Long before electricity reached the villages of Northern Ghana, long before refrigerators hummed in kitchens, communities discovered a simple, sustainable, and ingenious way to keep water refreshingly cool: the clay pot. Among the Gurensi people, as with other northern communities, the clay pot was not only a household necessity; it was a symbol of practical wisdom, scientific observation, and deep knowledge of the natural environment.

It demonstrates how technology does not always need circuits, motors, or complex machinery. Sometimes, it is about listening to the earth, understanding its properties, and working in harmony with nature.

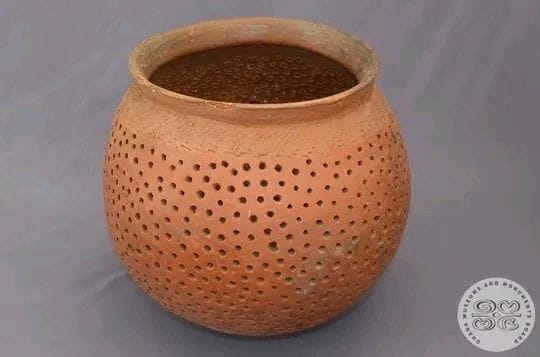

These clay vessels are crafted from local earth, carefully selected by the potters for its particular qualities. In many cases, the clay is mixed with kaolin, a fine white clay that lends the vessel strength while retaining microscopic porosity. This porosity is the secret behind the clay pot’s cooling ability. Even after firing in open pits or small kilns, the walls of the pot remain slightly porous, capable of allowing tiny amounts of water to seep through to the surface. When

These droplets reach the outer surface of the pot, they begin to evaporate, carrying away heat and leaving the remaining water inside noticeably cooler.

For the Gurensi, the creation of these pots is a craft learned over generations, passed from mother to daughter, aunt to niece, and sometimes from elder potters to apprentices.

There are no written

manuals, no textbooks; the knowledge is tacit, embedded in gestures, rhythms, and careful observation. The potter kneads the clay, feeling its texture and consistency, shaping the vessel by hand using traditional techniques such as coiling or pinching. The form is guided

by both utility and aesthetic preference. Some pots are simple and functional, designed for storing and cooling water. Others are decorated with incised patterns, geometric motifs, or symbolic shapes reflecting personal taste, family identity, and cultural expression.

The cooling process itself is a marvel of indigenous science. As water slowly seeps through the walls, it evaporates into the air. This phase change—from liquid to vapor—requires energy, and this energy is drawn from the water inside the pot and the surrounding clay walls. The effect is immediate: the water temperature drops, providing refreshment that seems almost magical to those unfamiliar with the principle.

In essence, the clay pot operates as a natural refrigerator, a technology powered entirely by the sun, air, and earth. The kaolin mixed into the clay enhances this process. Its mineral structure makes the walls fine-grained and durable, yet still porous enough to allow controlled evaporation. The result is a vessel that cools effectively while remaining long-lasting and resilient under daily use.

The “cold taste” of water drawn from a clay pot is not magic—it is physics in action, observed and applied by generations of Gurensi people long before formal science documented it. In a region where the dry season brings soaring temperatures, often exceeding forty degrees Celsius, the simple clay pot is a lifesaver. It provides hydration, preserves health, and supports the demanding daily routines of farming, herding, and household work. Its value is both practical and cultural, connecting people to their environment in an intimate, interactive way.

Crafting a clay pot requires more than technical skill; it demands patience, intuition, and a deep understanding of natural materials. The potter must know when the clay has reached the right consistency, how thick the walls should be, and how to shape the opening for optimal use. During firing, the potter controls the heat by adjusting the placement of wood, grass, and other combustible materials, ensuring that the vessel does not crack and that the kaolin’s properties are preserved. Firing is as much an art as a science, requiring keen observation, timing, and experience. The reddish-brown colour that emerges is a signature of the firing process, indicating the pot is ready for everyday use.

Beyond their scientific function, these clay vessels carry deep cultural significance. They are central to household life and communal activities. In many Gurensi homes, clay pots stand in the compound, shaded under a tree or placed on a raised platform to keep the water clean. They are used during communal gatherings, ceremonies, and festivals, serving both practical and symbolic roles. A well-made pot signals skill, care, and attentiveness to household needs, while also

representing the continuity of cultural knowledge and craftsmanship. Through such objects, the everyday lives of the Gurensi are linked to generations past, connecting present households to their ancestors in an unbroken chain of practice and understanding.

The artistry of the clay pot is also significant. Many pots are decorated with simple incised lines, grooves, or textured patterns. These designs are more than decorative—they often carry symbolic

meaning, reflecting local cosmologies, agricultural cycles, or community identity. Women, who are traditionally responsible for decoration and finishing, use these designs to express creativity,

communicate status, and reinforce social norms. The decorated vessel becomes a living canvas, a medium through which cultural narratives are inscribed onto functional objects. The clay pot is also an example of sustainable technology. Unlike modern appliances, it requires no electricity, no refrigeration, and no synthetic materials. When a pot eventually breaks or reaches the end of its life, it returns to the earth without polluting it. Its production and use exemplify a closed-loop system, one that minimizes waste and harmonizes with the natural environment. In this respect,

the clay pot offers lessons for contemporary discussions on sustainability, climate adaptation, and low-impact technologies. It is an object that embodies ecological intelligence embedded in cultural

practice.

The process of using the pot is equally instructive. Water is poured in, allowed to settle, and gradually cooled by evaporation. There is a rhythm to its use, a daily interaction that teaches observation, patience, and respect for natural processes. Children grow up understanding how the pot works, not through formal instruction but by participating in its care and use. They learn that simple materials can achieve complex results, that nature can be a partner in human comfort, and that technology can be both functional and beautiful.

Interestingly, the clay pot also plays a role in local identity and pride. Visitors to Gurensi villages often remark on the distinctive shapes, sizes, and decoration of the vessels. Each pot tells a story

of its maker, of local material resources, and of long-standing traditions that have persisted through changing times. In this sense, the clay pot is a cultural ambassador, carrying the ingenuity and

resilience of the Gurensi people to the wider world. Modern scientific explanations have only recently caught up with what Gurensi communities have known for centuries. The principle of

evaporative cooling, the physics behind heat transfer, and the properties of kaolin were all observed empirically and applied practically by local potters. This knowledge, embedded in everyday

objects, demonstrates that indigenous science is not separate from modern science; it is a complementary understanding developed in response to real-life needs and environmental conditions.

Today, efforts are underway to document and preserve these practices, recognizing their educational, cultural, and ecological value. Museums, cultural heritage centres, and educational programmes are increasingly highlighting the clay pot as an emblem of indigenous knowledge and sustainable design. Scholars and development practitioners study the vessels not only for their functionality but also for the cultural and social systems they represent. They remind us that technology can be simple, elegant, and community-centered, and that the knowledge of local artisans has much to teach contemporary society.

The clay pot also challenges assumptions about what constitutes innovation. In a world dominated by electronic devices and mass-produced goods, these hand-crafted vessels show that high-tech solutions are not the only path to comfort and efficiency. Indigenous technologies, honed over generations, often solve problems in ways that are affordable, environmentally friendly, and socially embedded. They are a reminder that human creativity has always been inventive,

adaptive, and deeply connected to the environment.

In Northern Ghana, the everyday act of drinking cool water from a clay pot is therefore rich with meaning. It is a daily interaction with history, science, and culture. The hands that crafted the pot, the earth from which it was shaped, and the evaporative process that cools the water all come together in a single, elegant cycle of knowledge and use. To drink from such a vessel is to participate in a living tradition, one that celebrates resourcefulness, sustainability, and

community intelligence.

In this simple vessel, we find an intersection of art, science, and culture. Its shape is practical, its decoration meaningful, its function ingenious. It is a reminder that knowledge does not always

reside in textbooks or laboratories; sometimes it resides in clay, in fire, in the patient observation of nature, and in the careful hands of a potter. The clay pot is a bridge across time, connecting

generations of Gurensi households to the natural world and to one another.

As modern technologies become more pervasive, the clay pot continues to teach lessons in sustainability, adaptation, and the intelligent use of local resources. It shows that innovation is not always about complexity; it is about understanding the materials at hand and working harmoniously with them. The principles embedded in these vessels—evaporation, thermal regulation, and material selection—are timeless, demonstrating that indigenous knowledge systems can provide solutions that are relevant even in contemporary contexts.

Ultimately, the clay pot is more than an object. It is a testament to human ingenuity, environmental awareness, and cultural continuity. In the arid and hot landscapes of Northern Ghana, it stands as a daily companion, a functional work of art, and a silent teacher. Through it, the Gurensi people demonstrate how thoughtful engagement with nature, careful observation, and generational knowledge can produce tools that are both practical and elegant, sustainable and sophisticated.

The next time water drawn from a clay pot feels refreshingly cool, it is worth pausing to consider the centuries of observation, experimentation, and craftsmanship behind it. This is indigenous

science in its purest form—simple, effective, and beautiful. It is a technology that honors the earth, supports the community, and sustains life. In a single vessel, the past meets the present, and in that

meeting, the wisdom of the Gurensi people continues to flow, just like the cool water it preserves.

Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Prosper Adankai/Contributor