer pressure and the desperate search for belonging.

“Actually, there’s a challenge. A big challenge,” Hunu admits. “I’m a student, alright. However, I cannot simply tell you that this is what happened when I entered into this. It’s all about the friends you follow. Your influence.”

He speaks of how easy it is to fall in. “Someone will be there, he will not like to take it, but the moment he follows two or three people who take it, he will like to try it.” The drugs become a necessity, “The moment I wake up, I don’t take it, I will not feel alright. Not that I am sick, but I am not normal. But the moment I take it, I will get to my normal stage.”

Hunu’s reflection is a stark reminder of how easily youth can be led astray, not always by malice, but by the natural desire to fit in, to be part of something, even if it leads down a dark path.

At just 19, Aduko Jacqueline is already a mother of two. Her life, once filled with dreams, is now a daily struggle against addiction. She is honest about her pain, the stigma, and the longing for rescue.

“If I get what I want, there will be damn smoking,” she says, her words tinged with sadness. “I’m not supposed to smoke, I’m a girl, but if I always smoke, I always stink very well. I don’t have the money to do what I want, but if I get it, I will do it. I will stop smoking.”

Jacqueline’s self-awareness is heartbreaking. “As I’m sitting here, I always stink. If you only see me sitting now, without talking to anybody, I’m thinking about how to stop it. But if I don’t, it will enter me, you understand. So, unless I get someone to help me, someone behind me, so that the person will be helping me, I will increase myself so that I will stop everything and be free.”

Her plea is simple: help. “I’m praying that maybe God will help me, then I will find a job.” Jacqueline’s story is a cry for support, a call to action for communities to rally around those who are struggling before they are lost.

Baba, known in the ghetto as Starboy, is in his twenties but has already lived a lifetime in the shadows of addiction. His drug of choice is weed, and for him, it is not just a habit; it is a lifeline.

“Weed is my life. And weed is the one that can help me with everything that I need in my life,” he shares. “If I smoke this weed… It’s really good for me. If I think of doing something bad, when I take the weed, I swear to God, I always think it’s good.”

Baba’s family has long known of his addiction. “I’ve only let them understand that I’m a weed smoker. And the weeds are killing me, what I have, but what I feel happy about. Because if I smoke the weed, I feel so great.”

He started young, just ten years old. Now, he says, “It gives me a lot of health. It gives me a lot of pressure, a lot of things that I can’t handle myself very well.”

For Baba, the addiction is both a curse and a comfort, a chain he cannot break but one that gives him a fleeting sense of control in a world that often feels overwhelming.

For Emmanuel, addiction is not just a personal battle; it is a family affair. “Well, I choose to smoke this because I can just say that it’s inside the blood of the family,” he says. “Your dad takes some. My uncle takes some. I’ve seen that taking this is normal to me.”

He is a young man who should be in school or working, but instead finds himself fighting an enemy that feels almost inherited. “The smoke of the weed. Due to the system’s limitations and the scarcity of job opportunities in the town. We just manage what we do for a living.”

Emmanuel’s words are a plea for understanding. “Sometimes you just have to sit and have the weed and take your mind because you need to release some stress. You’ll be thinking how to take care of the family, how to do this and that, but there’s no way.”

He is quick to defend himself and others like him. “There are some holistic people, but that’s why they think everyone who smokes is a bad person. Not everyone who smokes is a bad person. It’s because of stress that some of us smoke and lack of opportunities.”

His message to the government is clear: “Build more companies. More job opportunities. It’s not all of us that are lazy. Some of us have families to take care of. We will just try to make up our own way to also get ourselves in those jobs.”

The stories of Felix, Hunu, Jacqueline, Baba, and Emmanuel are not isolated. They are the faces behind troubling statistics. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, about 316 million people globally used drugs in 2024. The Narcotic Board of Ghana estimates that 50,000 people, most of them youth, abuse drugs in Ghana, with 35,000 being students from junior high, senior high, and tertiary institutions. The northern regions account for more than half of these cases.

Watch the full video here.

The consequences are devastating. Over 2.6 million people die each year worldwide as a result of alcohol and drug abuse. Dreams of becoming doctors, nurses, and professionals are lost, replaced by the harsh reality of addiction and, for some, a bed in a psychiatric hospital. The numbers are not just statistics; they are lives interrupted, families broken, and futures rewritten

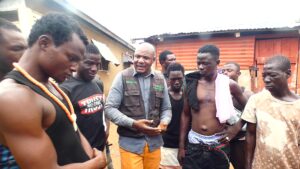

In response to these alarming trends, some are taking action. The author of this account decided to visit schools in the Upper East Region, determined to educate students about the dangers of drug abuse and the importance of focusing on their studies.

At Zamse Senior High Technical School, he addressed a group of students: “Most of the youth today have actually used alcohol to destroy themselves. Some of them wanted to be doctors, and some of them wanted to be nurses. Today are at home, and some of them are at the psychiatric hospital. Because that dream has been shattered. Because of alcohol and drug abuse.”

He shared sobering statistics, emphasizing that over 2.6 million people die annually from alcohol and drug abuse, and urged students to “shy away from alcohol… because your life is important to us. Your life is important to this country.”

The campaign continued at Bogatanga Senior High, where students were encouraged not only to avoid drugs themselves but to support their peers in doing the same. “Let us take it into practice. Let us abide to it. And I am sure we will all achieve our dream,” one student responded.

The crisis has drawn the attention of community leaders, health professionals, and traditional authorities. Upper East Youth Association President Adingo Francis is passionate about the need for collective action: “Substance abuse is actually a major, major social canker… That has to do with the chiefs, opinion leaders, assembly members, you and I, the law enforcement agency.”

He draws a parallel with the fight against illegal mining (GALAMSEY), arguing that protecting the youth is just as important as protecting the environment.

“It pierces the heart of parents to see you give birth, raise a child up, send a child to school, and he eventually becomes a dropout or gets addicted to drugs. And you just don’t know what to do. It’s painful, and parents are crying day in, day out for us as a nation to see how we can deal with this canker once and for all.”

Dr. Brahma Baba Abubakari, Upper East Regional Director of Ghana Health Service, warns that the crisis is escalating. “The issue of substance abuse is not a new thing, just that it has escalated beyond our imagination in these times. If you look at the age range… that is more frightening because you have people as young as 13, 14 years being engaged in this.”

He reveals that even health professionals are not immune. “We even have some of our professionals who get engaged in this during their stay in the training institutions… And that is why these days the complaints about the attitude of staff have increased. So I think we need to look at it again, both the regulatory authorities and the managers in the region, to see how we can regulate these things.”

Efforts to combat addiction extend beyond education and regulation. At the regional health directorate, the mental health coordinator describes the growing prevalence of substances like tramadol, cannabis, shisha, and energy drinks among the youth.

“Now, most of them are also getting addicted to energy drinks. Some of them don’t see it to be a psychoactive substance. They see it to be a normal drink they are taking. But eventually they get addicted to it and they are not even aware.”

The coordinator offers a message of hope: “If you find yourself addicted to any of these substances… we are here to help you. You can walk into our unit here at the regional health directorate, and we will now direct you to the appropriate places to go for help.”

At the Presbyterian Psychiatric Hospital in Bogatanga, Dr. Dennis Domasang-Daliri explains how they assess and treat patients admitted for substance abuse. “For most people who are brought into the facility on account of substance abuse… we will normally take them through some sort of assessment… There is no way we are going to manage such a person without managing the substance problem, which is actually supposed to be the big one.”

Traditional leaders are also stepping up. The President of the Upper East Regional House of Chiefs notes that social gatherings are often opportunities for youth to indulge in drugs. He supports the introduction of bylaws to regulate such behavior and the use of substances like tramadol.

“We want the best for our children. We want the best for our citizens,” he says, calling for close collaboration between traditional authorities and district assemblies.

The Food and Drugs Authority, under the Public Health Act 851 of 2012, is tasked with safeguarding public health by regulating the entry and exit of products and ensuring quality standards. Mr. Ndego Ebel, Upper East Regional Director, emphasizes the vigilance of the Authority in monitoring ports and borders to prevent substandard or adulterated drugs from entering the country.

“We have officers assigned to ensure that all products that are under our regulation, coming in and out of the country, meet their needed regulatory standards. Because of our presence, it is usually very difficult for substandard medications or any adulterated regulatory products from coming into the country.”

The National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE) plays a vital role in sensitizing the public. Augustine Akugre, Deputy Regional Director, highlights the transformative power of education. “Some reformed drug addicts, after our education, have come clearly to talk about how the education has saved their lives, has saved the lives of their family, has saved the lives of their relations, has saved the lives of their community members.”

He points out the broader impact of addiction, noting that when a breadwinner falls into addiction, entire families and communities suffer. The NCCE’s outreach is crucial in helping youth understand the consequences of drug abuse and in supporting those on the path to recovery.

Pastor Thomas Abukari, Head Pastor of the Baptist Church and Chairman of the Christian Council in Bolgatanga, believes the media plays a role in worsening the crisis. He attributes part of the rise in youth drug and alcohol abuse to alluring advertisements on television, which normalize and glamorize substances.

This highlights the need for responsible media practices and stronger regulations on advertising, especially those targeting young audiences who are most susceptible to influence.

The stories of Felix, Hunu, Jacqueline, Baba, and Emmanuel are the stories of countless others whose voices may never be heard. Their struggles are real, their pain profound, and their futures uncertain. But their stories also serve as a call to action.

Combating the scourge of drug abuse will require a united effort, from government to communities, from educators to health professionals, from traditional leaders to the youth themselves. It means creating opportunities, providing support, enforcing regulations, and above all, extending compassion to those caught in the grip of addiction.

The future of Ghana depends on the strength of its youth. By shining a light on this silent crisis, by listening to the stories behind the statistics, and by working together as a nation, there is hope that shattered dreams can be rebuilt and that the next generation can rise, free from the chains of addiction.

It is often said that the youth are the leaders of tomorrow. In the Upper East and across Ghana, the resilience of young people remains unbroken, even as they face immense challenges. With collective diligence, empathy, and action, there is hope that the silent crisis will give way to a new dawn, a future where every young person has the chance to dream, strive, and succeed.

Source: Apexnewsgh.com

Email: apexnewsgh@gmail.com