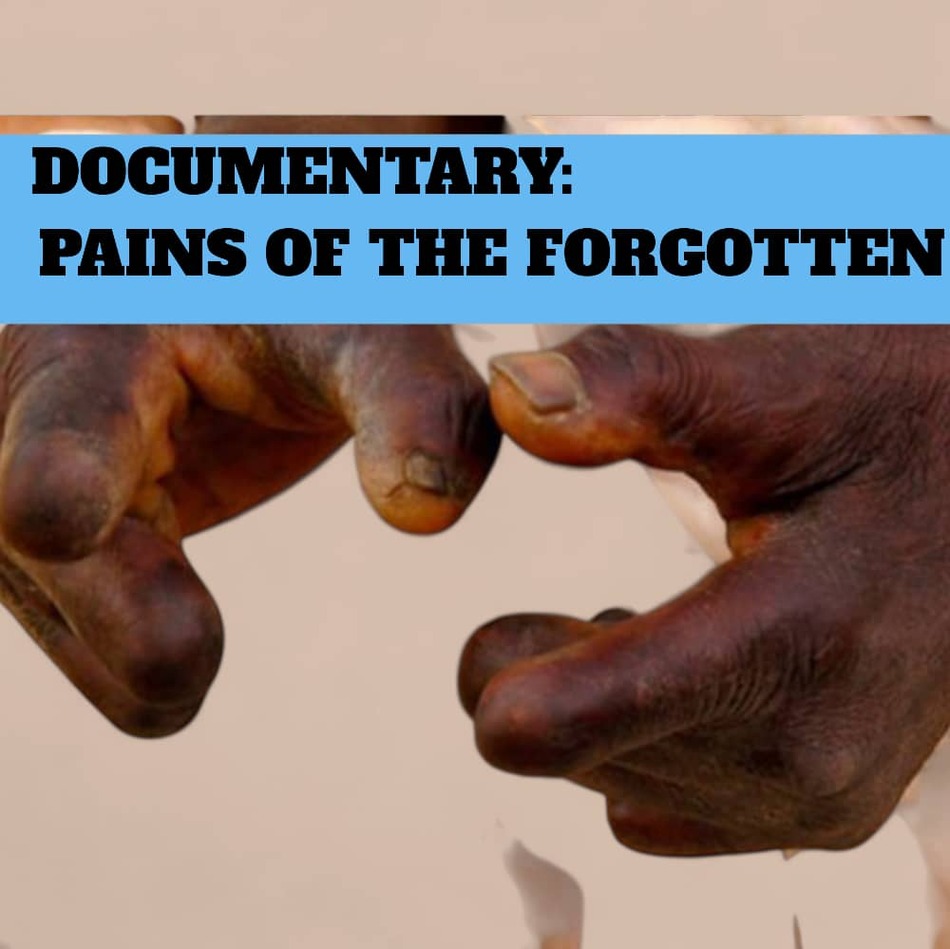

Once upon a time, in the lively community of Bongo Soe, Mr. Adombire Ayuumbeo was the embodiment of diligence and pride. The sun’s first rays often found him by the dam near his house, tending to rows of tomatoes and vegetables. His farm was a patchwork of green, a source of sustenance for his family and a modest income from the surplus sold in the market. But farming was only a part of his industrious life; Mr. Ayuumbeo also spent hours cutting firewood and harvesting roofing grass, always ensuring his household’s needs were met. His hands, once strong and skilled, provided security, comfort, and hope to those who depended on him. This story, however, took a drastic turn. Leprosy crept silently into Mr. Ayuumbeo’s life, robbing him of the very tools of his trade, his fingers. The disease did not merely bring pain and disfigurement; it stripped him of his ability to work, leaving him “idle and helpless.” Once a man who never sat still, he now found himself confined to his home, watching the world move on without him. “When I remember the way I used to work and support my family, tears start pouring from my eyes,” Mr. Ayuumbeo confided in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. “Now I can’t farm, I can’t cut firewood, I can’t do anything. Sometimes I think I should die than to live.” For Mr. Ayuumbeo, the greatest agony is not only physical, but also the heavy shroud of stigma that leprosy brings. Once greeted with respect, he now feels abandoned and judged by the very people he once called neighbors and friends. “You don’t have anything, and your body too makes it hard to mingle with people. People stigmatize you. I don’t know why God gave me a disease that people don’t respect.” The sense of isolation is profound. The silence from others echoes louder than his disability, and the weight of judgment is heavier than any load he once carried from the fields. Despite these trials, Mr. Ayuumbeo tries to hold onto gratitude. “I thank God that the sores have healed and I can walk without difficulty. But I cannot do what I used to do.” His gratitude is laced with sorrow—a longing for lost strength, lost routine, and lost purpose. Each day, he wakes to face both the physical limitations of his body and the invisible barriers erected by society’s misunderstanding. His thoughts often return to his family. With a wife and children looking to him for support, the burden of helplessness is magnified. He worries about their future, how to keep them fed, clothed, and safe. “When I was active, I used to pay taxes. Now I cannot work, but I still belong to the government. I vote. I have my voter ID. The government of Ghana owes me and my family. If there’s any way they can help us sustain our lives, they should do it.” His appeal is not just for himself, but for every leprosy survivor who has been left behind, still a citizen, still deserving of dignity and support. Mr. Adombire’s story is woven into the larger tapestry of Bongo’s leprosy survivors—a tapestry colored by pain, but also by resilience and hope. Organizations like the Development Research and Advocacy Center (DRAC) are working to ensure that people like Mr. Ayuumbeo are not forgotten. DRAC’s efforts go beyond charity; they are about rebuilding lives. With the drilling of ten boreholes, clean water is now within reach for many who once struggled. Water health committees educate communities about hygiene, crucial in the fight against neglected tropical diseases. But perhaps most remarkable is DRAC’s commitment to economic empowerment. Training sessions in basket weaving and soap-making provide patients and caregivers with skills, materials, and, most importantly, a renewed sense of purpose. “Buyers come to the community to purchase baskets, and we provide materials and training,” says Jonathan Adabre, DRAC’s Executive Director. These initiatives are more than income; they are threads of dignity, restoring connections to the community and to self-worth. Across Bongo, the story of leprosy is changing. It is no longer solely a tale of suffering, but one of resilience written in the determined footsteps of a nurse on his rounds, in the laughter of women weaving baskets, and in the hope that arrives with every borehole drilled. Yet, Mr. Ayuumbeo’s plea still rings out, a call for compassion, inclusion, and meaningful action. His journey, and that of so many others, is a reminder that the scars of leprosy go beyond the physical. It is up to all, the community, government, and organizations, to ensure these lives are lifted from the silence of stigma into the light of dignity and support. Only then will the story of Bongo’s leprosy survivors be one not just of what was lost, but of what can still be regained. WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY VIDEO Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

The Unseen Battles of Leprosy Survivors in Bongo

For ten long years, Matilda Nyaaba endured a mysterious torment. In her quiet village of Bongo Balungu, life was punctuated by fainting spells, nosebleeds, and unexplainable pain. Apexnewsgh reports Each episode left her weaker, and each visit to yet another health facility only compounded her confusion. What was this invisible enemy that drained her strength and hope, year after year? No one seemed to have an answer. Matilda’s ordeal was brought to light in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. Her story, like those of many leprosy sufferers, was one of searching in the dark. Even as her family stood by her, her neighbors whispered, eyed her with suspicion, and kept their distance. Some said she was cursed; others assumed she had HIV. To protect herself from the sting of their words, Matilda began to retreat indoors, leaving her home only for the most essential of chores. The isolation bit deeper than the disease itself, eroding her spirit and sense of belonging. It was only after a particularly harrowing episode, a collapse so severe she was rushed to the hospital, that a turning point arrived. There, a disease control officer finally recognized the signs of leprosy and placed Matilda on a monthly treatment regimen. For the first time, hope flickered in her life. The medicine brought relief, but not certainty. Supplies at the hospital ran out from time to time, and Matilda would wait anxiously for a call or a visit, never knowing when the next dose would arrive. Still, she persevered. Her wish was simple: that no one else should have to wander in confusion or suffer in silence as she had. Matilda’s journey reveals a truth often overlooked: the wounds of leprosy are as much emotional and social as they are physical. The pain of exclusion, the silence of misunderstood suffering, and the longing for dignity weigh heavily on those afflicted. Her resilience is a quiet call for compassion, understanding, and real action, so that no one else in her community will have to endure the same lonely road. Aniah’s Journey Through Leprosy’s Trials In the village of Bongo Soe, another story of quiet resilience unfolds. Aniah Lamisi was once a farmer whose days were filled with the rhythm of the land. She took pride in the sweep of her hoe, the bounty of her harvest, and the strength of her hands. Farming gave her purpose, connection, and identity. But leprosy crept into her life without warning, first as a tingling in her fingers, then as a relentless force that twisted and weakened her hands. Tasks that once came easily, cooking, fetching water, and gathering firewood, became daily struggles. The simple act of lifting a water container to her head was now a painful ordeal. Cooking over a fire brought blisters instead of warmth. With her hands disfigured, her independence slipped away, and Aniah found herself an observer in her own life, unable to work or contribute as she once did. The loss went deeper than the physical. Though her neighbors did not reject her outright, the shame of asking for help, of reaching out with altered hands for food, wounded her pride. She withdrew from communal life, carrying her pain in silence. Like Matilda, Aniah’s only hope was regular medication—but the health center’s supplies were unreliable. Some months, she received her treatment; other times, she waited in vain, watching her health and hope falter. Each missed dose was a reminder of how fragile her world had become. Yet Aniah’s spirit refused to break. In rare quiet moments, she counted her blessings: a body that still allowed her to dress herself, fleeting moments of calm, and the knowledge that others faced even greater struggles. She dreamed of something more, a chance to learn a trade, to regain purpose, to earn her own living. Vocational training, she thought, could be a bridge back to dignity and self-respect. While Matilda and Aniah’s stories are deeply personal, they are not unique. Across Bongo and its surrounding communities, many battle the same invisible foe, facing not just disease but the crushing weight of stigma, poverty, and uncertainty. But hope comes not only from within. Organizations like the Development Research and Advocacy Center (DRAC) are changing the landscape for leprosy patients. With ten boreholes drilled in affected areas, access to clean water is no longer a dream. Water health committees teach hygiene, helping prevent further spread of neglected tropical diseases. Most transformative are DRAC’s economic empowerment programs, training in basket weaving and soap-making, providing materials, and connecting patients with buyers. For women like Aniah and Matilda, these opportunities are more than a source of income; they are a path back to belonging and pride. The story of Bongo’s leprosy survivors is one of resilience, not just suffering. It is written in Matilda’s quiet hope, in Aniah’s determination, in every basket woven and every borehole drilled. It is a story that demands not pity, but recognition and commitment. For these women and countless others, the journey continues toward healing, dignity, and a future where no one must walk alone in the shadows. WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY VIDEO; Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

A Journey of Compassion: The Unsung Heroes Battling Leprosy in Bongo

A battle is being fought, a struggle not only against disease, but against stigma, neglect, and despair. At the center of this fight is staff nurse David Asamani of the Bongo Soe Health Center, whose daily acts of compassion have transformed the lives of leprosy patients who have been forgotten by society. Apexnewsgh reports David Asamani is not just a nurse. To those he cares for, he is a lifeline, a confidant, and sometimes even family. While many health workers draw the boundaries of their duties at the clinic doors, Asamani’s responsibilities stretch far beyond. For him, the well-being of his patients does not end with the administration of medicine; it is a holistic mission that takes him across dusty roads and into the humble homes of those suffering from leprosy. The story of his devotion was brought to light during the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. Asamani’s words echo the silent struggles of the people he serves: “Anytime I go to give them the medicine, I can see the suffering they are suffering,” he shares. The pain he describes is not just physical—but a deep emotional and social wound inflicted by poverty, isolation, and stigma. Many of Asamani’s patients live in the shadows, their disabilities making even the most basic tasks, cooking, cleaning, and earning a living, almost insurmountable. “Some of them will tell you they don’t even have food to eat while taking the medicine. Most of them don’t have anyone to help with household chores or economic activities; they just struggle on their own despite their disabilities.” One day, a new challenge arose. The district office called on leprosy patients to renew their health insurance and register for the government’s LEAP program. For most, this would mean a simple trip to town. But for these patients, left unsupported by family and shunned by their communities, it was an impossible journey. Asamani refused to let circumstances defeat them. “I had to use my motorbike to carry three of them to the district,” he recalls. The image is striking, a single nurse balancing duty and compassion, ferrying his patients toward a lifeline they could not reach alone. But compassion alone cannot fill empty medicine cupboards. Asamani’s dedication is tested time and again by the persistent shortages of vital drugs for leprosy and other neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). “Sometimes when patients need the medicine most, it is not available. By the time it comes, the harm has already been caused,” he laments. His plea is simple but urgent: “We will be grateful if the medicines could be available at all times. That will be very helpful.” Despite the government providing treatment for free, the reality on the ground is a different story. Attention is often focused elsewhere, and NTD patients find themselves at the bottom of the list. “Our concentration is on other diseases, neglecting these people. Meanwhile, these diseases cause a lot of economic challenges in our society. If we don’t take good care of them today, tomorrow you don’t know who might be affected,” Asamani warns, his voice carrying both frustration and hope. To Asamani, the fight against leprosy is not just medical, it is humanitarian. Each home visit, each ride on his motorbike, each moment spent listening to a patient’s worries, is a step toward restoring dignity and hope. His story is a powerful reminder that treating disease means more than dispensing drugs—it means confronting the poverty, stigma, and neglect that allow such illnesses to flourish. Yet, Asamani is not alone. The fight against leprosy in Bongo is bolstered by the work of the Development Research and Advocacy Center (DRAC), led by Executive Director Jonathan Adabre. DRAC’s approach is as holistic as Asamani’s devotion. With support from Anesved Fundación, DRAC raises awareness about the early signs of leprosy, elephantiasis, and yaws. “Many believe leprosy is genetic, but it takes up to 20 years to manifest. That misconception must end,” says Adabre. Their campaigns battle not only illness, but ignorance. DRAC’s impact is tangible. The organization has drilled ten boreholes across affected communities, ensuring access to clean and safe water. They have set up water health committees that teach hygiene practices, crucial in the fight against NTDs. But perhaps most transformative is their focus on economic empowerment. DRAC organizes training sessions in basket weaving and soap-making, providing materials and connecting patients and caregivers to markets. “Buyers come to the community to purchase baskets, and we provide materials and training,” Adabre notes. For many, these initiatives offer more than an income; they restore a sense of worth, dignity, and belonging. The story of Bongo’s leprosy patients is one of resilience, not just suffering. It is written in the determined footsteps of a nurse on his rounds, the laughter of women weaving baskets, and the hope that comes with every borehole drilled. It is a story that calls for more than sympathy; it demands action, understanding, and a commitment to never again let these lives be forgotten. WATCH THE VIDEO DOCUMENTARY: Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

Stigmatization in Bongo is very high—District NTDs Focal Person

In the heart of Ghana’s Upper East Region, the Bongo District is fighting a quiet but devastating battle. Over the last six years, this rural district has recorded a deeply worrying rise in leprosy cases, with 57 new cases reported from 2019 to September 2025. For many, the word “leprosy” conjures up images from distant history books, but in Bongo, it is a daily reality, one made worse by stigma and isolation. This troubling revelation came from Mr. Kpankpari Wononuo Bismark, the District Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) Focal Person, in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. In a candid conversation, Mr. Bismark described the situation as “alarming,” drawing attention to the many layers of hardship leprosy patients endure beyond their diagnosis. “Stigmatization in Bongo is very high,” Mr. Bismark lamented. “Some patients are isolated, left in separate rooms, made to live alone. This worsens their mental health.” For many, the fear of being shunned by neighbors and loved ones is just as crippling as the disease itself. Some wait until their symptoms are too severe to hide, seeking help only when sores and deformities make life unbearable. “When we identify leprosy early, we can treat it within nine months,” Mr. Bismark explained. “But when patients report late with sores and deformities, the damage remains for life.” The consequences of this fear-driven delay are profound. Advanced leprosy often leaves patients with lifelong disabilities, making it impossible for them to farm or work. In a region where most people depend on their hands to earn a living, the economic toll can be just as devastating as the physical suffering. “Most of them cannot do meaningful work because of deformities,” Mr. Bismark said. “That is why interventions from NGOs that provide small capital for farming, weaving, or soap-making are so helpful. These initiatives help reduce idleness and restore dignity.” But the challenges don’t end with stigma and economics. Mr. Bismark also pointed to the struggles of accessing medicine, which must be requested from the regional health directorate and sometimes runs out. Still, he remains optimistic about the impact of treatment: “The good thing is that when we start the medicine, transmission to others is minimized, even though sometimes we run out of drugs briefly.” The changing climate also brings fresh hardships for leprosy patients. During the harsh dry season, cracked skin can lead to open sores that quickly become infected. Without easy access to clean water and proper hygiene, these sores can become septic, threatening not just health but life itself. “NTDs are neglected diseases, and sadly, the people suffering from them are also neglected,” Mr. Bismark noted. “Many patients live far from clean water sources, making hygiene very difficult.” Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) remain critical challenges. In remote villages, fetching water involves long, painful journeys, a heavy burden for those already weakened by disease. This lack of WASH infrastructure leaves patients especially vulnerable to complications and further social exclusion. Despite these daunting obstacles, hope persists in the form of early detection and community support. “Leprosy is airborne, and elephantiasis is caused by mosquito bites. Everyone is at risk. That is why we keep telling the community: support patients, don’t stigmatize them, because you never know when you could also be affected,” Mr. Bismark urged. The fight against leprosy in Bongo is not waged by government alone. Non-governmental organizations like the Development Research and Advocacy Center (DRAC), led by Executive Director Jonathan Adabre, are helping to fill the gap. DRAC’s holistic approach tackles both the practical and social sides of the disease. “With support from Anesved Fundación, we raise awareness about early signs of diseases like leprosy, elephantiasis, and yaws,” Adabre explained. “Many believe leprosy is genetic, but it takes up to 20 years to manifest. That misconception must end.” DRAC’s projects are as varied as they are vital. The organization has drilled ten boreholes across affected communities, ensuring that more families have access to clean, safe water. They have also formed water health committees to educate locals on hygiene practices, crucial for managing NTDs. But perhaps their most transformative work lies in supporting economic empowerment. DRAC provides training and materials for basket weaving and soap-making, linking patients and caregivers to markets. “Buyers come to the community to purchase baskets, and we provide materials and training,” Adabre says. These initiatives offer more than income; they restore a sense of purpose and connection. The story of leprosy in Bongo is one of pain, but also of resilience and hope. It is a reminder that diseases like leprosy do not just attack the body, they disrupt families, livelihoods, and entire communities. Breaking the cycle requires more than medicine. It calls for compassion, early detection, and the kind of holistic support that brings patients out of the shadows and back into the embrace of their community. As Bongo continues its fight, the district’s journey stands as a testament to the power of partnership, awareness, and above all, human dignity. WATCH THE VIDEO DOCUMENTARY BELOW: Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience in Ghana–VIDEO ATTACHED

A documentary by Ngambebulam Chidozie-Stephen (ApexNewsGH) Editor in Chief Leprosy is one of humanity’s oldest diseases, yet in 2024, it remains a pressing global health crisis. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 188 countries and territories reported a total of 172,717 new cases last year. The impact is not evenly distributed; women and girls comprised over 40% of new patients, and children accounted for more than 9,000 cases. Most troubling, over 9,100 new sufferers were diagnosed with the most severe form, grade 2 disability, a diagnosis that can mean permanent deformity and a lifetime of hardship. While leprosy’s global shadow is long, its most profound pain is felt in places like Ghana’s Upper East Region. Here, in the Bongo district, a community of just over 120,000 people, leprosy remains a silent threat. From 2019 to September 2025, 57 cases were officially reported, and the true number may be higher due to fear, stigma, and misunderstanding. Leprosy is just one of many Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) that persist in Ghana. These diseases, fourteen of which are endemic in the country, disproportionately affect the poorest, deepening cycles of poverty and exclusion. Pain Behind Closed Doors: Matilda’s Story In the tight-knit community of Bongo Balungu, Matilda Nyaaba’s life is defined not only by the disease itself but by the isolation it breeds. For ten years, Matilda endured unexplained symptoms, fainting spells, nosebleeds, and growing weakness, a mystery to both her and the health professionals she visited. “Each episode left me weaker,” Matilda shares, remembering the confusion and fear that accompanied each new symptom. The only constant in her life became her monthly trips for medicine. Her family, she explains, has been a source of support, but the wider community’s reaction has been another story. She describes a self-imposed solitude, “I advised myself to stay indoors. They would use my condition against me.” Even basic errands, like fetching water from the borehole, are shadowed by the fear of being shunned. Whispers followed her: “Some described my illness as HIV, others as a curse. This has deeply affected my mental health; I don’t know what I’m thinking anymore.” Yet, Matilda’s resilience endures. She dreams of more than just survival: “If the government could help, maybe by providing vocational training, I could regain my dignity and hope for a brighter future.” From Provider to Dependent: Ania’s Struggle Before leprosy, Aniah Lamisi was at the center of her family’s livelihood in Bongo Soe. Farming was her pride and her purpose. But illness arrived quietly, a tingling in her fingers, followed by the slow, cruel twist of her hands. Aniah’s life shrank as the disease progressed. She could no longer wield a hoe or prepare meals over an open fire without pain. Even fetching water, a lifeline in the village, became a daily ordeal. She reflects on her new reality: “Some people have lost everything, even their mental faculties. I can still care for myself, dress well, and sometimes mingle with groups. That’s how I console myself. But if I can’t farm, how do I feed myself? I just sit and eat, if there’s food. Who will work for me?” Her appeal is simple but urgent. “If the government can provide us with a vocation or manual labor, we could earn a living. Now, I just wait and hope for food. Even cooking is painful, but who else will do it for me?” In Bongo Swing, Mr. Adombire Ayuumbeo once embodied industry and self-reliance. He farmed, cut firewood, and harvested thatch, supporting his family with pride. But when leprosy struck, it took his independence, disfigured his body, and left him idle. He describes the loss with raw honesty: “Everything I used to do to earn a living is gone. Now I am helpless. I sit alone. Nobody helps me. Sometimes I think it would be better to die than live like this. People stigmatize you. I don’t know why God gave me this disease that people don’t respect. When I remembered all these things happening to me, my tears began to fall.” He issues a plea not just for himself, but for others like him: “If the government can help sustain our lives, they should do it. I vote, I have a voting ID. If the government has anything to help, we would appreciate it.” The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being, address neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) like leprosy under Target 3.3. This target states: “By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and neglected tropical diseases, and combat hepatitis, waterborne diseases, and other communicable diseases.” This means that the global community, through the United Nations and its member states, has committed to eliminating NTDs, including leprosy, as public health problems by 2030. The aim is to reduce illness, disability, stigma, and death caused by these diseases through prevention, early detection, treatment, and improved access to health services, especially for vulnerable populations. In essence, the SDGs recognize that fighting NTDs is essential for achieving universal health coverage, reducing inequalities, and promoting the well-being of all people, particularly those living in poverty and marginalized communities. Ending NTDs like leprosy not only improves health outcomes but also supports broader development goals such as education, gender equality, and economic productivity. The rising trend of leprosy in Bongo is confirmed by Mr. Bismark Kpankpari Wononuo, the district’s Disease Control Officer, who doubles as the NTDs coordinator. He explained that the numbers increase every year. He credits increased detection to community volunteers but warns that the real challenge is stigma. According to him, “Many don’t come early for treatment due to discrimination. Early detection is key; if we treat early, within nine months, it can be cured. But when affected persons decide to report late, it causes deformities to remain for life.” He further sends a clear message to the community by letting them know that Leprosy is treatable and that early detection is crucial. “Everybody is at risk.” However, he acknowledged that there are

Health Minister Warns Ghana Could Face 180,000 Unemployed Health Professionals by 2028

Health Minister Kwabena Mintah Akandoh has sounded the alarm over a looming crisis in Ghana’s health sector, warning that the country could see as many as 180,000 trained but unemployed health professionals by the end of 2028 if urgent action is not taken. Currently, the number of unemployed health workers stands at approximately 74,000. However, with thousands more graduating each year, the figure is projected to more than double in the next three years. “By the end of 2026, we have an additional 23,000. By the end of 2027, we have an additional 35,000. By the end of 2028, we have about 47,000. So by the end of 2028, if we don’t employ anybody, this 74,000 is still outstanding, we will have not less than 180,000 trained and they will be at home,” the Minister explained. Mr. Akandoh made these remarks during an interview on The Point of View on Channel One TV, where he addressed the ongoing employment challenges in the health sector. He noted that the government is implementing a gradual recruitment plan and exploring international opportunities as part of efforts to manage the growing backlog. “So there is a strategy going forward. What we are seeking to do now is that gradually, government will be employing some of them as we move along,” he said. To further address the situation, Mr. Akandoh revealed that Ghana is considering “managed migration” by partnering with countries interested in hiring Ghanaian health professionals. “About 13 countries have responded, but the difficulty is that most of these countries that have responded, they need a specialist,” he added. The Minister also disclosed that Ghana would require at least GHS6 billion annually to clear the backlog of unemployed health professionals. His comments come amid mounting pressure from unemployed nurses and midwives demanding job placements, as well as criticism from the Minority in Parliament regarding the government’s handling of health sector employment. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

President Mahama Extends Dialysis Subsidy to Private Health Facilities: Minister Announces at Medical Trust Fund Inauguration

Minister of Health, Kwabena Mintah Akandoh, has revealed that President John Dramani Mahama has directed the extension of the government’s dialysis subsidy to include private health facilities. The announcement was made during the inauguration of a 13-member governing board for the Ghana Medical Trust Fund, popularly known as “Mahama Cares,” a flagship initiative aimed at providing financial support for the treatment of chronic non-communicable diseases. According to Mr. Akandoh, the government will now cover GH₵500 of the cost charged per dialysis session at private health facilities, mirroring the subsidy already available at public hospitals. “The current arrangement for payment of dialysis is that if you go to public health facilities, we have a maximum amount of money we pay per session, that’s around 499, something about 500 Ghana cedis. What we have realised is that there are people who also go to private facilities, and so, it’s a necessity; the President has directed us to give what is paid to the public facilities,” he explained. He further clarified, “So, for example, if you go to private facility A and they are charging you 1,000 Ghana cedis, the government will pay the 500 Ghana cedis, and you top up, to be fair to everybody. So, the CEO for the National Health Insurance has been directed accordingly to take up that challenge.” The Minister also used the occasion to appeal to corporate organisations and individuals to support the government’s efforts by contributing to the Medical Trust Fund. “We cannot do it all alone. It is the partnership between the government and corporate Ghana that will take us far. Other corporate bodies have come on board, like Telecel Group of Companies, and there are some banks as well,” Mr. Akandoh noted. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

BasicNeeds-Ghana and Mental Health Alliance Urge Government to Prioritize Mental Health Support During Disasters

As the world observed World Mental Health Day on October 10, 2025, BasicNeeds-Ghana and the Alliance for Mental Health and Development (Mental Health Alliance) made a passionate call for Ghana to prioritize Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Services (MHPSS) during catastrophes and emergencies. This year’s global theme, “Access to Services: Mental Health in Catastrophes and Emergencies,” highlights a growing global concern: the urgent need to support the psychological and emotional well-being of people affected by crises. In a press statement, the Mental Health Alliance noted that Ghana has not been spared from disasters, from perennial floods, droughts, and fires to building collapses, road accidents, and conflicts. These incidents, the Alliance said, have left “individuals, families, and communities with lasting traumatic, psychological, and emotional injuries and scars.” Despite efforts to provide food, shelter, and water during emergencies, mental health support is often neglected. “While much attention and effort are given to physical survival, the psychological toll of such crises, though profound and often invisible, is mostly neglected,” the statement emphasized. The Alliance expressed deep concern about how vulnerable groups, including women, children, persons with disabilities, and people already living with mental health conditions, are disproportionately affected. “Without MHPSS, recovery remains incomplete,” it stated. “Families struggle to rebuild livelihoods, children’s education is disrupted, and communities remain fragile.” Calling for urgent action, the Alliance appealed to the Government of Ghana to: Integrate MHPSS into disaster preparedness and response frameworks such as NADMO and the MMDAs. Include MHPSS experts among first responders in emergencies. Increase investment in mental health within Ghana’s health budget. Equip frontline health workers and humanitarian actors with skills in psychosocial first aid. Strengthen community-based mental health support systems. Combat stigma through community-level awareness campaigns. “Addressing the mental health and psychosocial needs of survivors is not optional — it is essential for individual healing, family stability, and community resilience,” the statement added. The Alliance also commended Ghana’s progress, particularly the passage of the Mental Health Act, 2012 (Act 846) and the integration of mental health into primary health care. However, it warned that limited resources, urban-centered services, and lingering stigma continue to hinder access — especially in times of crisis. “As we observe World Mental Health Day 2025, let us reaffirm our commitment to make provision of mental health and psychosocial support part and parcel of our health and wellbeing needs,” the statement concluded. “No one should be left behind in times of crisis.” Source: Apexnewsgh.com

Nursing and Midwifery Council Warns Against Unprofessional Conduct on Social Media

The Nursing and Midwifery Council of Ghana (N&MC) has issued a stern warning to all students and practitioners in the field, urging them to refrain from any form of unprofessional conduct, especially on social media platforms. In an official statement, the Council emphasized that it will not hesitate to invoke disciplinary measures, including suspension or revocation of licenses, against anyone found guilty of breaching the professional Code of Conduct. This decisive stance follows a series of widely circulated publications and videos featuring trainees, nurses’ assistants, nurses, and midwives that have been trending on various social media platforms. According to the Council, such content is grossly unprofessional and stands in direct violation of the Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct governing the nursing and midwifery professions in Ghana. The statement highlighted several concerns, including the misuse of the nursing and midwifery uniform to create unauthorized social media content, the use of abusive or offensive language directed at leadership and other stakeholders, and the sharing of misleading or unverified health information under the guise of professional advice. The Council has encouraged stakeholders to report any such misconduct for prompt and appropriate action, stressing that any behavior undermining professional values tarnishes the image of the profession and erodes public trust in the healthcare system. Reiterating its exclusive mandate, the Nursing and Midwifery Council reminded the public that only it has the authority to accredit institutions and license individuals to practice as nurse assistants, nurses, and midwives in Ghana. Source: Apexnewsgh.com

Ghana Reaffirms Strong Commitment to Refugee Protection at UNHCR Executive Committee Session

Ghana has once again underscored its steadfast dedication to refugee protection and durable solutions on the global stage, making its position clear during the 76th Annual Plenary Session of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Executive Committee in Geneva. Leading the Ghanaian delegation, Minister for Interior Mohammed Muntaka Mubarak highlighted the country’s enduring commitment to the ideals of the Global Compact for Refugees (GCR). He emphasized that Ghana remains resolute in pursuing sustainable interventions that benefit both refugees and their host communities. During his plenary address, the Minister outlined Ghana’s progress in working collaboratively with countries of origin to ensure the effective implementation of durable solutions, including addressing their legal aspects. He also spotlighted the Ghana Refugee Agribusiness Sustainability Programme (GRASP), a flagship initiative in partnership with UNHCR that creates sustainable livelihoods for refugees and local residents alike. Ghana’s ongoing efforts extend beyond national borders, with strengthened cooperation among neighboring countries to develop a sub-regional strategy. This approach focuses on bolstering national security, safeguarding refugee rights, and enabling lasting, cross-border solutions. In his concluding remarks, Minister Mubarak expressed Ghana’s appreciation to outgoing UNHCR High Commissioner Filippo Grandi, commending his exceptional leadership and commitment to upholding the rights and dignity of refugees worldwide. Ghana’s renewed pledge at the UNHCR Executive Committee session reaffirms the nation’s long-standing legacy of hospitality, humanitarianism, and leadership in advancing peace and stability across the sub-region. Source: Apexnewsgh.com