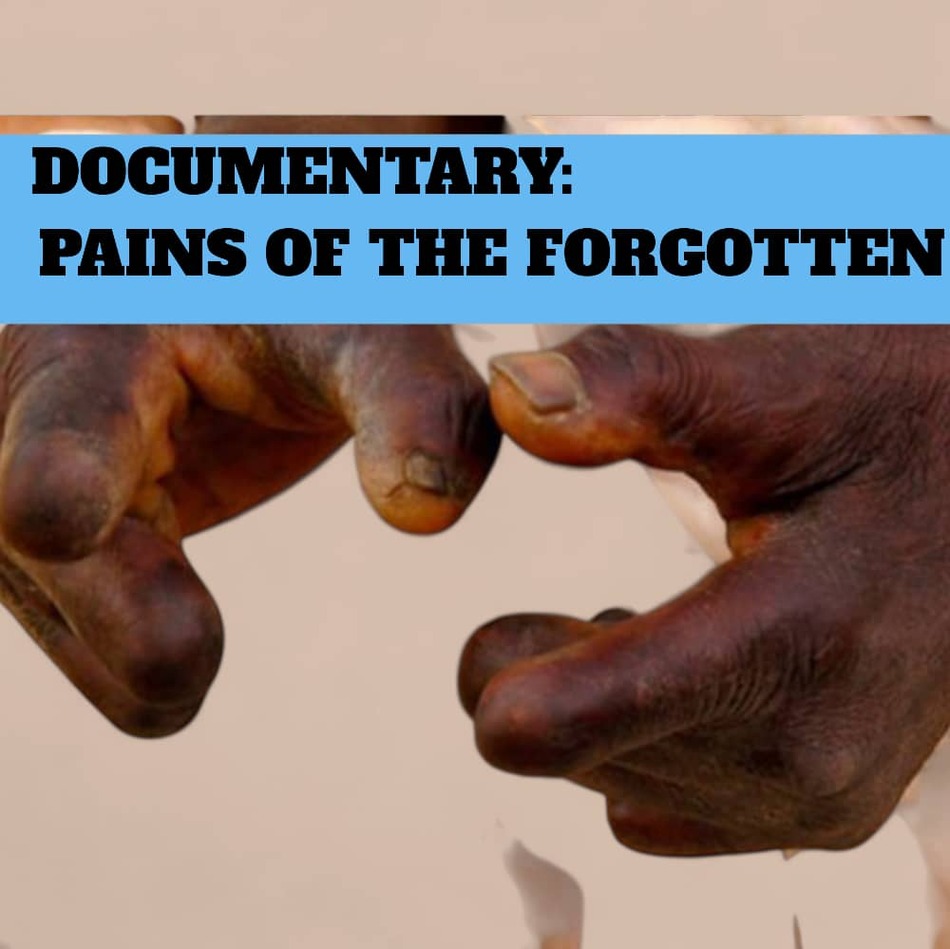

Once upon a time, in the lively community of Bongo Soe, Mr. Adombire Ayuumbeo was the embodiment of diligence and pride. The sun’s first rays often found him by the dam near his house, tending to rows of tomatoes and vegetables. His farm was a patchwork of green, a source of sustenance for his family and a modest income from the surplus sold in the market. But farming was only a part of his industrious life; Mr. Ayuumbeo also spent hours cutting firewood and harvesting roofing grass, always ensuring his household’s needs were met. His hands, once strong and skilled, provided security, comfort, and hope to those who depended on him. This story, however, took a drastic turn. Leprosy crept silently into Mr. Ayuumbeo’s life, robbing him of the very tools of his trade, his fingers. The disease did not merely bring pain and disfigurement; it stripped him of his ability to work, leaving him “idle and helpless.” Once a man who never sat still, he now found himself confined to his home, watching the world move on without him. “When I remember the way I used to work and support my family, tears start pouring from my eyes,” Mr. Ayuumbeo confided in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. “Now I can’t farm, I can’t cut firewood, I can’t do anything. Sometimes I think I should die than to live.” For Mr. Ayuumbeo, the greatest agony is not only physical, but also the heavy shroud of stigma that leprosy brings. Once greeted with respect, he now feels abandoned and judged by the very people he once called neighbors and friends. “You don’t have anything, and your body too makes it hard to mingle with people. People stigmatize you. I don’t know why God gave me a disease that people don’t respect.” The sense of isolation is profound. The silence from others echoes louder than his disability, and the weight of judgment is heavier than any load he once carried from the fields. Despite these trials, Mr. Ayuumbeo tries to hold onto gratitude. “I thank God that the sores have healed and I can walk without difficulty. But I cannot do what I used to do.” His gratitude is laced with sorrow—a longing for lost strength, lost routine, and lost purpose. Each day, he wakes to face both the physical limitations of his body and the invisible barriers erected by society’s misunderstanding. His thoughts often return to his family. With a wife and children looking to him for support, the burden of helplessness is magnified. He worries about their future, how to keep them fed, clothed, and safe. “When I was active, I used to pay taxes. Now I cannot work, but I still belong to the government. I vote. I have my voter ID. The government of Ghana owes me and my family. If there’s any way they can help us sustain our lives, they should do it.” His appeal is not just for himself, but for every leprosy survivor who has been left behind, still a citizen, still deserving of dignity and support. Mr. Adombire’s story is woven into the larger tapestry of Bongo’s leprosy survivors—a tapestry colored by pain, but also by resilience and hope. Organizations like the Development Research and Advocacy Center (DRAC) are working to ensure that people like Mr. Ayuumbeo are not forgotten. DRAC’s efforts go beyond charity; they are about rebuilding lives. With the drilling of ten boreholes, clean water is now within reach for many who once struggled. Water health committees educate communities about hygiene, crucial in the fight against neglected tropical diseases. But perhaps most remarkable is DRAC’s commitment to economic empowerment. Training sessions in basket weaving and soap-making provide patients and caregivers with skills, materials, and, most importantly, a renewed sense of purpose. “Buyers come to the community to purchase baskets, and we provide materials and training,” says Jonathan Adabre, DRAC’s Executive Director. These initiatives are more than income; they are threads of dignity, restoring connections to the community and to self-worth. Across Bongo, the story of leprosy is changing. It is no longer solely a tale of suffering, but one of resilience written in the determined footsteps of a nurse on his rounds, in the laughter of women weaving baskets, and in the hope that arrives with every borehole drilled. Yet, Mr. Ayuumbeo’s plea still rings out, a call for compassion, inclusion, and meaningful action. His journey, and that of so many others, is a reminder that the scars of leprosy go beyond the physical. It is up to all, the community, government, and organizations, to ensure these lives are lifted from the silence of stigma into the light of dignity and support. Only then will the story of Bongo’s leprosy survivors be one not just of what was lost, but of what can still be regained. WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY VIDEO Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

The Unseen Battles of Leprosy Survivors in Bongo

For ten long years, Matilda Nyaaba endured a mysterious torment. In her quiet village of Bongo Balungu, life was punctuated by fainting spells, nosebleeds, and unexplainable pain. Apexnewsgh reports Each episode left her weaker, and each visit to yet another health facility only compounded her confusion. What was this invisible enemy that drained her strength and hope, year after year? No one seemed to have an answer. Matilda’s ordeal was brought to light in the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. Her story, like those of many leprosy sufferers, was one of searching in the dark. Even as her family stood by her, her neighbors whispered, eyed her with suspicion, and kept their distance. Some said she was cursed; others assumed she had HIV. To protect herself from the sting of their words, Matilda began to retreat indoors, leaving her home only for the most essential of chores. The isolation bit deeper than the disease itself, eroding her spirit and sense of belonging. It was only after a particularly harrowing episode, a collapse so severe she was rushed to the hospital, that a turning point arrived. There, a disease control officer finally recognized the signs of leprosy and placed Matilda on a monthly treatment regimen. For the first time, hope flickered in her life. The medicine brought relief, but not certainty. Supplies at the hospital ran out from time to time, and Matilda would wait anxiously for a call or a visit, never knowing when the next dose would arrive. Still, she persevered. Her wish was simple: that no one else should have to wander in confusion or suffer in silence as she had. Matilda’s journey reveals a truth often overlooked: the wounds of leprosy are as much emotional and social as they are physical. The pain of exclusion, the silence of misunderstood suffering, and the longing for dignity weigh heavily on those afflicted. Her resilience is a quiet call for compassion, understanding, and real action, so that no one else in her community will have to endure the same lonely road. Aniah’s Journey Through Leprosy’s Trials In the village of Bongo Soe, another story of quiet resilience unfolds. Aniah Lamisi was once a farmer whose days were filled with the rhythm of the land. She took pride in the sweep of her hoe, the bounty of her harvest, and the strength of her hands. Farming gave her purpose, connection, and identity. But leprosy crept into her life without warning, first as a tingling in her fingers, then as a relentless force that twisted and weakened her hands. Tasks that once came easily, cooking, fetching water, and gathering firewood, became daily struggles. The simple act of lifting a water container to her head was now a painful ordeal. Cooking over a fire brought blisters instead of warmth. With her hands disfigured, her independence slipped away, and Aniah found herself an observer in her own life, unable to work or contribute as she once did. The loss went deeper than the physical. Though her neighbors did not reject her outright, the shame of asking for help, of reaching out with altered hands for food, wounded her pride. She withdrew from communal life, carrying her pain in silence. Like Matilda, Aniah’s only hope was regular medication—but the health center’s supplies were unreliable. Some months, she received her treatment; other times, she waited in vain, watching her health and hope falter. Each missed dose was a reminder of how fragile her world had become. Yet Aniah’s spirit refused to break. In rare quiet moments, she counted her blessings: a body that still allowed her to dress herself, fleeting moments of calm, and the knowledge that others faced even greater struggles. She dreamed of something more, a chance to learn a trade, to regain purpose, to earn her own living. Vocational training, she thought, could be a bridge back to dignity and self-respect. While Matilda and Aniah’s stories are deeply personal, they are not unique. Across Bongo and its surrounding communities, many battle the same invisible foe, facing not just disease but the crushing weight of stigma, poverty, and uncertainty. But hope comes not only from within. Organizations like the Development Research and Advocacy Center (DRAC) are changing the landscape for leprosy patients. With ten boreholes drilled in affected areas, access to clean water is no longer a dream. Water health committees teach hygiene, helping prevent further spread of neglected tropical diseases. Most transformative are DRAC’s economic empowerment programs, training in basket weaving and soap-making, providing materials, and connecting patients with buyers. For women like Aniah and Matilda, these opportunities are more than a source of income; they are a path back to belonging and pride. The story of Bongo’s leprosy survivors is one of resilience, not just suffering. It is written in Matilda’s quiet hope, in Aniah’s determination, in every basket woven and every borehole drilled. It is a story that demands not pity, but recognition and commitment. For these women and countless others, the journey continues toward healing, dignity, and a future where no one must walk alone in the shadows. WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY VIDEO; Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

A Journey of Compassion: The Unsung Heroes Battling Leprosy in Bongo

A battle is being fought, a struggle not only against disease, but against stigma, neglect, and despair. At the center of this fight is staff nurse David Asamani of the Bongo Soe Health Center, whose daily acts of compassion have transformed the lives of leprosy patients who have been forgotten by society. Apexnewsgh reports David Asamani is not just a nurse. To those he cares for, he is a lifeline, a confidant, and sometimes even family. While many health workers draw the boundaries of their duties at the clinic doors, Asamani’s responsibilities stretch far beyond. For him, the well-being of his patients does not end with the administration of medicine; it is a holistic mission that takes him across dusty roads and into the humble homes of those suffering from leprosy. The story of his devotion was brought to light during the documentary “Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience,” produced by Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen of ApexNewsGH. Asamani’s words echo the silent struggles of the people he serves: “Anytime I go to give them the medicine, I can see the suffering they are suffering,” he shares. The pain he describes is not just physical—but a deep emotional and social wound inflicted by poverty, isolation, and stigma. Many of Asamani’s patients live in the shadows, their disabilities making even the most basic tasks, cooking, cleaning, and earning a living, almost insurmountable. “Some of them will tell you they don’t even have food to eat while taking the medicine. Most of them don’t have anyone to help with household chores or economic activities; they just struggle on their own despite their disabilities.” One day, a new challenge arose. The district office called on leprosy patients to renew their health insurance and register for the government’s LEAP program. For most, this would mean a simple trip to town. But for these patients, left unsupported by family and shunned by their communities, it was an impossible journey. Asamani refused to let circumstances defeat them. “I had to use my motorbike to carry three of them to the district,” he recalls. The image is striking, a single nurse balancing duty and compassion, ferrying his patients toward a lifeline they could not reach alone. But compassion alone cannot fill empty medicine cupboards. Asamani’s dedication is tested time and again by the persistent shortages of vital drugs for leprosy and other neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). “Sometimes when patients need the medicine most, it is not available. By the time it comes, the harm has already been caused,” he laments. His plea is simple but urgent: “We will be grateful if the medicines could be available at all times. That will be very helpful.” Despite the government providing treatment for free, the reality on the ground is a different story. Attention is often focused elsewhere, and NTD patients find themselves at the bottom of the list. “Our concentration is on other diseases, neglecting these people. Meanwhile, these diseases cause a lot of economic challenges in our society. If we don’t take good care of them today, tomorrow you don’t know who might be affected,” Asamani warns, his voice carrying both frustration and hope. To Asamani, the fight against leprosy is not just medical, it is humanitarian. Each home visit, each ride on his motorbike, each moment spent listening to a patient’s worries, is a step toward restoring dignity and hope. His story is a powerful reminder that treating disease means more than dispensing drugs—it means confronting the poverty, stigma, and neglect that allow such illnesses to flourish. Yet, Asamani is not alone. The fight against leprosy in Bongo is bolstered by the work of the Development Research and Advocacy Center (DRAC), led by Executive Director Jonathan Adabre. DRAC’s approach is as holistic as Asamani’s devotion. With support from Anesved Fundación, DRAC raises awareness about the early signs of leprosy, elephantiasis, and yaws. “Many believe leprosy is genetic, but it takes up to 20 years to manifest. That misconception must end,” says Adabre. Their campaigns battle not only illness, but ignorance. DRAC’s impact is tangible. The organization has drilled ten boreholes across affected communities, ensuring access to clean and safe water. They have set up water health committees that teach hygiene practices, crucial in the fight against NTDs. But perhaps most transformative is their focus on economic empowerment. DRAC organizes training sessions in basket weaving and soap-making, providing materials and connecting patients and caregivers to markets. “Buyers come to the community to purchase baskets, and we provide materials and training,” Adabre notes. For many, these initiatives offer more than an income; they restore a sense of worth, dignity, and belonging. The story of Bongo’s leprosy patients is one of resilience, not just suffering. It is written in the determined footsteps of a nurse on his rounds, the laughter of women weaving baskets, and the hope that comes with every borehole drilled. It is a story that calls for more than sympathy; it demands action, understanding, and a commitment to never again let these lives be forgotten. WATCH THE VIDEO DOCUMENTARY: Source: Apexnewsgh.com/Ngamegbulam Chidozie Stephen

Pains of the Forgotten: Leprosy, Stigma, and Resilience in Ghana–VIDEO ATTACHED

A documentary by Ngambebulam Chidozie-Stephen (ApexNewsGH) Editor in Chief Leprosy is one of humanity’s oldest diseases, yet in 2024, it remains a pressing global health crisis. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 188 countries and territories reported a total of 172,717 new cases last year. The impact is not evenly distributed; women and girls comprised over 40% of new patients, and children accounted for more than 9,000 cases. Most troubling, over 9,100 new sufferers were diagnosed with the most severe form, grade 2 disability, a diagnosis that can mean permanent deformity and a lifetime of hardship. While leprosy’s global shadow is long, its most profound pain is felt in places like Ghana’s Upper East Region. Here, in the Bongo district, a community of just over 120,000 people, leprosy remains a silent threat. From 2019 to September 2025, 57 cases were officially reported, and the true number may be higher due to fear, stigma, and misunderstanding. Leprosy is just one of many Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) that persist in Ghana. These diseases, fourteen of which are endemic in the country, disproportionately affect the poorest, deepening cycles of poverty and exclusion. Pain Behind Closed Doors: Matilda’s Story In the tight-knit community of Bongo Balungu, Matilda Nyaaba’s life is defined not only by the disease itself but by the isolation it breeds. For ten years, Matilda endured unexplained symptoms, fainting spells, nosebleeds, and growing weakness, a mystery to both her and the health professionals she visited. “Each episode left me weaker,” Matilda shares, remembering the confusion and fear that accompanied each new symptom. The only constant in her life became her monthly trips for medicine. Her family, she explains, has been a source of support, but the wider community’s reaction has been another story. She describes a self-imposed solitude, “I advised myself to stay indoors. They would use my condition against me.” Even basic errands, like fetching water from the borehole, are shadowed by the fear of being shunned. Whispers followed her: “Some described my illness as HIV, others as a curse. This has deeply affected my mental health; I don’t know what I’m thinking anymore.” Yet, Matilda’s resilience endures. She dreams of more than just survival: “If the government could help, maybe by providing vocational training, I could regain my dignity and hope for a brighter future.” From Provider to Dependent: Ania’s Struggle Before leprosy, Aniah Lamisi was at the center of her family’s livelihood in Bongo Soe. Farming was her pride and her purpose. But illness arrived quietly, a tingling in her fingers, followed by the slow, cruel twist of her hands. Aniah’s life shrank as the disease progressed. She could no longer wield a hoe or prepare meals over an open fire without pain. Even fetching water, a lifeline in the village, became a daily ordeal. She reflects on her new reality: “Some people have lost everything, even their mental faculties. I can still care for myself, dress well, and sometimes mingle with groups. That’s how I console myself. But if I can’t farm, how do I feed myself? I just sit and eat, if there’s food. Who will work for me?” Her appeal is simple but urgent. “If the government can provide us with a vocation or manual labor, we could earn a living. Now, I just wait and hope for food. Even cooking is painful, but who else will do it for me?” In Bongo Swing, Mr. Adombire Ayuumbeo once embodied industry and self-reliance. He farmed, cut firewood, and harvested thatch, supporting his family with pride. But when leprosy struck, it took his independence, disfigured his body, and left him idle. He describes the loss with raw honesty: “Everything I used to do to earn a living is gone. Now I am helpless. I sit alone. Nobody helps me. Sometimes I think it would be better to die than live like this. People stigmatize you. I don’t know why God gave me this disease that people don’t respect. When I remembered all these things happening to me, my tears began to fall.” He issues a plea not just for himself, but for others like him: “If the government can help sustain our lives, they should do it. I vote, I have a voting ID. If the government has anything to help, we would appreciate it.” The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being, address neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) like leprosy under Target 3.3. This target states: “By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and neglected tropical diseases, and combat hepatitis, waterborne diseases, and other communicable diseases.” This means that the global community, through the United Nations and its member states, has committed to eliminating NTDs, including leprosy, as public health problems by 2030. The aim is to reduce illness, disability, stigma, and death caused by these diseases through prevention, early detection, treatment, and improved access to health services, especially for vulnerable populations. In essence, the SDGs recognize that fighting NTDs is essential for achieving universal health coverage, reducing inequalities, and promoting the well-being of all people, particularly those living in poverty and marginalized communities. Ending NTDs like leprosy not only improves health outcomes but also supports broader development goals such as education, gender equality, and economic productivity. The rising trend of leprosy in Bongo is confirmed by Mr. Bismark Kpankpari Wononuo, the district’s Disease Control Officer, who doubles as the NTDs coordinator. He explained that the numbers increase every year. He credits increased detection to community volunteers but warns that the real challenge is stigma. According to him, “Many don’t come early for treatment due to discrimination. Early detection is key; if we treat early, within nine months, it can be cured. But when affected persons decide to report late, it causes deformities to remain for life.” He further sends a clear message to the community by letting them know that Leprosy is treatable and that early detection is crucial. “Everybody is at risk.” However, he acknowledged that there are