Newly Posted Teachers Give GES One-Month Ultimatum Over Delayed Staff IDs, Unpaid Salaries

A wave of frustration swept through the Ghana Education Service (GES) headquarters on Wednesday, February 18, as the 2024 batch of newly posted teachers staged a picket to demand urgent action over months of unpaid salaries and the delayed issuance of staff IDs. The group, who have been teaching in schools across the country since 2024, is calling on the GES to resolve these issues within one month or face “drastic action.” For many of the teachers, the situation has become dire. Some have not been paid for 12 months, others for as long as 14 months, despite having received financial clearance and diligently working in their assigned schools. The teachers say their documents, which district and regional authorities claimed were submitted, have gone missing at the national office, leaving them in limbo. Speaking to the media, Daniel Aidoo, the convenor for the group, voiced the collective frustration: “All that we are demanding is that they give us our staff IDs and acknowledge us as teachers employed by the Ministry of Education and the Ghana Education Service. We don’t want any back and forth. Whosoever is responsible for the issuance of our IDs should be held accountable.” The teachers are adamant that this cycle of delay and neglect should not be allowed to continue, warning that future batches should not have to endure the same ordeal. They have given the GES a one-month deadline to resolve the issue, stressing that if there is no progress, they will escalate their actions in pursuit of justice and recognition. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

President Mahama Pledges Two Million Desks for Basic Schools by 2026

President John Dramani Mahama has unveiled an ambitious plan to supply two million desks to Ghanaian basic schools by the end of 2026, a move set to dramatically improve learning conditions for students across the country. The announcement came during his address to the Ghanaian community in Zambia on Thursday, February 5, as part of his three-day state visit. President Mahama highlighted the chronic neglect of basic school infrastructure, revealing that approximately 1.2 million children currently attend classes without desks. “The basic school level has been neglected. The previous government focused mainly on SHS because of its flagship Free SHS program. Many basic schools lack textbooks and furniture, and you often find children sitting on the floor,” he remarked. He assured the community that the government is determined to tackle the problem head-on. “This year, we are going to provide two million school furnishings. By 2028, no Ghanaian pupil will have to sit on the floor to study,” President Mahama pledged. The announcement has been widely welcomed by education stakeholders. Kofi Asare, Executive Director of Africa Education Watch, commended the government for prioritising student comfort and called for swift implementation. “We hope that the desks will arrive soon because this is long overdue,” he said. The pledge marks a significant step toward bridging infrastructure gaps in Ghana’s basic education sector and ensuring that every child has a comfortable and dignified environment in which to learn. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

President Mahama Orders NIB Probe Into Alleged Sale of Overseas Scholarships

President John Dramani Mahama has ordered the National Investigation Bureau (NIB) to launch an immediate investigation into allegations of malpractice in the award of overseas scholarships, following claims made during a radio programme. In a directive dated February 3, 2026, and addressed to the NIB’s Director-General, Government Spokesperson Felix Kwakye Ofosu, MP, stated that the President’s attention was drawn to comments aired on Sompa 106.5 FM. During the Twi-language broadcast, panellist and former CEO of the National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Programme, Mr. Kofi Ofosu Nkansah, alleged that an individual had paid money to secure a scholarship to study abroad. The President described the accusation as serious and of significant public interest, especially in light of his administration’s commitment to transparency, integrity, and equitable access to education. The directive instructs the NIB to investigate the claims without delay, establish the facts, identify any individuals involved, and assess the credibility of the allegations. The Bureau has also been tasked with submitting its findings to the President for review and any subsequent action deemed necessary. The official communication was signed by Mr. Kwakye Ofosu on behalf of President Mahama. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

Scholarship Authority Boss Backs Mahama’s Probe into Alleged Sale of State Scholarships

The Director-General of the Ghana Scholarship Authority, Mr. Alex Asafo Agyei, has thrown his support behind President John Dramani Mahama’s decision to order a full-scale investigation into allegations that government scholarships were sold to politically connected individuals. The investigation was triggered by claims made by former government official Kofi Ofosu Nkansah, who alleged during a radio interview that scholarships meant for Ghanaian students were sold to members of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and others for studies in the United Kingdom. In response, President Mahama has tasked the National Investigation Bureau (NIB) to conduct a comprehensive inquiry into the matter. In a statement issued on Tuesday, January 3, Mr. Agyei described President Mahama’s move as necessary and timely, stressing the importance of protecting the credibility of Ghana’s scholarship system. He firmly rejected allegations linking the Scholarship Authority to such deals, explaining that under his watch, no scholarship had been granted for studies in the UK. “For instance, if you take the Ghana Scholarship Authority, under my leadership as Director-General, not a single scholarship award has been made for anyone to study in the United Kingdom, as he alludes. This position has been well communicated to institutions in the UK,” he emphasized. Mr. Agyei also criticized the previous administration, alleging that the scholarship scheme was marred by irregularities, including the issuance of “fake awards” by the former Registrar as recently as March 2025. He highlighted that the current administration has enacted reforms to restore fairness, transparency, and merit to the scholarship process, with a zero-tolerance stance on corruption and political favoritism. “The era where the rich, connected and influential cornered scholarships outside merit is over,” Mr. Agyei declared, pledging the government’s ongoing commitment to accountability. He assured the public that any wrongdoing uncovered by the NIB’s investigation would be met with decisive action, adding, “For every act of plunder perpetrated against the nation, full accountability will be demanded, and the time for reckoning is fast approaching.” The NIB probe is expected to verify the claims and recommend appropriate measures to safeguard the integrity of state-sponsored scholarships.

The Broken Chalkboards: Upper East Peace Council Chair Decries Rising Student Riots

Alhaji Sumaila Issaka, Chairman of the Upper East Regional Peace Council, has voiced grave concern over the growing trend of student riots in the region, a worrying development he believes is fast becoming a destructive norm among secondary schools. In a recent interview for the documentary “The Broken Chalkboards,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen for Apexnewsgh, Alhaji Issaka laid bare the scale of the problem and the urgent need for dialogue and reform. “It’s been a very difficult situation in this region, especially the way this rioting has been going on. It’s now like a canker and so contagious. The moment Zamstech demonstrates, the next day Gowrie is demonstrating, the next day Bongo is demonstrating, the next day Big Boss, and then on and on,” Alhaji Issaka lamented. He noted that while older institutions such as Navrongo Senior High School, Notre Dame, and Bawku Senior High School, as well as the training colleges, where students are considered adults, rarely report such incidents, the wave of unrest continues unabated among the newer institutions. “What I personally don’t understand is why these demonstrations, when you have an SRC that can present your grievances to the authorities,” he added, underlining his bewilderment at the preference for destructive protest over dialogue. Kindly watch the full video here: https://youtu.be/GSQR3-T6EaE. The Peace Council, Alhaji Issaka revealed, had previously initiated peace clubs in several schools as a proactive measure to curb the violence. However, these efforts were hamstrung by a lack of funding, making it impossible to sustain regular outreach. “It’s been of great disturbance to us, especially the destruction on the campuses,” he said, noting the heartbreak of seeing already scarce resources in one of Ghana’s poorest regions destroyed by students themselves. He recalled, “They will not pass Presec or Achimota and give us a bus here if the supplies are very few. Yet we continue to destroy the few that we have. When we went to school, we didn’t demonstrate, but now it’s like they are so proud of it.” Alhaji Issaka expressed his frustration at the often trivial reasons for these demonstrations. “Most of the time they are so flimsy, so annoying that you cannot tolerate them,” he said. He cited the example of students at Gowrie Senior High School insisting on shower facilities despite vandalizing existing ones, and then demanding the dismissal of the headmistress when standpipes were provided instead. In other cases, students ignored bans on personal electronic devices and overloaded dormitory sockets, leading to repeated fires and costly repairs, only to protest when precautionary measures were implemented. “What bothers me most is that the reasons are so flimsy. And if that is even the case, must you go and damage the property of the school? Then you keep complaining, we don’t have this, we don’t have that,” he said. He recounted students insisting on using coal pots for science practicals instead of the safer Bunsen burners of his own school days, and the paradox of demanding better conditions while destroying what little is available. The recurring destruction, Alhaji Issaka noted, ultimately impacts innocent parents who are forced to pay for damages. “After every investigation, money will be paid. And this money will come from the parents,” he explained, recounting a personal experience at Senegal Senior High, where burned motorbikes had to be replaced, ironically benefitting some teachers but compounding hardship for families. Another disturbing trend is the rise of tribalism in school leadership, a stark contrast to the diversity and harmony of past decades. “To the extent that, if you are not a Kassena-speaking boy, you cannot be Senior Prefect in Navrongo Secondary School. If you are not a Guruni speaking boy, you can’t be the Senior Prefect of Big Boss, Tongo Senior High School. If you are not a Kusasi-speaking boy, you cannot be a Senior Prefect of Bawku Secondary School. Why? So this is what is happening? Even though they are extending it to their heads, insisting that if you are not from that area, you shouldn’t be a head. Really?” he asked incredulously. He reflected fondly on the past, when students and leaders from various backgrounds worked together without division, and called the current climate “a big headache.” Despite setbacks, the Peace Council is determined to revive its outreach efforts. Alhaji Issaka detailed recent and ongoing attempts to coordinate with regional education authorities and NGOs to reintroduce peace-building programs in schools. Plans are in place to divide the council into groups and visit schools across the region, fostering dialogue and conflict resolution skills among students. The council’s goal is clear: to help students understand the importance of using the SRC as a channel for grievances, rather than resorting to violence. “Let the students understand that the SRC is there to represent them at the various meetings. And if they have any grievances, they should pass them to those committee members. So that when they go, they table it,” he advised. Alhaji Issaka believes much of the unrest stems from a lack of awareness and leadership among students, and from the influence of troublemakers. He noted that simple disputes, such as the theft of a phone, which is itself contraband, can quickly escalate into widespread violence and even tribal conflict. “Two students fight, and the Bawku incident crops up. You come, and it’s your kinsman against another man, and you just join the fight.” He urged proper reporting and resolution of issues through the appropriate channels, rather than resorting to mob justice or property destruction. “If you suspect somebody, report him to the authorities. And if they search him and find your phone, they give it to you. But these fights, now, the tribal fighting is in these two schools. Which was not the case before.” Alhaji Issaka closed with an impassioned plea for a return to civility and the prioritization of dialogue, warning that continued unrest threatens not only the schools but the entire region’s progress. “We want us to grow. Yet, we are last in everything.

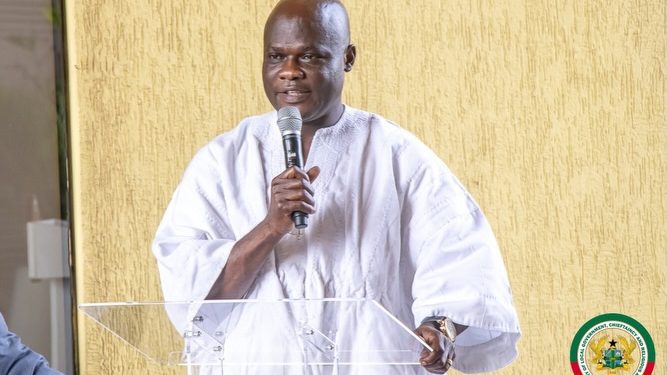

The Broken Chalkboards: Upper East Regional Minister Urges Discipline and Improved Infrastructure to Tackle School Riots

The Upper East Regional Minister, Mr. Akamugri Donatus Atanga, has expressed deep concern over the growing spate of student riots in second-cycle institutions across the region, describing the trend as “worrying and needless.” In a documentary engagement with Apexnewsgh’s Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen, the Minister recounted his personal experience since assuming office five months ago. He revealed that the wave of disturbances began under his tenure at St. Benedict’s Secondary School, where a stolen meal sparked clashes that later took on tribal undertones. “Can you steal food and be fighting? Did you steal a tribe? Can you understand that?” he asked, questioning how minor disputes were being allowed to escalate into violent confrontations. He explained that subsequent riots stemmed from issues such as stolen mobile phones, broken water systems, poor sanitation facilities, and disputes over discipline and welfare. For instance, in one case, students rioted after going days without water and being forced to fetch from nearby communities, exposing female students to safety risks. Mr. Atanga identified indiscipline and weak enforcement of school regulations as major drivers of the unrest. He lamented that rules prohibiting items like mobile phones were often flouted with the complicity of some staff. “Until all of us stand by the fact that these are the things we don’t want and we all abide by it, we will face these issues,” he said, urging teachers and school authorities to strictly enforce existing regulations. He also criticized the current disciplinary regime, which he believes has emboldened students to challenge authority. “During our time, when you committed a crime, your masters were allowed to punish you, and nobody could attack them. Today, they say nobody should punish misbehaving students. The teachers are there, but the students are running down the masters,” he noted. The Minister called for a review of disciplinary measures to restore teachers’ authority while protecting students’ rights. “Unless we get back to the drawing board and look at which offenses are punishable, we are likely to keep seeing this indiscipline,” he warned. Beyond discipline, Mr. Atanga highlighted the role of poor infrastructure in fueling discontent, particularly the lack of toilets and water facilities. He urged district assemblies to prioritize school sanitation and water provision through the Common Fund and other initiatives. “It is not proper for a secondary school to be there without a toilet facility, forcing students to share public toilets or practice open defecation. This exposes especially the girls to serious risks,” he stressed. He also cautioned against conflicts among school management and staff, noting that internal divisions often influence and embolden students to riot. “Let us work as brothers and sisters. If you urge students to attack your colleague, remember others are watching, and one day, it will be you,” he advised. The Minister further shared insights into how riot investigations should be handled, warning against hastily labeling injured or present students as culprits. “When you see a student in blood after a riot, don’t immediately conclude he is a bad person. Sometimes those injured are the ones resisting destruction. If you punish the wrong people, you embolden the real perpetrators,” he explained. He urged authorities to focus on identifying ringleaders and dealing with them firmly to deter repeat offenders. “Any student found to be leading riots should be dealt with radically, but we must ensure we get the right people,” he emphasized. Mr. Atanga concluded by urging teachers, parents, assemblies, and students to work together to restore discipline, strengthen regulations, and improve infrastructure. Only through collective responsibility, he said, can the disturbing trend of school riots be curtailed. “If students obey regulations, management cooperates, and facilities are improved, we can reduce the violence. But if we continue to pamper indiscipline, we will be training troublemakers who may carry their misconduct into other schools and communities,” the Minister cautioned. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

Upper East Region Launches 94 Education Projects to Transform Schools and Bridge Infrastructure Gaps

In a sweeping initiative poised to reshape the educational landscape of northern Ghana, the Upper East Regional Coordinating Council (RCC) has unveiled a comprehensive package of 94 infrastructure projects aimed at addressing longstanding deficits in the region’s schools. The announcement, made by Regional Minister Donatus Akamugri Atanga at his inaugural press soiree in Bolgatanga, signals a new era of investment in both basic and secondary education. The ambitious programme, a collaboration between the RCC, local Members of Parliament, and the Ghana Education Trust Fund (GETFund), will touch nearly every corner of the region. Seventeen senior high schools (SHSs), two kindergartens, ten junior high schools, and thirteen primary schools are set to benefit from the intervention. Among the headline beneficiaries is Gambibgo SHS, which is in line to receive an impressive seven new projects, including a modern dining hall, additional dormitories, a science laboratory, and staff accommodations. Bolgatanga Sherigu SHS has been earmarked for 11 projects, ranging from new classroom blocks and dormitories to essential toilet facilities and an administrative block. Other institutions, such as Pusiga SHS, Kanjarga SHS, Azeem-Namoa SHS, Zamse SHS, and Navrongo SHS, will also see significant upgrades. The Bolgatanga Central Technical Institute stands out for its forthcoming six-unit technical workshop, a boost for vocational skills training in the region. “These projects are designed to ease the pressure of the double-track system, create conducive learning environments, and support the gradual phase-out of the system,” Mr. Atanga explained. Basic schools, such as Mognori JHS, Bachonsa JHS, Nyorkokor JHS, Tambalug Primary School, and Zamsa Kindergarten, are also set to see new infrastructure, ensuring that the benefits reach even the youngest learners. But the regional educational revival goes beyond bricks and mortar. The Minister emphasized ongoing reforms to improve the quality of teaching and learning. The government has restored the three-term academic calendar, strengthened Parent-Teacher Associations, and is actively reviewing the national curriculum as part of its broader “reset agenda.” Gender equity and student well-being are also at the heart of the initiative. Over 666,000 sanitary pads have already been distributed to girls in basic and second-cycle schools, a move designed to boost attendance and break down barriers to education for young women. Meanwhile, the B-STEM (Basic Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) programme has been introduced in 194 schools, and a standards-based curriculum is now fully in place across all 35 public SHSs. “These interventions reflect a holistic commitment to education,” Mr. Atanga concluded. “We are determined to create learning environments where every student can thrive, acquire relevant skills, and contribute to Ghana’s development priorities.” As construction teams prepare to break ground across the region, hope is rising that these investments will close the infrastructure gap, empower students and teachers, and lay the foundation for a brighter future in the Upper East. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

The Broken Chalkboards: Upper East CHASS Chair Warns of Rising Student Unrest, Calls for Collective Action

In a compelling segment of the documentary “The Broken Chalkboards,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of Apexnewsgh, Richard Akumbas Ayibilla, the Upper East Regional Chairman for the Conference of Heads of Assisted Secondary Schools (CHASS), lays bare the troubling rise of student unrest in the region’s schools. His address, at once candid and urgent, delves into the deepening crisis of discipline, the shifting causes of school riots, and the collective responsibility required of educators, parents, policymakers, and communities to restore order and nurture the next generation of responsible citizens. Mr. Ayibilla began by tracing the evolution of student unrest in the Upper East Region. In the past, riots were often rooted in grievances over poor food or lapses in teaching, issues, he said, that while troubling, at least had some bearing on the core mission of education. “Discipline is the keyword in every educational institution,” he emphasized. “When discipline is present, students learn, complete assignments, maintain a clean environment, and build positive relationships. Ultimately, disciplined students leave school better prepared for life.” Yet today, the triggers of unrest have shifted dramatically. “Now, most of the riots across all the schools start from mobile phones,” he lamented. In schools such as Navrongo, St. Benedict, and Bolga Tech, what might begin as a minor dispute over a stolen or misplaced phone can rapidly escalate, drawing in friends, then entire clans, and sometimes splitting along tribal lines. What should be a tool for learning instead becomes a spark for chaos. “What starts as a seemingly minor issue can draw in friends and even entire clans, turning schools into battlegrounds over technology that should only be a tool for learning.” Kindly watch the full video here: https://youtu.be/GSQR3-T6EaE. While Mr. Ayibilla acknowledges the educational potential of mobile phones, from research and AI tools to global connectivity, he is troubled by the reality he sees. Students, he observed, rarely use their devices for academic enrichment. Instead, the lure of social media, especially platforms like TikTok, drives many to create content for attention and potential income. “For some, it’s just to go into TikTok, create content, and get likes,” he observed. Particularly disheartening for him was an encounter with students who believed speaking intentionally poor English in their videos would make them go viral. These behaviors, he warned, are more than mere distractions. They can fuel deeper conflicts, leading to arguments, resentment, and property destruction. “Essential resources, from furniture to vehicles, have been damaged during riots, further straining already limited school supplies,” he said. The consequences are not limited to broken rules but extend to broken trust and broken property, deepening the crisis in already under-resourced schools. Despite these challenges, Mr. Ayibilla remains unwavering in his advocacy for core values: commitment, discipline, hard work, teamwork, honesty, and excellence. “If students are committed, discipline will naturally follow,” he asserted, drawing an analogy from the classic cartoon Captain Planet: “When you put your powers together, you are more powerful.” He proudly recounted practices from his own school, where honesty is not just taught but lived. Lost items are reliably returned, a testament to the school’s culture of integrity. “If you come to my school and lose money or valuables, don’t worry. Once a student picks it, you will get it back,” he affirmed, suggesting that habits of honesty in youth sow the seeds of integrity in adulthood. Discipline in school, he argued, is the antidote to the corruption that plagues society at large. Mr. Ayibilla is adamant that the burden of instilling discipline cannot fall solely on teachers. “Parents are very key,” he insisted. By the time students arrive at secondary school, much of their character is already formed, making the educator’s task all the more formidable. He called on parents to visit schools, build relationships with teachers, and show genuine interest in their children’s lives. “When children are in school, and parents don’t visit, they know their actions at school will go unnoticed at home,” he explained. This absence of parental oversight, he warned, fosters a double life, children well-behaved at home but unruly at school. Extending his call to the wider community, Mr. Ayibilla invoked the proverb, “he who says he doesn’t care, will at the end of the day be the one to pay the price.” Elders, residents, and even market women, he argued, have a role in supervising and guiding the youth. Discipline, in his view, is everyone’s business. Notably, Mr. Ayibilla did not shy away from critiquing the impact of government policies and political interference on school discipline. He observed that sometimes the pronouncements of politicians — such as blanket bans on corporal punishment or directives to reinstate suspended students — undermine the authority of educators and embolden indiscipline. “Punishment is not to destroy, but to correct,” he explained. Sanctions should fit the offense and serve both to reform the offender and deter others, not to crush their spirit. He called for support from all stakeholders, including chiefs, opinion leaders, and policymakers, to ensure that discipline remains consistent, fair, and focused on students’ long-term well-being. In his view, when discipline is subverted for political convenience, the whole educational ecosystem suffers. In an era where public scrutiny of schools is intense, Mr. Ayibilla called for a more nuanced, compassionate evaluation of schools and teachers. He cautioned against condemning all schools or educators for isolated incidents of misconduct, whether in food management, exam performance, or student behavior. “In every society, there are good ones and bad ones,” he noted, arguing that the actions of a few should not overshadow the dedication and integrity of the many. He also challenged the widespread politicization of exam results. The government’s primary role, he contended, is to provide resources and infrastructure, not to sit exams on behalf of students. “If children write exams and don’t pass, ministers don’t write for them,” he said. Instead, he advocated for a focus on student improvement, completion rates, and the intangible benefits of education, such as character development and social competence. Mr. Ayibilla

The Broken Chalkboards: Hon. Volmeng David Nansong suggests reintroduction of corporal punishment in schools

In recent times, become grounds for unrest rather than learning. Hon. Volmeng David Nansong, the Regional Secretary for the Parent Teachers Association (PTA), sat reflecting on an alarming trend: student riots erupting across the region’s secondary schools. His thoughts, captured in an Apexnewsgh documentary titled “The Broken Chalkboards,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen, were not only observations but a rallying call to action. For parents, educators, and policymakers alike, this was no longer a problem to ignore. David Nansong spoke with the gravity of one entrusted with the hopes of parents and the future of children. “As secretary to the PTA,” he began, “I see the immense role parents play. But what’s truly causing these issues in our secondary schools?” He leaned forward, voice steady: “There are two main issues. The first is the use of mobile phones.” Kindly watch the full video here: https://youtu.be/GSQR3-T6EaE. Mobile phones, once symbols of progress and communication, had become the root of chaos. Although regulations prohibited their use in schools, compliance was abysmally low. Many students did not, in fact, buy these devices themselves; parents, often unknowingly, supplied them. Others acquired phones through less innocent means: gifts from boyfriends, odd jobs, or even theft. School administrators, recognizing the danger, had begun confiscating these devices. The response from students was swift and organized. Plans were hatched to incite confusion and riots, creating opportunities to break into storage rooms, most notably, the senior house master’s office, where confiscated phones were kept. “I can mention Zamse Senior High Technical, Bolga Senior High, and others,” he recounted, “where students broke in and reclaimed their phones. Fortunately, the school management, with the help of the students themselves, identified and apprehended the culprits, who were handed over to the police.” But the aftermath was sobering. Offices vandalized, damages incurred, and in some instances, violence escalated, libraries burned, water systems destroyed, all in pursuit of forbidden phones. The second major catalyst was the spillover of local conflicts, particularly the recent unrest in Bawku. Rivalries between tribes, which found their way into school corridors, fanned the flames of discord. “The conflict didn’t remain in the community,” Nansong explained, “it spilled into the schools, especially in rural areas. Students affiliated with opposing tribes carried tensions into classrooms, turning academic environments into battlegrounds.” It was not uncommon, he noted, for a spark in one school to ignite unrest in another. Through informal networks and social media, students coordinated actions across institutions, threatening the fragile peace that school authorities struggled to maintain. A third, subtler factor was the introduction of the Free Senior High School policy. While the initiative was lauded for making education accessible to all, it unintentionally eroded accountability. “Students now believe that regardless of their performance, they’ll remain in school. There is no demotion, no consequence for failure,” Hon. Nansong observed. “Whether they study or not, promotion is guaranteed.” This lack of academic consequence bred apathy. The abolition of corporal punishment, though a progressive step, left teachers wary. Fearful of repercussions, teachers hesitated to enforce discipline. “Students took this as license to misbehave. Teachers, uncertain of their limits, often turned a blind eye,” Nansong lamented. The cumulative effect was a student body emboldened to challenge authority, sometimes going as far as publicly insulting national leaders on social media, and a teaching staff rendered powerless to intervene. As if these challenges were not enough, the years 2023 and 2024 brought a new crisis: food shortages in schools. Adolescents, still growing and hungry, found themselves subsisting on meager rations, plain maize, garri and beans, porridge without sugar. “At that age, they cannot sustain hunger for long,” Mr. Nansong pointed out. “The lack of proper nutrition led to frustration and, for some, the riots became an outlet for their grievances.” School leaders, bound by bureaucracy and perhaps fear of reprisal, rarely spoke openly of these shortages. Yet, for those in leadership, the link between inadequate feeding and student agitation was clear. By 2025, however, the situation seemed to improve. Reports of food scarcity dwindled, and the frequency of demonstrations reduced. The only major incident that year stemmed from renewed tribal conflict, not deprivation. Hon. Nansong’s message to parents was stern: “Charity begins at home. Parents must be vigilant about what their children bring to school, especially mobile phones.” He urged parents to interrogate the source of any phone call received from their child at school, to visit schools regularly, and to keep in touch with teachers. He recounted a tragic incident where a student, believed by his parents to be attending school, drowned at a hotel swimming pool. School records revealed the student had never reported for the term. “If parents had checked, they would have known,” Nansong said, underscoring the need for constant communication between home and school. Recent debates over student appearance, particularly the directive for students to keep their hair neat and trimmed, sparked national conversation. Mr. Nansong supported the Education Minister’s stance, comparing school regulations to those of security services and training colleges. “In the security services, there are prescribed hairstyles and uniforms. Nursing trainees can’t do their hair anyhow. Why should this be an issue for our students?” he asked. He emphasized that neatness did not preclude natural hair, but rather discouraged neglect and disorder. He dismissed comparisons to the Achimota Rastafarian case, noting that religious exceptions were different from general discipline. “This is not about curtailing freedom; it’s about instilling the standards needed for communal learning and personal responsibility.” Hon. Nansong’s reflections were not a condemnation of today’s youth. “Not all students are bad,” he affirmed, “but certain behaviors threaten the peace and progress of all.” He recounted with sadness how, at Zamsi Senior High, students vandalized the senior housemaster’s office and stole confiscated mobile phones before their final exams. The responsible students were held accountable for the damages. “If a poor widow sends her child to school, and the child destroys property, it is only fair that the student pays for it,” he reasoned. “If you know

Tensions Rise on Campus: UTAG-UG Demands Resignation of GTEC Leadership Over “Persistent Overreach”

A wave of discontent swept across the University of Ghana campus on January 19, 2026, as the University Teachers’ Association of Ghana, University of Ghana Branch (UTAG-UG), took a bold public stand. In a strongly worded statement, the Association called for the immediate resignation of the Director-General of the Ghana Tertiary Education Commission (GTEC), Professor Ahmed Jinapor Abdulai, and his Deputy, Professor Augustine Ocloo, accusing the Commission’s top leadership of overstepping its bounds and neglecting its true mandate. The statement, signed by Dr. Jerry Joe Harrison and Dr. Godfred B. Hagan, UTAG-UG’s President and Secretary, respectively, was more than a critique; it was a clarion call for change at the highest levels of Ghana’s tertiary education system. According to UTAG-UG, the GTEC’s leadership had consistently engaged in actions that undermined the very institutions they were tasked to support, flouting the provisions of the Education Regulatory Bodies Act, 2020 (Act 1023). UTAG-UG argued that while GTEC was established to ensure quality, equitable access, transparent governance, and accountability in tertiary education, the Commission had strayed from these responsibilities. Instead, the Association charged, GTEC had become entangled in peripheral issues, leaving deep systemic problems, such as inadequate funding, deteriorating infrastructure, poor staff remuneration, and increasing workloads for lecturers, largely unaddressed. The Association’s grievances did not stop at neglect. The statement accused GTEC of actively undermining institutional autonomy, citing instances where the Commission had reversed decisions made by legally constituted Governing Councils without proper legal authority. UTAG-UG further questioned GTEC’s role in the controversial removal of the former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cape Coast, Professor Johnson Nyarko Boampong, demanding transparency and legal justification for such interventions. A particularly contentious episode highlighted in the statement was GTEC’s October 1, 2025, directive, which ordered lecturers to retire immediately upon reaching age 60, instead of allowing them to complete the academic year as per the established rollover system. UTAG-UG described this move as disruptive and unconstitutional, warning that it jeopardized academic planning and continuity. The Association also objected to GTEC’s subsequent request for submissions on post-retirement contracts, emphasizing that such agreements are matters of national negotiation and Cabinet approval, not unilateral administrative decision. Beyond these policy clashes, UTAG-UG criticized what it described as an adversarial and “incompetent” style of leadership at GTEC, claiming it had eroded staff morale across Ghana’s public universities. The Association cited a recent incident at the University of Ghana, where GTEC threatened sanctions over an alleged increase in student levies—an action ultimately based on what proved to be a false media report. For UTAG-UG, the pattern was clear: GTEC’s persistent interference was not only hampering academic freedom and institutional autonomy, but also threatening the very future of Ghana’s tertiary education. The Association’s warning was stark; unless Professors Jinapor Abdulai and Ocloo resigned by January 31, 2026, UTAG-UG would escalate its demands to the Chief of Staff and consider industrial action. The Association also used its statement to push for systemic reform, calling for the immediate passage of a Legislative Instrument to guide the proper application of Act 1023, and to prevent what it termed “future abuse of power” by the Commission’s leadership. As the statement circulated, UTAG-UG’s leaders urged their colleagues across other campuses and all stakeholders in tertiary education to join their call for accountability. Their message was clear: it was time to “restore sanity and hope” to Ghana’s public universities, and to ensure that the governance of higher education truly serves the interests of students, faculty, and the nation at large. With tension mounting and a deadline looming, the spotlight remained firmly fixed on GTEC’s leadership and on the future direction of higher education governance in Ghana. Source: Apexnewsgh.com