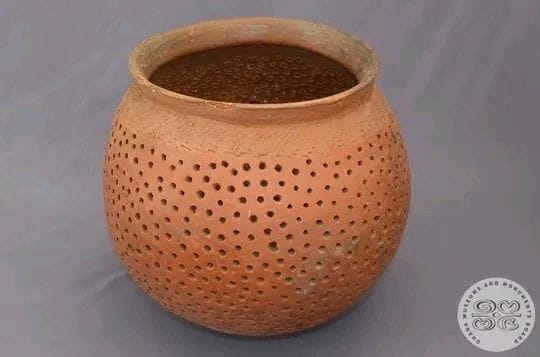

At first glance, the perforated clay pot appears ordinary—humble inform, earthy in colour, and practical in purpose.

Yet within its carefully shaped body and evenly spaced holes lies a deep story of Gurensi indigenous knowledge, environmental intelligence, and cultural continuity. This vessel, handcrafted using the coiling method and hardened through open firing, is not merely a kitchen implement. It is a quiet archive of lived experience, ancestral science, and everyday creativity that has sustained Gurensi households for generations.

Among the Gurensi people of northern Ghana, pottery has long been more than a craft. It is a way of knowing the land, interpreting the environment, and responding intelligently to daily life. Clay is not seen simply as raw material; it is understood as part of the earth’s living substance. Women—traditionally the custodians of pottery knowledge—know where to find the right clay deposits, often along riverbanks or low-lying areas where the soil holds moisture and fine particles. The selection of clay is guided by touch, colour, and experience passed down through observation rather than formal instruction.

Once collected, the clay is prepared with care—cleaned of stones, kneaded, and tempered to prevent cracking. The shaping of the pot is done using the coiling method, an ancient technique that requires patience and precision. Thin rolls of clay are laid one upon another, gradually forming the walls of the vessel. Each coil is blended smoothly into the next by hand, allowing the potter to control thickness, balance, and strength. This process reflects the Gurensi approach to knowledge itself—built slowly, layered carefully, and refined through repetition.

In Gurensi communities, pottery knowledge is often transmitted informally, from mother to daughter, aunt to niece, or elder to apprentice. Learning happens through watching, assisting, and doing. There are no written manuals, yet the consistency of form and function across generations speaks to a highly effective system of knowledge transfer. The pot becomes a record of that learning process, carrying within it the gestures and decisions of the hands that made it.

After shaping, the pot is left to dry gradually in shaded areas, protected from harsh sunlight that could cause cracking. When ready, it is fired in the open using firewood, grass, and organic matter

gathered from the surroundings. Open firing is both an art and a science. The potter must understand heat, airflow, and timing, even without thermometers or kilns. The reddish-brown colour that emerges after firing is the result of iron-rich clay reacting with oxygen, a

transformation well understood through generations of practice.

This firing process is deeply symbolic within Gurensi cosmology. Fire is associated with transformation, endurance, and renewal. The pot enters the fire fragile and emerges resilient, ready to serve. In this way, the vessel mirrors human life—shaped by experience, tested by

hardship, and strengthened through endurance.

The defining feature of this particular pot is its perforated surface. The holes are carefully spaced and deliberately sized, designed to allow water to drain efficiently while retaining grains, beans, or vegetables. Before the arrival of plastic sieves or metal colanders, Gurensi households relied on such pottery for washing millet, sorghum, rice, bambara beans, and leafy vegetables. The design demonstrates an intuitive understanding of water flow, gravity, and material strength.

This is indigenous engineering in its most practical form. The pot solves a daily problem using locally available materials, without waste or excess. It requires no external energy, no imported

components, and no replacement parts. When it breaks, it returns harmlessly to the earth. In today’s language, it is entirely sustainable.

Beyond its function, the perforated clay pot occupies a central place in Gurensi domestic life. Food preparation is rarely a solitary act. Washing grains or vegetables often takes place in shared spaces—courtyards or shaded areas—where women exchange news, pass on advice, and reinforce social bonds. The pot is present during these interactions, quietly woven into the rhythm of community life.

Such objects also carry memory. A pot may remind a woman of her mother, who taught her to cook, or a grandmother who shaped similar vessels decades earlier. Even when replaced or repaired, the form remains familiar, reinforcing continuity amid change. In this way, the pot becomes a bridge between generations.

From a technological perspective, the vessel challenges narrow definitions of innovation. It demonstrates applied scientific principles developed through observation and long-term

experimentation. The Gurensi potter may not use academic terminology, yet her understanding of material behaviour, heat dynamics, and structural balance is no less sophisticated. This is science embeddedin culture, practiced daily and refined over centuries.

Unfortunately, such knowledge systems are increasingly threatened. Industrial kitchenware, imported goods, and changing lifestyles have reduced reliance on traditional pottery. Younger generations may associate clay pots with hardship or view them as obsolete. As elders

pass away without apprentices, valuable skills risk disappearing. The loss would extend beyond the object itself. It would mean the erosion of a worldview that values patience, environmental harmony, and community-based knowledge. Preserving Gurensi pottery traditions therefore requires more than museum display. It demands documentation, education, and active transmission of skills within communities.

Cultural institutions, schools, and development planners have a role to play. By recognising indigenous technologies as valid and valuable, they can help restore pride in traditional crafts. Supporting potters through training, market access, and cultural tourism can turn

heritage into livelihood without stripping it of meaning.

Today, as the world searches for sustainable alternatives and locally grounded solutions, the perforated Gurensi clay pot offers quiet but powerful lessons. It shows that innovation does not always require complexity, that technology can be rooted in care for the environment, and that everyday objects can carry deep cultural intelligence.

What appears to be a simple kitchen tool is, in truth, a material expression of Gurensi identity. It tells a story of women’s knowledge, environmental adaptation, and continuity in the face of change. It reminds us that heritage does not reside only in monuments or festivals, but also in the tools that have fed families, sustained communities, and shaped daily life.

So when we encounter this perforated clay pot—whether in a household, a museum, or a photograph—we are not merely looking at clay shaped by fire. We are witnessing a living tradition, a conversation between past and present, and a testament to the enduring wisdom of the

Gurensi people.

Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Prosper Adankai/Contributor